Mark Ostow

Mark Ostow

Mark Ostow

Mark Ostow

Mark Ostow

Mark Ostow

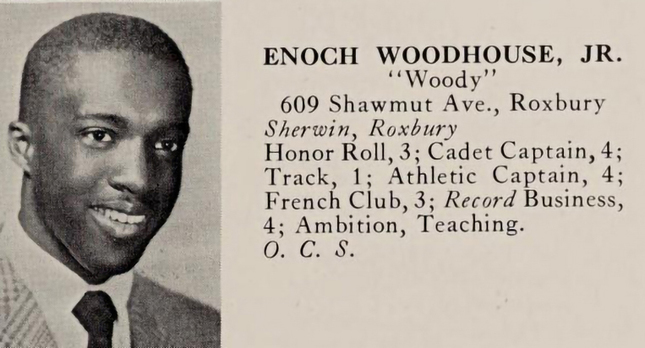

Woodhouse’s entry in Boston English High School’s 1944 yearbook.

View full image

Woodhouse’s entry in Boston English High School’s 1944 yearbook.

View full image

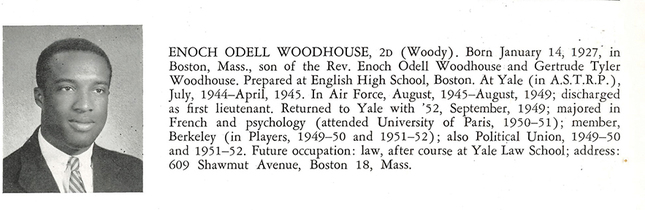

His entry in the Yale College graduates’ yearbook of 1952.

View full image

His entry in the Yale College graduates’ yearbook of 1952.

View full image

When Enoch O. (Woody) Woodhouse II arrived on the Yale campus in 1948, after serving with the now-legendary Tuskegee Airmen, he quickly felt ostracized. “When I sat down in the dining hall,” he recalls, “people would stand up and remember that they had other engagements. When I walked into a lecture hall, two or three hundred people simply ignored me.

“I got unwelcoming notes slipped under my door, and I knew they came from students in my entryway. I tore them up and laughed. Whenever I go to my reunion, I look around at my beloved classmates and realize that one of them might have written those notes.”

Now Lt. Col. (Air Force Reserve) Woodhouse, he often wears a Yale lapel pin, has served on the board of governors of the Yale Alumni Association, and—like hundreds of his fellow alums—grouses that Yale College did not admit his son. (No worries. His son excelled at Harvard.) “Yale has been progressing on the issue of race,” he says, guardedly.

At age 95, Woodhouse shuttles around the country, often adding to his impressive list of decorations and honors. In 2007, he and his fellow surviving Airmen received the Congressional Gold Medal from President George W. Bush ’68. Just before the pandemic struck, the Daughters of the American Revolution honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award. The Reverend Patrick Carroll Ward ’08MDiv accompanied Woodhouse to the DAR ceremony, and remembers that Woody, as his friends call him, asked to speak. “He thanked them for the recognition, and said based on what he had seen that day, he was more excited for the future of the DAR than he was about their past,” Ward says. “They loved it.”

“Woody has experienced more injustice in his lifetime than anyone I know.” Ward says. “But it doesn’t cause him to question his own worth. He has a terrific sense of who he is, and a certain degree of invulnerability, which I think is kind of superhuman.”

“I’m a nonconfrontational person,” Woodhouse explains. Addressing the cadets of Norwich University earlier this year, Woodhouse described how a white conductor had kicked him off the train as he was traveling from St. Louis to basic training in Texas. He was told to wait for a later train that carried only Black passengers and coal. “I feel disappointed in America,” Woodhouse told the cadets, “but that doesn’t make me your victim or anyone else’s victim. I’m proud of who I am, and you should be proud of who you are. We should all be proud to be Americans.”

Explaining how he relates to racists and racism, Woodhouse reminded the cadets of the famous passage from Canto III of Dante’s Inferno, which he quoted in Italian. Virgil expresses his disdain for those who “live in infamy,” and tells Dante, Non ragioniam di lor, ma guarda e passa: “Let’s not talk about them, but look and pass.”

“If you pass by,” he told the cadets, “you are moving to positive thinking. You’re positioning yourself in a better area.”

