loading

loading

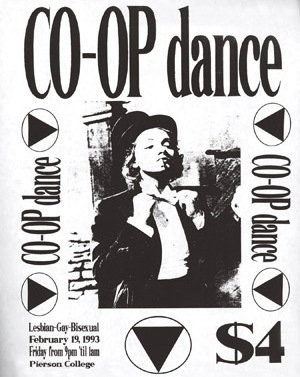

Gay at Yale Poster for a 1993 LGB dance. View full imageHow did that begin to change? In a word, the sixties. Or, really, the '70s and the '80s. The gay movement that developed in the postwar years was an "identity movement," set in motion by the relentless assertion by the state and other disciplinary authorities that sexuality provided a key to the self and that homosexuality was a disqualification from citizenship rights. From the beginning, it was shaped by the minority rights discourse and protest tactics modeled by African Americans and other groups. In the late '60s, it began to echo black nationalists' calls for black power and black pride. I've argued in my book Why Marriage? that the gay movement's insistence on breaking the old social contract with heterosexuals and renegotiating its terms -- by asserting gay people's right to live their lives openly -- was also profoundly shaped by the sexual revolution of the 1960s and '70s. All around them, lesbians, bisexuals, and gay men saw their heterosexual friends decisively rejecting the moral codes of their parents' generation, which had limited sex to marriage, and forging a new moral code that linked sex to love, pleasure, freedom, self-expression, and common consent. Heterosexuals, in other words, were becoming more like homosexuals, in ways that ultimately would make it harder for them to believe gay people were outsiders from a dangerous, immoral underworld. Moreover, the fact that so many young heterosexuals considered sexual freedom to be a vital marker of personal freedom made lesbians and gay men feel their quest for freedom was part of a larger movement. Ultimately, both gay people's mass decision to come out and heterosexuals' growing acceptance of them were encouraged by the sexual revolution and became two of its most enduring legacies. I think this did not represent the assimilation of gay life into the Normal so much as the transformation of the Normal itself. Gay organizing at Yale was born of this ferment, especially as new admissions policies made the student body more diverse, with the arrival of women and more students of color than ever before. What soon became the Gay Alliance at Yale (GAY) was made possible, in many ways, by the prior militancy of the Black Student Alliance at Yale and related groups. Black gay students, in fact, provided critical early leadership in GAY. Still, in retrospect, the goals of early organizers seem modest indeed. Activists simply wanted to create a more visible gay presence on campus, so other students would know they weren't alone, and a discussion forum. In 1969-70, just a few months after the famous riots at the Stonewall Inn in which gays and trans people fought back against a police raid, the Homosexuality Discussion Group was formed and started weekly meetings at Dwight Hall. In a sign of how quickly the terrain was changing, the group renamed itself the Gay Alliance at Yale within a year, effectively coming out as a gay organization. One of the first things gay activists worked for were courses that took their lives seriously. In spring 1973, Steve Strange '73, the new president of GAY, persuaded the Calhoun college seminar committee to sponsor a course titled "Homosexuality in Contemporary America." I was one of the 20 students who took the course that fall. It was a transformative experience to literally sit at the feet of course visitors Barbara Gittings and Frank Kameny, giants who helped launch the gay movement, and to discover that there were writers in the world who had much to teach me about the history, sociology, and culture of (homo)sexuality. Although the mostly male GAY did important work, the most dynamic political scene in those years was lesbian feminist. Lesbian feminism developed a richer institutional life and political theory than gay male politics did in the 1970s. By the end of the decade, New Haven was home to an extraordinarily vibrant and complex women's culture and lesbian feminist movement: the Feminist Union; feminist bookstores, women's health centers, self-defense classes; cooperative business ventures that sold women's music, organic food, and, yes, Birkenstocks. When the Feminist Union brought the poet Adrienne Rich to New Haven in 1980, she spoke to a standing-room-only crowd at Trinity Church on the Green. This had a powerful effect on many women at Yale, who formed Yalesbians in 1975 but often spent more time in the city's feminist bookstores and communes than on what still felt like a male-dominated and hostile campus. They brought a heightened level of political sophistication and engagement to campus discussions, and they joined other feminist students to push successfully for a Yale Women's Center and a women's studies program. Still, at the end of the 1970s gay politics and the gay social scene remained limited. It was in the 1980s that both took off at Yale. This is how I remember it -- having graduated in 1977 and returned to grad school two years later -- and I've been struck by how many alumni said the same thing to my student, Anna Wipfler '09, who wrote her senior essay on gay student organizing from the mid-'70s to mid-'80s. In 1980, the Gay Student Center began a series of gay-straight raps (that is, discussions). Later that year David Norgard '83MDiv founded the Gay and Lesbian Cooperative (Co-op), a campus-wide coordinating and political action group. It started a campaign to have sexual orientation added to Yale's nondiscrimination clause, which it won in 1986. But perhaps most importantly, in 1982 it launched GLAD (Gay and Lesbian Awareness Days), a week of lectures, films, rap sessions, and poetry readings, culminating on Saturday with a rally and dance.

|

|