loading

loading

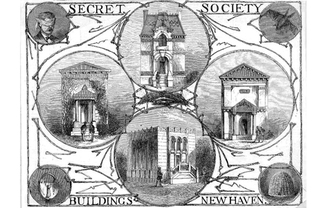

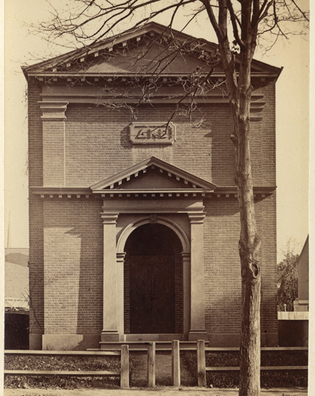

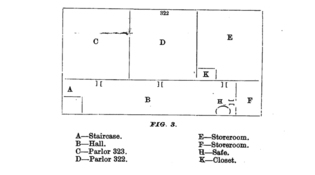

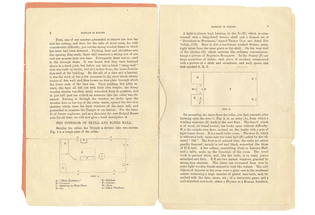

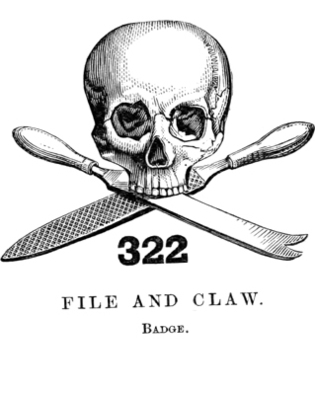

featuresThe origins of the tombHow Skull and Bones found a home. David A. Richards ’67, ’72JD, is writing a history of college societies in the United States. Editors’ note: Richards’s name is included in the list of Skull and Bones members in the graduation book of the Yale College Class of 1967. However, this article draws entirely on publicly available sources.  Library of CongressThe Skull and Bones building, the oldest US fraternity house still standing, is shown here in the early twentieth century, with the entrance and right-hand block that were added in 1903. View full image The New Haven MuseumThe Skull and Bones tomb as it appeared in its original configuration, with just one rectangular, windowless block. View full imageIn nineteenth-century America, college fraternities were called “secret societies,” and they met in windowless buildings constructed for the purpose. The first fraternity house built in the United States was a log cabin erected in 1855 by Delta Kappa Epsilon at Kenyon College in Ohio. But the oldest fraternity house still standing is the Skull and Bones tomb in New Haven, on High Street near the corner of Chapel. “Tomb” was the name it attracted when it was built in 1856, and a tomb is what it resembled, even more so than in its current remodeled state. It was a single forbidding, windowless block in Egypto-Doric style. The society had been founded in 1832. The conception seems to have been that of the 1833 valedictorian, class orator, and secretary of Phi Beta Kappa, William Huntington Russell. He was joined as a founder by Alphonso Taft, future father of US president William Howard Taft, Class of 1878. (Alphonso, his son William Howard noted in a speech given at Yale in 1909, had been so determined on a quality college education that he “walked from Vermont to Amherst College, Mass, and then he heard there was a larger college at New Haven, and he walked there.”) Russell, Taft, and their four cofounders were all Phi Beta Kappa. They invited eight classmates to join them. They seem to have made a deliberate attempt at diversity; the eight included the only two members of the Class of 1833 from the Western states (Ohio and Illinois), and also two of the class’s seven members hailing from Southern states. The society was known to its members as the Eulogian Club: eulogia is Greek for “a blessing” and is applied in ecclesiastical usage to the object blessed. The name Skull and Bones came about almost by accident, when one of its members in that first year posted a meeting notice in the usual place for undergraduate announcements—Yale’s chapel door—and, as he wrote later, impetuously “sketched over the notice a Skull & Cross-bones… simply to attract attention and make a sensation among outsiders! Which it did very decidedly.”  Manuscripts & ArchivesA black wax seal, circa 1865, with the Skull and Bones emblem. View full image Manuscripts & ArchivesA late-nineteenth-century engraving showing the halls of Psi Upsilon (top), Skull and Bones (left), DKE (right), and Scroll and Key. View full imageThe symbol quickly generated a name for the society on campus and was adopted for the group’s badge—a skull and crossbones over the number 322. Why 322? There are many theories, the most often cited being that 322 BCE was the year on or near to which Alexander or Demosthenes died. There was an adopted language as well. Graduate members are “patriarchs” and initiates “knights,” and all meet in a “temple.” And, again following the ancient Greeks, society members called outsiders “barbarians.” The society was almost immediately offensive to the faculty. The professors met on Christmas Day of 1833 to determine the punishment for antics at a “convivial meeting” of Bones. Nine members of the Bones club of 1834, including a future Yale treasurer, a future US congressman, and a future associate justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court, received warnings with letters sent to their parents. Two of the club who had not yet been formally admitted as members of the senior class were advised they would not be admitted at all—although in time the faculty relented, and the two graduated with their class. An 1872 memoir tells the story that, at another time, “the faculty once broke in upon one of [the society’s] meetings, and from what they saw, determined upon its abolishment, but by the intercessions and explanations of its founder [Russell] then serving as a tutor among them, were inclined to spare it.” Indeed, Bones took root so firmly that in 1842, when it was just a decade old, a member of the Class of 1844 wrote in touching ignorance: “The Skull and Bones Society is of quite an ancient origin. It is one of the most secret associations” in the college. In the early years society members met in rented rooms in commercial buildings in