loading

loading

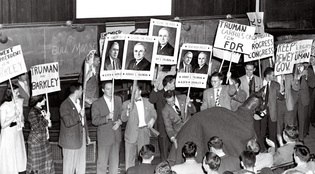

William F. Buckley: the founder Manuscripts & ArchivesA Truman rally at Yale during the 1948 presidential campaign. View full imageDuring the 1948 presidential race Yale, like other campuses, had an active contingent of students drawn to the third-party candidacy of Henry A. Wallace, who was mounting an insurgent campaign that pressed for conciliation with the Soviet Union. The complication was that Wallace's movement drew heavily on remnants of the Communist Party USA. What might this say about the handful of Wallace supporters at Yale? One answer came when a conservative professor, the political scientist Willmoore Kendall, accused a law student, in a radio debate, of effectively supporting the Soviet Union through his enthusiasm for Wallace. Kendall had been forced to retract his remarks under threat of a slander suit. "It is tragic to witness an attempt to humiliate a universally respected scholar by the use of legalistic chicanery on the part of individuals who know just when to get righteous," Buckley wrote in the News, in defense of Kendall. Sounding like a civil libertarian, Buckley warned "that in the future all political discussions must be carried out in courts of law." Consumed with the Wallace candidacy, Buckley and his debate partner (and eventual brother-in-law), L. Brent Bozell Jr. ’50, ’53LLB, assembled a dossier on the national election committee and published a lengthy expose in the News under Bozell's byline, including a list of prominent Wallace-ites with Communist associations. Not that Wallace stood any chance of becoming president. Four days before the election, Buckley and another News editor discussed the elections on "Connecticut Forum of the Air," both predicting victory for the odds-on favorite, Thomas Dewey. The next evening Buckley, Bozell, and a third member of the Yale team, Arthur Hadley ’49, thrashed a trio of Harvard debaters who affirmed a resolution endorsing Harry Truman. A News poll of 400 students, published on election eve, gave Dewey a massive victory: 63 percent, to Truman's 21. Wallace got 1 percent. Buckley listened to the election returns by radio at the Fence Club and then went over to the Yale Law School, which had a television. He watched as the late rural returns came, lifting Truman over the top, the greatest election surprise of the twentieth century. The next day he fidgeted as his economics professor, Charles Lindblom, held forth on the marvels of democracy. "After half an hour I got up and left," Buckley later said. His disillusionment assumed phantasmagoric shape in the only short story he wrote at Yale, an assignment in his Daily Themes class. "The People vs. Edgar deMilne" imagines the despair of a paragon of the Old Right, an elderly industrialist (almost identical in age to Buckley's ultra-conservative father), whose grief for his dead wife is fused inchoately with his hatred of Franklin D. Roosevelt, "the Dutchess County blueblood who always talked about the Common Man but never interested himself in anything but the vote." DeMilne stays up through the night, listening to the returns and drinking hard, first exulting and then filled with fury. At four in the morning he drains his last half glass of Scotch and collapses—slain, quite literally, by Truman's victory. Buckley later said he intended no irony in his portrait of deMilne. Yet the old man is plainly a relic, with his archaic stiff collar and stilted speech, his brusque handling of his servants, his intemperate outbursts at the Union League Club. He is, ultimately, Buckley's projection of his own possible fate: the defiant champion of rearguard actions, locked in minority positions, besting his opponents in formal debate or in the pages of the News, but doomed to larger defeats. The story's unacknowledged source text is Edwin Arlington Robinson's poem "Miniver Cheevy," whose deluded hero pines for the era of chivalry and regrets that he was born too late: "Miniver coughed, and called it fate, / And kept on drinking." Later, when Buckley needed a Skull and Bones nickname, he chose "Cheevy." His next casus belli was the accusation, published in the Harvard Crimson in June 1949, that Yale administrators were secretly purging the faculty of suspected Communists, with as many as eight FBI agents paying daily calls on provost Edgar Furniss to deliver reports on suspect faculty. Stung by the charges, President Charles Seymour ’08 assured Yale alumni that the university would "permit no hysterical witch hunt," nor "impose an oath of loyalty upon our faculty." But the rumors persisted, and when classes resumed in September, administrators quietly encouraged Buckley to challenge the Crimson's reports in the pages of the News. Typically, Buckley