loading

loading

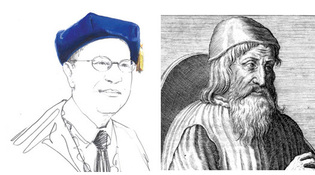

Old hat Yale hat illustration by Alan Baker; Hill Museum & Manuscript Library; Provincial Museum of Campania Capua.The mortarboard that is a staple of high school and college graduations evolved over a thousand years from ecclesiastical headgear like that worn by the fifteenth-century abbot Johannes Trithemius (above, middle). These in turn are said to have derived from the Roman pileus (above right, in a bust from the third century BCE). The Yale president's cap (above left) descends from those of the University of Amsterdam. View full imageThe square revolution: 1500–1550 From the second quarter of the sixteenth century two further types of square cap diverged from the prototype. One, which was floppier and less sharp and thin, but always four-cornered, was reserved for certain senior Oxford graduates and English bishops and secular statesmen. It was made of softer, more expensive cloth, occasionally velvet, and was more generous, form-hugging, and therefore very comfortable. Satisfactorily, it covered the ears. Holbein caught it perfectly in his incomparable portrait of Sir Thomas More. A form of it was and still is worn by certain doctors of divinity. The other form of early-sixteenth-century English square hat, plainer but still essentially four-cornered, was worn by undergraduates, choristers, and other persons of decidedly junior rank. Round versus square: 1550–1700 Square triumphant: 1675 From this date the evolution of today's mortarboard or trencher or square or college cap may be directly traced. Now usually worn with a long silk tassel hanging four inches over the edge, it is a distant but direct descendant of that leaner, squarer form of pileus quadratus allotted to junior-rank choristers. Though the seams are now absent from many polyester versions of the mortarboard, the button on top remains -- and handily, as a place to hang the tassel. The evolution of the current mortarboard has been driven chiefly by economy, such that today in America fine wool or poplin has given way to synthetic fabrics, and the brim is -- shockingly -- elasticized. One size fits all, and gone are the days when students and junior fellows went for fittings at Ede & Ravenscroft in Chancery Lane, London; or Gieves of Sidney Street, Cambridge; or Cotrell & Leonard of Albany, New York. As for President Levin's beautiful pileus rotundus, a distinctive form of headgear ex officio, it was adapted from the separate repertoire of ceremonial hats in the University of Amsterdam, for reasons that are not entirely clear to me. Perhaps -- and this is off the top of my head -- this snappy model was selected to distinguish the office of the president of Yale from that of the unreformed vice chancellors of British and other English-speaking universities. Compared with most "secular" hats, academic headgear stands as a vivid reminder that the scholarly traditions it symbolizes are exceedingly ancient and largely impervious to short-term fashion. After all, the cocked, three-cornered, or tricorn hat made of beaver skin was widely worn only for about a hundred years, roughly coinciding with the full span of the eighteenth century. It has now vanished completely, except in Hollywood and theme parks. Only the most jaded cynic would venture to describe our great university as a theme park, although its buildings and grounds are occasionally exploited to the best of their ability by Hollywood. Yet on that exciting day each May, when at commencement we reach for our hoods, gowns, bonnets, trenchers, and mortarboards, we are doing far more than putting on fancy dress: within and around each successive class of Yale graduates we are, in a meandering but unbroken historical line that extends back more than 900 years, celebrating as a living academic community the achievements of students, friends, professors, distinguished honorees, and devoted families alike -- simply by taking off our hats to them, and to each other. Long may it be so.

The comment period has expired.

|

|