loading

loading

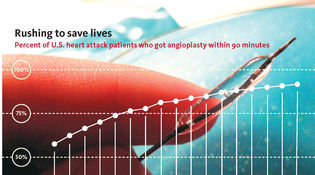

The heart of the matter Chart: Mark Zurolo ’01MFA. Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Photo: Denise Chan.Heart attack patients should receive angioplasty—a procedure that clears arteries using a catheter and a balloon—within 90 minutes of arriving at a hospital. In 2006, Krumholz and the American College of Cardiology launched a national campaign that has radically improved hospitals' speed. View full image“The tension in an academic institution is, how are you branding yourself?” he says. “What’s your shtick?” Though he doesn’t put it this way, Krumholz does have a brand. Instead of diagnosing a specific disease, he’s diagnosing the American health care system. “Harlan’s work is fundamental to the quality of care,” says Jerome Kassirer, a former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine and professor at Tufts School of Medicine. “He put outcomes research on the map.” Now that map is about to get a lot bigger. Last year’s federal health reform law created a nonprofit organization called the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, or PCORI. Charged with conducting research on what treatments work and don’t work for different patients, PCORI will give away more than three billion research dollars in the next decade. As a member of the group’s board of governors, Krumholz will play a leading role in deciding where and how to spend that money. And what about the “patient-centered” part of PCORI? After watching Krumholz perform the trans-esophageal echocardiogram, I ask what it has to do with the rest of his work. “It keeps reminding me that we’re dealing with individuals who are scared and uncertain,” he says. “They can’t tell, are you a good doctor or a bad doctor. What they can tell is: are you kind? Are you listening?”

Lesson 4: no teacher like success The faster you treat a heart attack, the better the patient’s chances. Doctors have known that since at least the mid-1990s. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend that hospitals perform angioplasty, a procedure that clears blocked arteries using a catheter and a balloon, within 90 minutes of a patient’s arrival. Yet in the mid-’90s, the average “door-to-balloon” time was about two hours. By 2005, hospitals still missed the 90-minute target half the time. “Everyone thought it was impossible to consistently get below 90 minutes,” Krumholz recalls. But on closer inspection, he and his colleagues found “a small number of hospitals treating people with extraordinary speed.” Teaming with Elizabeth Bradley ’96PhD, a Yale professor of public health and director of Yale’s Global Health Leadership Institute, Krumholz contacted the top performers to plumb their secrets. “None of them were surprised when we called them,” he says. “They all said, ‘Oh, yeah, we’re good at this.’ It wasn’t by accident.” The researchers interviewed key players and distilled their speed strategies. (One key move, according to Bradley: let the ER docs diagnose a heart attack instead of waiting for a cardiologist.) They published the results in 2006 in the augustNew England Journal of Medicine. “For a lot of academics that would have been enough; they’d stop right there,” notes Ralph Brindis, immediate past president of the American College of Cardiology. “But, social scientist that he is,” Krumholz wanted to translate the collected wisdom into action. With the ACC, in 2006 he launched the D2B Alliance, a national campaign to reduce door-to-balloon time. (At one point they consulted a NASCAR pit-stop expert for tips on shaving minutes or seconds off routine operations.) Within its first year, the alliance had enrolled 1,000 of the roughly 1,400 U.S. hospitals that perform angioplasty, and in 2008 it met its initial goal: 90 minutes from door to balloon for 75 percent of patients at the participating hospitals. The alliance continues to expand, says Krumholz, and reports D2B times as short as a half-hour. “That represents lives saved in the nation,” Brindis says, “and I would give Harlan the lion’s share of credit.” Bradley says that when she worked as a hospital administrator before coming to Yale, physicians considered talk of health care quality “a bureaucratic, administrative, financial thing,” something “adversarial” imposed by bean counters. Krumholz reframed quality problems “as opportunities for improvement—focusing on solutions and progress, not problems with past performance,” she says. “So they saw outcomes not as, ‘Someone’s going to measure my numbers and slap me,’ but ‘This is what medicine is all about. More patients are going to live.’”

|

|