loading

loading

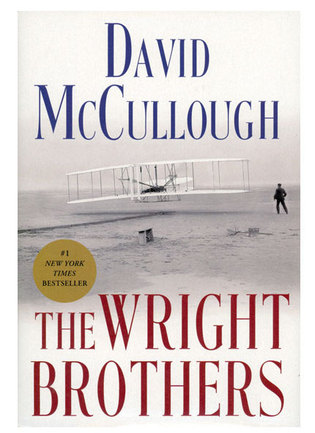

Reviews: November/December 2015 View full imageThe Wright Brothers Alex Beam ’75 writes for the Boston Globe and is working on a book about Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson. Yes, you knew that they were bicycle mechanics from Dayton, Ohio. But it is unlikely you knew that neither one of them attended college (although Wilbur dreamed of going to Yale). You may not have known that Orville survived a catastrophic 1908 crash that killed his passenger, and then survived all four of his siblings, dying in 1948 at age 76. I certainly didn’t know that three full years after their pioneering flights in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the press in aviation-crazed France was denouncing the Wrights as frauds and “liars.” It wasn’t until the public trials at Le Mans in the summer of 1908—now five years after Kitty Hawk—that the civilized world, meaning Europe, saw the miracle itself: Wilbur flying over two miles of French countryside, lazily executing perfect turns in the gathering dusk. French aviation pioneer Louis Blériot, who would soon become the first to fly the English Channel, gave voice to the collective awe: “C’est merveilleux!” The brothers’ saga is spellbinding, and McCullough has the wisdom to let the reader think the tale is telling itself. He shows us, for instance, a man flying 984 feet above New York Harbor, circling the Statue of Liberty in a handmade biplane equipped with no safety features whatsoever. The Wright brothers matched the Vostok and Mercury astronauts for bravery; they flew where no man had flown before. They also resembled another set of pioneers, the scientists at Los Alamos, New Mexico, who developed atomic power not fully appreciating how it would affect the world’s future. Orville lived long enough to see some bitter fruit of the brothers’ labor: the horrific aerial bombardments of World War II. “We dared to hope we had invented something that would bring lasting peace to the earth,” Orville told an interviewer. “But we were wrong.”

|

|