went further, arranging for the Bureau's assistant director, Louis B. Nichols, to appear at Yale for questioning by student and faculty "interrogators." Held in the Law School auditorium, the event drew a standing-room-only audience. Buckley, in the role of moderator, directed questions to the genial and avuncular Nichols, who assured the audience the FBI was mindful of civil liberties. But when an audience member challenged Nichols to explain why law professor Thomas Emerson ’28, ’31LLB, an outspoken critic of the House Committee on Un-American Activities and an active Wallace supporter in 1948, had been dropped from the panel, Buckley swiftly intervened. "I'll never forget this," one audience member remembered half a century later: "Bill said, 'The decision about inviting participants was made by the Yale Daily News, not the FBI.' Those were his exact words or pretty close. He was so superior, so commanding. It was all we talked about afterward. He was an impresario. We never saw anything like it." Thus the recollection of an 18-year-old law student, Robert B. Silvers ’51, who later helped found the New York Review of Books. The administration was delighted with the event. "My heart is so full of thanks and appreciation . . . for the splendid way in which your Board has met the challenge of the Harvard Crimson blast," wrote Harry B. Fisher, Yale's liaison to the FBI. It would be many years before Buckley discovered that almost every allegation in the Crimson articles was true, and that the FBI had opened a file on Buckley himself. These were some of the costs of political zeal. There were others as well. When the members of the 1950 News board convened to choose officers, Buckley feared he might be denied the chairmanship. "If I'm not elected," his sister Patricia (Tish) remembered her brother saying, "It will be a personal insult because I'm obviously qualified." In the end Buckley was elected unanimously, to his relief and surprise. Jubilant, he phoned Tish at Vassar. "I'm in! Come up!"—for the traditional celebration at the Hadden building. "I found a way there," Tish recalled much later. "He was so happy. He was on the floor, drinking so much beer and strumming the guitar, singing out of tune." The beer was an afterthought. Beforehand the new board members had chugged martinis by the pitcherful at Mory's. It was not only the prestige of the News chairmanship that Buckley craved. It was the platform it afforded, the editorial he wrote each day, the keys of his portable Royal clacking furiously as he sent forth a fresh shaft into the center of Yale's soft liberal heart. "Everyone read them, and everyone had a strong reaction," the 1950 Yale Banner would note of Buckley's provocations. "Some will always think of Bill as an arrogant, reactionary bigot. Others will always admire his courage, integrity, and sincerity." You could draw either conclusion from his frontal assault on sociologist Raymond Kennedy ’28, a very popular teacher whose course Buckley had taken as a freshman. An ardent supporter of civil rights, Kennedy had stirred the campus in 1947 with a public lecture, "Race Relations: Colonial and American," that condemned colonialism and white supremacy. But to Buckley he was a corrupter of youth whose indisputable "brilliance of oratory," along with his "bawdy and slapstick humor" had the ill-disguised purpose of making "a cult of anti-religion." Kennedy's mocking accounts of his skirmishes with religious zealots were "funny, without a doubt," Buckley granted. And Kennedy of course was entitled to his atheism. "The question," Buckley asked, "is whether this sort of business, blatantly unintellectual, biased, and unobjective, in some cases harmful, is proper business for a University lecturer." In a follow-up editorial Buckley compared Kennedy's influence over unformed student minds to the hypnotic spell "Nazi oratory" had cast over naive Germans, though of course Buckley rejected any "comparison between Mr. Kennedy and a Nazi." There was immediate protest—from faculty, students, even from Buckley's Newscolleagues, who called an emergency meeting. Buckley considered resigning but instead agreed to publish a note explaining that the Kennedy editorials, like all the others, "represent ultimately the view of one man. The responsibility is the Chairman's." But Buckley wasn't entirely alone in his views. Private letters of support came from several faculty, not to mention from grateful clergy. And Buckley's first Kennedy editorial, "For a Fair Approach" was reprinted in The Catholic World. One month into his chairmanship, Buckley had found the theme, the unacknowledged biases of liberal orthodoxy, that would inform God and Man at Yale, as well as conservative ideology for half a century to come.

|

|