Manuscripts and Archives

Weir Hall in the 1920s. George Douglas Miller, Class of 1870, built the building and its raised courtyard in imitation of Magdalen College at Oxford. The octagonal tower at right was originally part of Alumni Hall on the Old Campus.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

Weir Hall in the 1920s. George Douglas Miller, Class of 1870, built the building and its raised courtyard in imitation of Magdalen College at Oxford. The octagonal tower at right was originally part of Alumni Hall on the Old Campus.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

Manuscripts and Archives

The picturesque, tree-shaded sculpture garden of the Yale University Art Gallery, secluded in the middle of a busy campus block, is a favorite spot for a quiet break. But its odd position on campus—raised above the street, tucked among disparate buildings with little apparent relation to any of them—has made more than one person wonder how it came to be. The story involves one George Douglas Miller, Class of 1870, who singlehandedly pursued a very specific dream: to build a replica of the University of Oxford’s Magdalen College courtyard in the backyard of the Skull and Bones society.

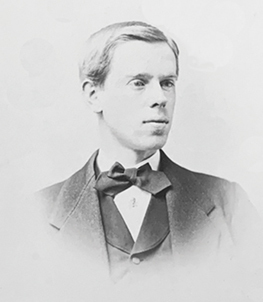

Miller grew up in Rochester, New York, where his father was a judge. After graduating from Yale, Miller spent a decade in New York before moving with his wife to New Haven, where he began investing in real estate. In the early 1880s, the Millers likely lived in a house on York Street, on what is now the site of the sculpture garden. In 1883, their two-year-old son Samuel died of diphtheria. Miller later described the loss as “the one real sorrow of my life”; he soon left New Haven and went on a series of world travels. He and his family eventually settled in Albany, where he continued his career in real estate.

But Yale and New Haven remained on Miller’s mind. He was a devoted Yale man, but he was an even more devoted alumnus of Skull and Bones. He donated his island retreat in the St. Lawrence River—known as Deer Island—to the society, and he collected artifacts and memorabilia for its tomb on High Street. By 1905, he had started buying up land on Chapel and York Streets in the same block as Bones and his former home. These purchases included Chapel Street storefronts, houses, and a large open area in the middle of the block.

Letters in the Yale archives from Miller to Yale secretary Anson Phelps Stokes, Class of 1896 (another Bonesman), reveal his thinking. In 1909, he wrote about his plan for a cloister or “yard.” It would be a place of “quiet, restful beauty” that “in the years to come will be hidden away more and more by Chapel Street shops.”

But while Miller knew what he wanted to build, he never seemed exactly sure of its purpose. He imagined that it could be part of Skull and Bones, though he conceded that it might be many years before the society would have a need for it. His most frequently expressed idea was that the buildings surrounding his courtyard could be residences for graduate students or young New Haven professionals.

Construction was under way by 1911. Miller brought in soil to raise the ground level of the courtyard, and he hired the architecture firm of Tracy and Swartwout to design the buildings. (Evarts Tracy, Class of 1890, was a fellow Bonesman.)

The first phase of construction was a slender stone building that indeed copied elements of Magdalen College. He also tried to replicate medieval construction methods, as he later wrote: “I took my New York architect to Oxford to breathe (thru him) into this building the real spirit of the Middle Ages. I even stopped the cutting of the window mullions by machinery and imported stone masons who did their work not by contract.”

In 1911, when Yale tore down Alumni Hall to build Lanman-Wright Hall on Old Campus, Miller asked the university if he could have the octagonal stone towers and entrance arch from the building. He had them rebuilt at the rear of the Bones tomb as an entryway to his courtyard; it remains as a passage from High Street to the sculpture garden.

At some point, however, Miller ran out of money for the project. He conceded to Stokes that “of course, it was an error in judgment, my spending so much money in that rear yard.” In 1917, he arranged to sell all his holdings on the block—including the courtyard, the building, and the Chapel Street property—to the university. A plaque was placed on the building, at Miller’s request, “to commemorate his only son, Samuel Miller (1881–1883), who was born and died on these premises.”

Miller knew that his project was considered a folly. As he wrote to Stokes at the time of the sale, “Am I not myself painfully aware that I will go down in the Annals of Yale as a crazy crank? But crank I am, thank God—a crankus crankorum, who is very proud of what he tried to do for [Skull and Bones], for Yale, and for Yale and Bones men yet unborn.”

Miller’s building sat unfinished until 1924, when the architecture department of the School of Fine Arts took it over. It was christened Weir Hall in honor of the school’s founding dean, John Ferguson Weir. In 1963, when the department moved to what is now called Paul Rudolph Hall, Weir Hall was annexed by the adjacent Jonathan Edwards College; it now houses the college’s library, student rooms, and faculty offices. Miller’s raised courtyard has long been used by the Art Gallery to display sculpture; in 1975, an auditorium was built beneath it.

Miller’s dream was cut short, but Yale soon took up his idea of building Oxbridge-style courtyards: first in the Harkness Memorial Quadrangle—built between 1917 and 1921—and then in a succession of buildings in the 1920s and 1930s. Whether such architecture aided in “the moral and intellectual atmosphere of the College and the development of the finest type of manhood,” as Miller hoped his yard would, is a question for another day.

loading

loading