loading

loading

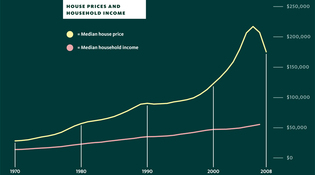

They called him “Mr. Bubble.” Mark Zurolo ’01MFAOver the long term, house price increases follow household income increases more closely than other factors. This graph shows the historical data on the housing market and household income since 1970. View full image“Whenever the public endures a crisis, ordinary citizens start to wonder how -- and whether -- our institutions really work,” Shiller wrote in the Washington Post last September, two weeks after Lehman Brothers collapsed and financial markets froze. “We no longer take things for granted. It is only then that real change becomes possible.” Shiller argues that the United States has gone through six major shifts in the way that people think about the economy: during the Revolution, during Andrew Jackson's presidency, during Abraham Lincoln's, at the end of Reconstruction, during the Great Depression, and during Ronald Reagan's presidency. These shifts were often connected to some kind of crisis. When Reagan was elected, the economy was suffering through its second severe downturn in less than a decade. Oil shocks had played a big role in those downturns, but the government deserved some blame, too. In the 1960s and ’70s, policy makers overestimated their ability to fine-tune the economy, and their mistakes helped cause stagflation. The Reagan Revolution reasserted the role of the market -- of laissez-faire economics -- in American society. But it is now clear that the revolution went too far. (True believers insist the problem was that the revolution didn't go far enough, but that's what true believers -- be they on the right or the left -- always insist.) The tax cuts of the past decade did not bring about the nirvana of economic growth that was promised. In fact, average annual growth in the current decade, even before the downturn began in late 2007, has been slower than in any decade since before World War II. And the crisis, as Greenspan himself has said, undercut the notion that individuals left to their own devices will always create a well-functioning economy. In the wake of the crisis, Shiller argues, the country is entering its seventh major shift. “We're going through a seismic change,” he said, “and our sense of support for capitalist institutions is not going to be the same.” His proposed solutions can be seen as part of a larger societal effort to recalibrate the balance between government and the market. Liberals, obviously, are happy to have this discussion. But so are some conservatives, like Richard Posner ’59, the federal judge and University of Chicago professor who recently wrote a book titled A Failure of Capitalism. Above all, this recalibration is at the heart of the current White House's agenda. President Obama has filled his economic team with market-friendly Democratic centrists -- including Austan Goolsbee ’91, ’91MA, Jeffrey Liebman ’89, Gene Sperling ’85JD, and Andrew Metrick ’89, ’89MA, a School of Management professor -- who are nonetheless trying to give the government a greater role in regulating that market. It makes sense, then, that Animal Spirits has became a “new must-read in Obamaworld,” as Michael Grunwald wrote earlier this year in Time. Peter Orszag, Obama's influential budget director (and a son of former Yale math professor Steven Orszag), has said that the book “really applies to all the big areas where we need change.” For all the radicalism of Shiller's past predictions, many of his current ideas are fundamentally conservative. He does not believe that the democratization of finance -- the rise of 401(k)s and the like -- went too far. He thinks it did not go far enough. Finance is essentially about the management of risk, he says. Investors around the world can each take a tiny slice of the risk that comes with starting a new company and, in the process, give that company far more resources than any single entrepreneur with a good idea would otherwise have. Yet many of the risks that individuals and families face cannot be managed that way. Most Americans have a huge share of their net worth in their house. They have no way to diversify this risk. Many teenagers and young adults postpone or simply avoid making the investments, like a college education, needed to pursue the career they really want. They can't quite figure out how to pay for college -- how to tap into their future income as a college graduate -- or they worry that their dream job is too risky. Shiller wants people to have the same ability to manage risk in their everyday finances that investors do with their assets. He fleshed out his ideas in a 2003 book, The New Financial Order, and he talks about them frequently. He has suggested the creation of a market for something called livelihood insurance, which would allow people to take out policies protecting them from a future decline in their income, much as fire insurance already allows them to pay small amounts of money in exchange for protection against financial calamity. Along similar lines, he wants homeowners to be able to hedge against the possibility that their home values will drop. He wants them, and other investors, to be able to “short” the housing market -- that is, to bet that prices will drop. If people don't have the ability to make such bets, he told me, “there is nothing to stop bubbles created by zealots, even if the smart money knows they are bubbles.”

|

|