Woodhouse grew up in Roxbury, Boston’s African American neighborhood. He was the son of an African Methodist Episcopal minister. The family subscribed to Black newspapers, such as the Amsterdam News and the Pittsburgh Bay Courier. They printed photographs of lynchings. “My father showed me those pictures,” Woodhouse recalls. “He was telling me that there are ‘forces at work’ that don’t want us here. There are people who take joy from seeing us hanging in trees. People clapping and applauding. This is what happens when you are Black in America. Govern yourself accordingly.”

To bolster his son’s interest in education, his father took him to Harvard graduations, which he remembers fondly. “They were festive events,” he says, and he has attended them many times since. “They lasted three days, not just one and a half hours. The Harvard commencement is a ceremony. It’s quite an awesome thing.”

In high school, the aforementioned “forces at work” revealed themselves with dispatch. Woodhouse played on the varsity basketball team at Boston English High School, but wasn’t awarded a letter. (Boston English awarded him his capital “E” three years ago.) After graduating in 1944, he joined the US Army and participated in an Army Special Training Program held on the Yale campus, where he got the idea of applying to college after the war.

After attending Army Air Force officer training at Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas—where he dined in a curtained-off corner of the mess hall—Woodhouse emerged in 1946 as a 19-year-old lieutenant. “The only place I could be assigned was the 99,” he remembers. That was the all-Black 99th Pursuit Squadron, organized by West Point graduate Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. From their ranks, Davis assembled the legendary 332nd Fighter Group, known as the Tuskegee Airmen because they attended flight school in Tuskegee, Alabama.

The Airmen generally flew fighter escort missions for Army Air Force bombers in North Africa and Europe during World War II. Its pilots received 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses, and the ensemble won three Distinguished Unit Citations.

Woodhouse, however, likes to joke that “I’ve never set foot in Tuskegee and I’m not an airman” (although he did learn to fly in the Army). Trained as a budget and fiscal officer, he traveled from base to base as the unit’s paymaster, a billet that won him many friends. As he explains it: “You’re the guy that everyone has to see if they want their money.”

Arrival at Yale was an immediate culture shock. “I was living across from the Gimbel twins”—the scions of the Gimbels department store family. “Each of them had a suite, and a polo coach. There was another guy who arrived with a chauffeur who carried the boy’s clothes up to his room, and then the mother showed up with her furniture. The driver threw all the Yale furniture out of the suite and just left it in the hall.”

A high point of Woodhouse’s college experience was the year he spent studying in Paris, thanks to Columbia’s Reid Hall junior year abroad program. He also took classes at the Sorbonne and the Institut de Phonétique. (His French remains strong. He delivered remarks in French at a Lafayette Day ceremony on Boston Common in May.) As many Black Americans have found, France felt more welcoming than his home country. “The French base their superiority on culture, not on race,” he says. “When I returned to Yale, it was like traveling from the ocean back to a luxurious pond. Yale had no idea what was beyond the pond. My classmates were generally pulling ‘Gentlemen’s Cs’ because they didn’t have to work hard. They were in a holding pattern; they had good jobs waiting for them.”

Woodhouse was one of four African Americans among the 984 graduates of the Class of 1952. One of them is Nathan Garrett, who reports smoother sailing for himself, and for two of his Black friends who roomed together in Pierson College, than Woodhouse experienced during his time at Berkeley College. “There was both good and bad at Yale,” Garrett remembers. “I enjoyed myself there, mostly.” He edited the Pierson newspaper, The Slave (!), and operated the snack bar in the basement of the college. As a student at Pierson, Garrett of course noted that the college had “a small enclave of buildings referred to as the ‘Slave Quarters.’” But as he writes in his memoir—titled A Palette, Not a Portrait—“I have had many great opportunities in life since Yale, and I credit Yale for a lot of them.”

In a class remembrance, one of Garrett’s roommates—the late physician Charles Payne—noted that “Pierson, with a reputation as being very ‘white shoe’ and with ‘Slave Quarters,’ seemed to be taking a risk in reducing its real estate values but we actually enjoyed the ambience.” Payne’s daughter Deborah also went to Yale. His obituary states that they were “the first African-American, father-daughter team to graduate from Yale.”

After college, Woodhouse attended school at both Boston University and Yale Law School, emerging with his JD degree from BU in 1955. He taught physics and chemistry at Roxbury Memorial High School, worked as a State Department courier, and was appointed an assistant corporation counsel for the city of Boston by mayor John F. Collins.

In 1970, inspired by Harvard’s integrated Board of Overseers—its first Black member, diplomat Ralph Bunche, joined in 1959—Woodhouse resolved to run for a spot on the Yale Corporation. “I thought Yale was ready for a Black Corporation member,” he says, “but not everyone did. People told me, ‘We’re not ready for that.’” Woodhouse ran as a petition candidate—a candidate not officially sanctioned by the university. (Yale recently eliminated the petition process.) He concentrated on collecting signatures from expatriates. “I knew the thinking of American Yalies,” he says. “Overseas was a different breed.”