town. This access to outside space was regarded as one of the chief satisfactions of membership, due no doubt to the state of the undergraduate rooms at Yale College. The Old Brick Row dormitories, on the site of the Old Campus, had sagging, low ceilings, billowy floors, cracked walls, and a musty odor. The heat from the coal stoves varied with the fuel supply, and tallow candles and whale-oil lamps fouled the air. (Professor Benjamin Silliman, Class of 1796, is reputed to have said that he would not have stabled his favorite horse in such accommodations.) By comparison, even the relatively humble rooms rented by Bones must have seemed a haven. But in 1856, the Skull and Bones alumni acted decisively to give society members an entirely different meeting place. Scroll and Key, established after Bones, had long been meeting in a custom-designed penthouse suite in a New Haven office building, and its members regularly mocked the quality of the Bones quarters—also in an office building, but merely a low-studded back room on the third floor. Moreover, many of the Bones alumni lived in New Haven, and as the group’s elders, they now had over two decades’ worth of reputation to protect and memorabilia to preserve. They were well aware that, in any annual election gone wrong or during a fractious year, the club might simply implode and disappear, as other senior societies had done. They wanted to make Skull and Bones a permanent institution. The first step was to incorporate the club in the State of Connecticut as a trust; they called it the Russell Trust Association. Now, a proper corporation could hold fee-simple title to the remarkable structure that announced, if any were in doubt, that Skull and Bones was here to stay. The new building caused a campus sensation. Though its interior features were generally unknown (yet), from its outer facing the new home of Bones seemed large and sumptuous. Its cost was later estimated at about $30,000; the cost of Yale’s own first stone building in 1842—the Old Library, now known as Dwight Hall—had been less.  Library of CongressThe 1884 Wolf's Head building is now part of the university. View full image Library of CongressThe Scroll and Key hall, shown here in about 1901, was widely admired for its Moorish Revival style. View full image Manuscripts & ArchivesDelta Kappa Epsilon's hall was the first imitator of the Skull and Bones tomb; it was torn down to make way for Branford and Saybrook Colleges. View full imageWhen first built, then, the structure was less than half the size of its current configuration. It consisted of what is now the left-hand block, with a doorway in the center (where there is now a slotted window). Its aspect was forbidding. The sandstone blocks were darker than the surrounding buildings. There were no windows to be seen. The massive, close-fitting doors were of iron, 12 feet high, upon which the society emblems were displayed. The roof, nearly flat, was covered with plates of tin. (Later, it would be plates of iron half an inch thick.) The skylight was similarly protected, with the chimneys and ventilators ranged around the edge of the roof. In the rear, a pair of small blind windows were barred with iron. Below, at the foundation level, were scuttle holes—openings into the cellar—which were also barred. The architect was Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–92) (though many have suggested Henry Austin, 1804–91, who was responsible for the architecturally similar gates of the Grove Street Cemetery). The structure would be enlarged in 1883, when a second block was added onto the rear; and again in 1903, when the original block was faithfully duplicated to the east and a new entrance placed between the two blocks. From the time the club took up occupancy on March 13, 1856, the tomb became a campus focal point. It inspired new rituals for the society’s members and new habits for the nonmembers (“neutrals”). Its features—such as the beveled sandstone pylons along the street frontage and the padlocks on the doors—figured in the letters (burned at the edges and sealed with stamped black wax) that invited neophyte members to the tomb: “Pass through the sacred pillars of Hercules and approach the Temple. Take the right Book in your left hand.…” Would-be intruders discovered that if the wrong padlock was pulled, or the right one twisted the wrong way, a warning bell was set off inside. Members to this day are discouraged from entering or leaving the building before witnesses. If observers are unavoidably present, those same members refrain from making eye contact, and enter in quick single file, silently. Bonesmen also refused to speak when passing in front of their building. Very soon, casual pedestrians with knowledge of the tomb’s identity would cross to the far side of the street before passing it. “The society halls,” a commentator of the 1890s would observe, “are retired and guard their own secrets. Curiosity stops abruptly at the iron doors.”  