loading

loading

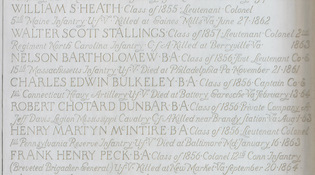

"The mingled dust of both armies" Christopher GardnerAlumni who died in the war are listed chronologically by class year; Union ("USA" or "USV") and Confederate ("CSA") soldiers are intermingled. View full imageFrom the start, the memorial planning committee sought to appease Southern sensitivities. The committee originally adopted the South’s preferred appellation for the conflict, “the war between the states.” “The phrase ‘War of the Rebellion’ is in many ways accurate,” wrote Anson Phelps Stokes ’96, the University Secretary and a member of the planning committee, “but it is so distasteful to our Southern friends that it is out of the question.” Stokes suggested that “civil war” would be the most “unobjectionable,” and that was the title finally settled on. Seeing the memorial as an aid to reconciliation, the committee was adamant that the memorial be centrally located. They agreed that the memorial should be “seen daily by the students” and “catch the eye of visitors.” The original 1865 proposal had called for a memorial chapel, but the committee settled on the corridor in the new “bicentennial buildings”—Commons, Woolsey Hall, and Memorial Hall—which had been constructed to commemorate Yale’s 200th anniversary in 1901. The committee debated for months over how to list the Confederate names and struggled to think of ways to obscure Yale’s overwhelmingly Union affiliation. In the end, the 114 Union dead and 54 Confederate dead were intermingled, listed together chronologically by class year. One point of disagreement, ultimately settled in the Southerners’ favor, was whether to include the Confederate soldiers’ military ranks and titles. To committee member William Gordon, the question was a simple one: “The soldiers of the South … believed in their cause and died in defense of the faith that was in them. If this fact is to be ignored, their names upon a Yale memorial will be a mockery—if not an insult.” Yale’s memorial must not only list the Confederate dead, but also pay tribute to their military service. (Seven years later, Princeton, which had nearly equal numbers of Union and Confederate dead, dedicated a memorial that listed only the names of the fallen, without indicating the side on which they had fought.) Yet the cause for which that service was rendered had to remain unspecified. As Gordon put it, the idea behind including Yale men from the North and South was to “embody and recognize the fact that each was true to his principles and each deserved equal tribute of praise and that Yale University wished to proclaim this fact to the world, that the mingled dust of both armies created a solid foundation for the future of the nation.” Therefore the memorial should note simply that each man died for what he believed in, Gordon argued, and keep silent on the content of those beliefs: “Anything intended or capable of being construed into recognition or endorsement of either Federal or Confederate beliefs will destroy the keynote of the whole affair.” These arguments prevailed in the committee. The memorial includes no mention of slavery or emancipation; its dedication expresses only the hopes that the soldiers’ “high devotion” may live in all of Yale’s students, and that “the bonds which now unite the land may endure.” At a university whose motto is “Light and Truth,” the memorial shrouds the causes of the great war in darkness, giving way to the national determination to forget. But forgetting can be dangerous. “I am not indifferent to the claims of a general forgetfulness,” said Frederick Douglass in 1894, “but whatever else I may forget, I shall never forget the difference between those who fought for liberty and those who fought for slavery; between those who fought to save the Republic and those who fought to destroy it.” As he watched the two sides “shaking hands over the bloody chasm,” he despaired: “If this war is to be forgotten, I ask in the name of all things sacred what shall men remember?” Douglass’s fears have, in some sense, come true. Today, 150 years after the start of the war, the nation continues to argue about its causes. Even as Yale’s memorial aided the spirit of reconciliation that was necessary for the country to move forward, it likewise promoted the tendency to forgetfulness that makes today’s political battles more contentious, that insists that both sides were righteous, that overlooks the central role played by the question of human bondage. Indeed, the memorial itself—at least as a specific tribute to the Civil War—is largely forgotten; its anodyne character allowed the university to subsequently expand it by adding the names of Yale dead from every war America has fought, including the Revolution. The inscriptions the committee argued over for years have been worn down to near-illegibility, and they are often hidden altogether by floor mats. David Blight could have been writing about Yale’s own monument when he described the move toward national reconciliation as above all else “a story of how in American culture romance triumphed over reality, sentimental remembrance won over ideological memory.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|