loading

loading

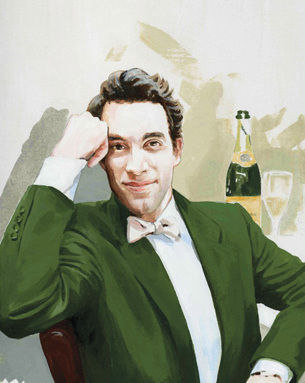

featuresTo an aesthete dying youngA National Book Award–winning writer pays tribute to a Yale roommate who killed himself last year. Andrew Solomon ’85 is the author of three books, including The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression, which won the 2001 National Book Award.  Illustration: Josie JammettThis portrait of Terry Kirk ’84 was commissioned after his death and was based on a photograph. View full image

I sometimes hold it half a sin

In February 1982, in the middle of my freshman year, I was invited to a party by the most glamorous sophomore I had ever met (now one of my closest friends), and I was wildly excited about it. It was in that perfect proportion for a social event: a third of the people were people I actually knew; a third were people I had seen around and wished I knew; a third were people I had never seen because they inhabited a stratosphere too exalted to have been visible to me, some of them even juniors and seniors. The party was in a dorm room in Pierson. Spandau Ballet, Pat Benatar, the Human League singing “Don’t You Want Me Baby,” which nowadays feel to me as sweetly nostalgic as “Dixie,” were at that time fresh as the morning dew. People were dressed in clothing that might in 2010 be coming back into fashion for the fifth time, but that was then just coming into fashion for the first time—even though much of it had been cleverly selected at the Salvation Army. In those days, the drinking age was still 18, and so there were drinks, and there were some people doing cocaine in the bathroom, because it was, after all, the 1980s. I would not have been more thrilled and dazzled to have been invited to the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer one year earlier. People were witty and funny, having a truly good time, dancing well, laughing. Some were sitting around in the disco half-light of the room itself, others in the glaring fluorescence of the stairway, and some in little knots in the moon-drenched courtyard. I had hated high school and had always felt marginal there, and now here I was with all these amazing people, and I was having one of the best times of my life. It’s hard to remember the full cast of that party, but I tried it as an exercise recently and realized that I am still good friends with more than 20 of the people who were there, and am Facebook friends with at least another 25. I always say that Yale was the beginning of the self that I have been ever since, that I was someone else in elementary and high school, someone I barely remember, but that at Yale, I started to be me, and that party has always stuck in my mind as the moment when the shift became official.

A theatrical-looking man was holding court in one of the rooms of the suite, someone who had been pointed out to me as the roommate of Jodie Foster’s boyfriend, and he and I got into a long conversation, and if that party felt like the center of the universe to me at the time, he seemed to be at the center of that center; everyone came over to talk to him, and he kissed and hugged with real affection all the spikiest people there; he introduced me to everyone I didn’t already know, taking me under his wing. I was flattered by the attention, and a little bit mystified by it, and I settled in and we talked for much of the evening. When I grudgingly decided I should leave the party at 3 a.m. lest I look too eager, he said to me, “Would you like to be roommates next year?” Startled, I impulsively said yes, then said we should talk about it more, then said yes again, and left. I got back to my room in Bingham Hall with visions of sugarplums dancing in my head. The next day, I mentioned, casually, to several people that I was thinking I might have Terry Kirk as my roommate the following year. Some seemed rather awestruck, and some were rather cynical, and some asked if I were really up for all that. I wasn’t sure about anything; I wasn’t even sure if Terry had meant it. I wasn’t sure that I as a freshman could room with a current sophomore the next year. But two days later, I ran into Terry on Cross Campus, and he said, “Well, well, well! Are we going to room together?” And I said yes with the same feeling with which, later on, I would deal with love and adventure and travel and life, that feeling of looking both ways, deciding it was dangerous, and leaping anyway. There was a warmth in Terry, and a twinkle, and an exuberance, and all those qualities made the glamour a little less terrifying than it might otherwise have been. Many years later, when we talked about that time, Terry said that he didn’t want to room with anyone he might sleep with—which I later realized cancelled out a sizeable chunk of the undergraduate population—and that he liked me more than anyone else he’d been not physically attracted to. I spent some time trying to decide whether this was a compliment, but I think it was true and mutual. I was hideously repressed at the time and mostly unwilling to acknowledge a physical attraction to anyone, but I was not attracted to Terry, even though he was handsome and shiny. I kept sexual and romantic attraction very separate then, and nothing suited me better than a completely unerotic but deeply romantic friendship, and that is what we had. I wanted to be wild and outré, but I was constrained by a deeply ingrained respect for decorum, something that now looks to me like a straightjacket. There was nothing Terry could imagine doing that he wouldn’t actually do, and this terrified and thrilled me. He generally wore a green Austrian loden cape, and a mad hat with a feather in it. He played the leads in musicals and danced just the same way on stage and off—even while waiting in line for brunch in Davenport. He usually had a boyfriend and a girlfriend going, sometimes more than one of each, and he wasn’t sexually exclusive even within those loose confines. He was interested in everything and everyone; I learned from him that categories were idiotic, that there was fun to be had everywhere. He had absolutely no money, but he inexplicably seemed always to have a bottle of Veuve Clicquot champagne to hand. In 1982, Veuve Clicquot was not widely marketed in the United States, so it would have been novel across America, but at Yale it was absurd; the rest of everyone drank Freixenet if they were too pretentious for beer. It’s hard in some ways for me to recall all of what made Terry so riveting, because he taught so much of what was amazing about himself to me, and now that his influence is woven into my personality, I can’t tease it loose again. I don’t remember the person I was before I absorbed his glitter and his belief that life was a quick exercise in pleasure.

Spring break, freshman year, I panicked. I did not want to be gay; I was not going to be gay. If I roomed with Terry Kirk, people would think I was gay. If I roomed with Terry Kirk, there would be wild parties in my own room, and I would never be the faux WASP prepster I had planned to be. I knew that histrionic people were fake, and that real people were restrained and moderate and focused on their grades. I would fail if this went ahead. My parents had asked me about the person I was going to room with, and I had decided that since both Terry and my father were great opera buffs, it would be a good idea to invite Terry to come and see Madame Butterfly with my family. We were to meet at my parents’ apartment and have drinks, then go to dinner at my mother’s favorite restaurant, and then proceed to the Met for the performance. Terry arrived a half hour late, which was not an acceptable opening gambit in my family under the best of circumstances. He showed up, also, in the green cape and the hat, wearing white pants tucked into knee-high boots from Charles Jourdan that had most likely not been intended for men. He cut what might euphemistically have been called a dashing figure. My mother was seething already about the delay, and I watched with a churning stomach as Terry turned on a flow of charm that simply refused to wither under her withering glare. Now that I’m old and wise, I can see that my mother, too, thought that I must be gay if I were going to room with Terry Kirk, and she wasn’t very happy about it, but at the time, I just remember being relieved when what struck me as the comparatively happy and untheatrical story of Cio-Cio San began to unfold on the stage.

|

|