Manuscripts & ArchivesIn 1876, a group of undergraduates calling themselves "the Order of the File and Claw" broke into the original Skull and Bones tomb—and published a pamphlet about it. Above is File and Claw's sketch of the second-floor plan. View full image Manuscripts & ArchivesPamphlet pages showing floor plans for the cellar and the first floor. View full imageThe only public record of the original 1856 hall of Skull and Bones is a pamphlet entitled “Babylon Is Fallen,” published in 1876 by a group calling itself the “Order of the File and Claw.” These self-styled “neutrals [with] the vulgar eyes of the uninitiated” broke into the tomb in September of that year by defeating the iron netting and the two rows of iron bars on the back-cellar windows. First, they spent “many hours of patient and cautious labor” filing through one of the outside bars, and used a “powerful claw” to draw out the long nails that fastened the netting to a wooden frame. Then they put the bar back in place with putty and “retired to await a favorable night for finishing the job.” At 8:00 on the evening of September 29, they came back. They pulled out the wooden frame and found that the inside window bars, at the bottom, ran down into a brick wall. They dug through this wall with a hatchet and loosened the iron plate to which the bars were attached—and when they pushed the plate inward, the bars fell out of their own accord. At 10:30, the intruders were inside. They “proceeded to examine the Temple at our leisure.” The cellar had a kitchen, pantry, sink, and “Jo” (toilet), where “a light is always kept burning” and which was “ornamented with a dilapidated human skull.” The main hall on the first floor, “called by the initiated ‘324,’” had “gaudily frescoed” walls. The only objects of interest in 324—at this date in 1876, at least—were a used textbook and a glass case “containing a large number of gilded base-balls, each inscribed with the date, score, etc., of a university game.” The invaders were disappointed, because “thus far we had found little to compensate us for our trouble.”  Manuscripts & ArchivesThe emblem File and Claw printed on the front of the pamphlet—an adulterated version of the Skull and Bones emblem. View full imageAscending to the second floor, they found three parlors, one containing the library and full of interesting information about other societies. (Next to the name of one Scroll and Key member was “written, in a bold hand, the mystic symbol “Ass.”) The middle room, numbered “322,” was the sanctum sanctorum. It included a “life-size fac simile of the Bones pin, handsomely inlaid in the black marble hearth” of a fireplace. Just below the mantel was a motto also inlaid in marble: “Rari Quippe Boni” (“The good are indeed few”). Along the walls of the hallway were some 40 years’ worth of group photographs. File and Claw also rifled the society’s safe, discovering nothing but “a bunch of keys and a small gold-mounted flask half-filled with brandy.” Other miscellany included “a set of handsome memorabil [sic] books, one for each year,” and two general storerooms filled with boating flags and foreign-language books. The authors found, they noted, “a total absence of all the ‘machinery’ which we had been led to expect.” Their conclusion: “Thorough examination of every part of the Temple leads us to the conclusion that ‘the most powerful of college societies’ is nothing more than a convivial club.” They could see, in other words, only what they could view, so the society’s true secrets remained safe. With the tomb, Skull and Bones had become the first “landed” senior society, indeed the first fraternity of any sort to have its own freestanding building at Yale. The tomb would have many followers: first Delta Kappa Epsilon, with a windowless, two-story, red brick building in 1861; later Scroll and Key, with the nationally admired Moorish Revival–style structure that still stands at Wall and College. More came later: Wolf’s Head’s (first) tomb at Trumbull and Prospect Streets in 1883; Book and Snake’s hall at Grove and High in 1901; and Berzelius’s tomb at the Whitney-Trumbull-Temple intersection in 1911. As an early DKE history puts it: “The old ‘Tomb’ at Yale with its windowless walls, its forbidding exterior, and its mystic symbols has raised the hopes and desires of many an undergraduate.”

|

|

3 comments

-

Randy Alfred, 12:22am May 12 2015 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Grant Burnyeat, 11:19am May 27 2015 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Mark A. O'Blazney, 7:23am August 01 2015 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.What cost $30,000 in 1856 would cost approx. $779,000 today. See "The Inflation Calculator" at http://www.westegg.com/inflation/

I am the Chair of the Archives and History Committee of DKE. I would be most interested in helping with your project and receiving a copy of what you produce.

"……… and its mystic symbols have raised the hopes and desires of many an undergraduate."

I see The Grateful Dead appreciated these "mystic symbols"……. right, Mr. Gore ?? Happy birthday, Jerry.