loading

loading

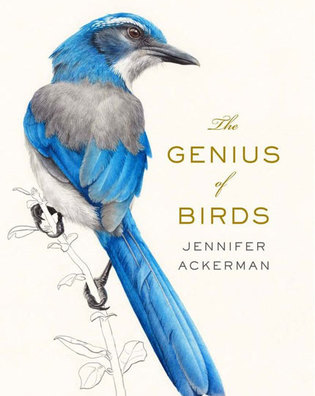

Arts & CultureReviews: September/October 2016Books on dating, birds, and Roman cuisine.  View full imageThe Genius of Birds Contributing writer Bruce Fellman is a lifelong birder and naturalist. Ackerman’s engaging and sweeping look at what researchers have discovered about the cerebral capacities of our feathered friends is nothing short of mind-altering. “In the past two decades or so, from fields and laboratories around the world have flowed examples of bird species capable of mental feats comparable to those found in primates,” she writes. There are bird artists who deliberately decorate their nests to better attract mates, food hoarders who remember the location of thousands of individual caches on average seven times out of ten—“A particularly humbling statistic when I consider my own inability to keep track of, say, my car keys or where I’ve planted my tomato seeds”—and birds such as the New Caledonia crow that have ability to fashion and use tools, a skill set once considered a definitive characteristic of humans alone. The book is filled with wide-ranging and easy-to-digest accounts of researchers and their work that may knock people off their cerebral pedestals. A consideration of Thomas Jefferson’s pet mockingbird Dick and its mastery of vocal mimicry introduces insights that support Darwin’s contention that birdsong is “the nearest analogy to language.” (Indeed, birds apparently learn to sing the same way we learn to speak.) The pigeon gets its due in a chapter on how birds have mastered direction-finding and migration—a skill that’s learned, not simply inborn. There’s even an appreciation of that much-maligned bird, the house sparrow. “Birds have never seemed dumb to me,” writes Ackerman, an accomplished birder, in this quest to understand the different sorts of genius that have made birds so successful. The result of this combination of science and unabashed delight will help readers better appreciate fall migration and the brilliant travelers on

|

|