To this day, Woodhouse remains upset about the results. When Yale sent its official ballot to alumni, it included two other Black candidates: federal judge Leon Higginbotham Jr. ’52LLB and Stanley B. Thomas Jr. ’64, an executive at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. In addition, two of the nominees were members of the class of 1952, a move Woodhouse interprets as intended to thwart his bid. Higginbotham became the first Black Corporation member, an outcome Woodhouse found especially galling because he had sought Higginbotham’s support for his own candidacy many months before the ballot was promulgated.

“The deck was stacked against me,” Woodhouse says. As in all Corporation elections, no details of the vote were released. (“The official results of Yale Corporation elections are never disclosed,” the New York Times reported in an article announcing the newly elected Yale trustee.) “Who could I protest to?” he asks. “It would have been pointless.” Asked for records of the election, a Yale spokeswoman said that the Corporation isn’t directly involved in producing the Alumni Fellow ballot, and therefore its records would not have any relevant information about the candidacy. A spokesman for the Yale Alumni Association—which today oversees the nomination process—declined to comment because the YAA was not involved in the process in 1970.

Two years later, Woodhouse was appointed to the board of governors of the AYA. He, Connie Royster ’72, and Ronald Lindsey ’72 were the first Black members of the AYA board. Woodhouse still speaks with awe about the meetings with luminaries such as John Hay (Jock) Whitney ’26 and William Beinecke ’36. He remembers Beinecke as “just the nicest guy. We once had a meeting at one of Whitney’s houses, and he encouraged us to use the bathroom—there was a small Matisse right above the commode. To meet these wonderful people took away the sting from some of my bad experiences.”

That same year, Woodhouse threw himself into another contentious election, in Boston’s redistricted Ninth Congressional District. Opposing him was his Boston University Law School classmate, the incumbent Louise Day Hicks, often vilified for her opposition to court-ordered busing in the city. Woodhouse also opposed mandatory busing, and considered Hicks to be a friend. “She got a bum rap,” he says. “She was honestly representing the views of her constituency.” Hicks beat Woodhouse and several other candidates in the Democratic primary, then lost to independent candidate Joseph Moakley in the general election. Woodhouse has a simple explanation for the outcome: “Black people didn’t vote for me, and white people didn’t vote for me either.”

After many years of private legal practice, Woodhouse embarked on his retirement/victory tour, which generally finds him crisscrossing the country to speak at events honoring African American veterans. A recent high point: attending the 2017 dedication of West Point’s Davis Barracks—named to honor the founder of the Tuskegee Airmen. Davis was famously “silenced” during his years at West Point: his fellow cadets refused to speak to him. “He got the silent treatment, I got the indifferent treatment,” is how Woodhouse compares their college experiences.

In his speech to the Norwich University cadets, Woodhouse described standing next to the West Point commandant as the entire cadet corps passed before them in review. Woodhouse’s reaction: “That was just awesome, man.”

Norwich professor Travis Morris had taken thirty students to Boston’s Union Oyster House in the spring to hear Woodhouse speak. “He seems to be energized by the next generation,” Morris says. “It’s so much easier not to put yourself out there, but he’s the opposite. When the sunlight is setting, he’s letting that light shine into another generation who will hopefully carry that baton.”

Woodhouse now lives just a few miles from where he grew up. He can often be seen on Sundays walking to Trinity Church, the H. H. Richardson–designed Episcopal pile that dominates Boston’s Copley Square. He is proud of his longstanding membership in Boston’s Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, a ceremonial militia that purports to be “the oldest chartered military organization in the western hemisphere.”

I asked about his growing fame, the requests to serve as a guest speaker and visiting fellow at military academies across the country. How does he feel about becoming a star after being ignored and insulted for decades? Woodhouse contemplates his latest turn of fortune and chuckles: “People aren’t interested in me because I’m so famous. It’s because I’m the last SOB left standing.”

loading

loading

2 comments

-

Jeff Danziger, 8:36am July 13 2022 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Gary Jusela, 3:41pm August 26 2022 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Very nice piece. Enjoyed it.

This article is both depressing, due to Yale's deep racist history, and inspiring due to the unbelievable determination, strength and intelligence of Enoch Woodhouse to rise above all of who and what he faced both in college and for many years beyond that. He truly is a survivor.