loading

loading

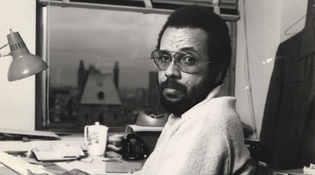

featuresBefore their timeThe 1960s saw the first significant presence of black men in Yale College. Forty years later, a disproportionate number have died. Did the racial barriers they faced all their lives play a part? Ron Howell '70 is a reporter and a journalism professor at Brooklyn College. He is writing a book about black immigrants in early-1900s Brooklyn.  Courtesy Monica MurphyCivil rights attorney Clyde Murphy ’70, shown here in his office around 1980, died of a pulmonary embolism last August at age 62. Nine of the 32 African American men who entered Yale in the Class of 1970 have died, a rate more than three times that of the class as a whole. View full imageIn three decades as a news reporter, I've seen hundreds of bullet-riddled bodies in Haiti and in the Middle East, and I've had friends and colleagues killed in both of those places. I lost my father to cancer. But no death transformed me like the death last August of Clyde E. Murphy, my buddy from the Class of '70, my brother in Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, the best man at my wedding as I was at his. Clyde was the confidant with whom I shared deeply held feelings about life and death and—perhaps most of all—about being a black man in America. Then, six months later, as I was making peace with the sudden loss of Clyde to a pulmonary embolism, word came that yet another brother who'd pledged Alpha with us, Ron Norwood '70, had succumbed to cancer. A few weeks after that we learned that Jeff Palmer '70, another black classmate, had passed, also from cancer. Truth be told, over the years I have from time to time floated the idea that some racist scientist had slipped poison into our milk, after our births or while we were at Yale. Others, not easily inclined to conspiracy theories, have also puzzled at what seemed to be a disproportionately high death rate for black Yalies. "For ten years or more, I have been commenting on the excessively high mortality in that cohort of male black students at Yale who matriculated there between '64 and '70," wrote Charles S. Finch III '70, an Atlanta-based emergency room physician who was a close friend and Alpha brother to Clyde and me, in an e-mail to a list of black alums. "I think there may be 24 (or more) such men, none of whom got past age 62, most not even seeing their 60th year. It is astonishing and disturbing." I began pondering this issue of black mortality with increased energy and fervor last summer, after my wife Marilyn and I drove up from Brooklyn to New Haven for the last day of my class's 40th reunion. I had a wonderful time, reminiscing and sharing with guys I had not seen in decades and others I did not know at all. But there was a sobering side. The computer sitting outside the registration room was open to a necrology for our class. It was haunting. I scrolled up and down it, stopping at one remembered Afro-headed Yalie and another. There was a total of about 80 names on the list, more than half a dozen the names of black men, as I recall. We African Americans back then numbered only 32, out of a class of just over a thousand. (This number doesn't include the five black men from Africa and the Caribbean, who faced different kinds of challenges.) There surged in me again, momentarily, a sense of death clouds hovering above our heads. But the moment passed. We went outside, Marilyn and I, and sat under the convivial tent offering protection from elements and petty worries, happy with life. We ate and danced to the music of Plastic Visitation, whose singer Ralph Dawson '71 revived in us the Motown energies that once made us so cool. We headed back to Brooklyn, and over the next couple of days I exchanged e-mails—happy, reflective e-mails—about my reconnections to the past.

|

|