loading

loading

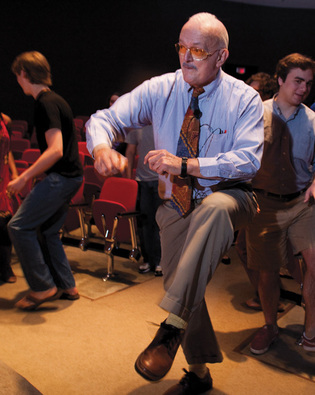

Professor of mambo Mark OstowMaster T dancing at a meeting of his undergraduate course this spring, The Black Atlantic Visual Tradition. View full imageIt’s Fall 2009, and 150 musicians, dancers, professors, and former Thompson graduate students have crowded into an auditorium at Boys Harbor in Spanish Harlem. Two New York City cultural centers have put together a tribute to Thompson called “Que Rico Mambo! Que Rico Robert Farris Thompson!” From the amplifiers sound the opening drumbeats of “Mambo en Sax,” by the Cuban-born mambo popularizer Pérez Prado. Thompson takes the microphone to give a tour of the piece. “The trumpet is building some sort of staircase, some sort of ecstatic staircase, and it will be picked up and change mambo forever.” Now Thompson tells the audience to listen for “a little bit of Schoenberg,” a subtle dissonance “like heat lightning in Jersey being observed from Manhattan. Pérez Prado did the impossible. He made dissonance popular. He put it into a groove.” Next, another Pérez Prado recording, “Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White.” As the trumpeter sustains a note, Thompson calls out: “How long can you hold it, brother? How long can you hold it? Hold it, hold it, hold it in the name of God!” Thompson as lecturer is “kind of like Jack Kerouac crossed with John Coltrane,” says screenwriter David Martino ’85. “It’s an improvisation.” New York City musician and journalist Greg Tate calls Thompson “an academic jazz musician”: “Jazz musicians know music backward and forward, but they’re completely unself-conscious in performance. When you’re on the bandstand, you want to connect, communicate, make it hot.” Furthermore, says Tate, “It’s completely consistent with the tradition he’s trying to represent. African culture is very performative.” Thompson himself says that when he lectures, “I am not lecturing. I am being lectured by the forces on the screen.” During a single 50-minute class, Thompson speaks Spanish, Yoruba, French, Hebrew, Creole, Portuguese, and Ted Kennedy. He signals a row of students to stand up and try a dance step. He approaches a young man and demonstrates a gesture of self-protection found in sculptures from West Africa: arms crossed on the chest, hands on opposite collarbones. A similar gesture appears in an early-nineteenth-century drawing from Suriname. What links them is that whether in Africa or the New World, the gesture conveys the same message: “I’m not going to let you provoke me! You don’t exist. Boom!” Much of Thompson’s research has been in learning and tracing the language of gesture. During a conversation in the master’s house at Timothy Dwight, he stands, leans onto the balls of his feet with knees bent, and flaps his knees in and out. “If you find in Kongo a guy waving his thighs like this in front of a woman, and you hear a song—‘Hey, pretty mama, I’m bewitched by your body, hey pretty mama, I’m willing, I’m willing’—it may go with this gesture. This gesture has a specific name, vwendama. Well, that gesture—suddenly we see it in paintings of Kongo societies in Uruguay. Suddenly we see it in a 1952 photo from the Palladium [a dance hall in midtown Manhattan]. Suddenly we see it on the floor of the Savoy Ballroom [of Harlem] in 1954. Again and again. It’s this frequency of occurrence that tells us how important it is. But also, it has similar meanings: it’s a flirtation step. So my method is comparative.” When Thompson finds related patterns with overlapping meanings and similar contexts, “that’s when we know we’ve hit pay dirt.” Another example: Thompson puts his hands on his hips. “In the white world,” he says, this stance is “a throwaway line. But in the black world, it’s a sign of arrogance. When it’s black, it’s associated with sassing. People say, ‘Oh, but this is universal.’ Yeah, anyone can stand arms akimbo, but what does it mean? When I lecture, I ask someone in the audience who’s black—and I stand like this—‘If you were my grandmother, what would you do?’ ‘I’d whip your ass to okra.’ That’s how strong it is.”

|

|