Horowitz papers, Irving S. Gilmore Music Library

Pianist Vladimir Horowitz was photographed in Cleveland during May 1974, shortly before his first public concert in five years. The concert took place not long after a few Yale undergrads had convinced him to start performing again.

View full image

Horowitz papers, Irving S. Gilmore Music Library

Pianist Vladimir Horowitz was photographed in Cleveland during May 1974, shortly before his first public concert in five years. The concert took place not long after a few Yale undergrads had convinced him to start performing again.

View full image

Courtesy Daniel DiMaio ’74

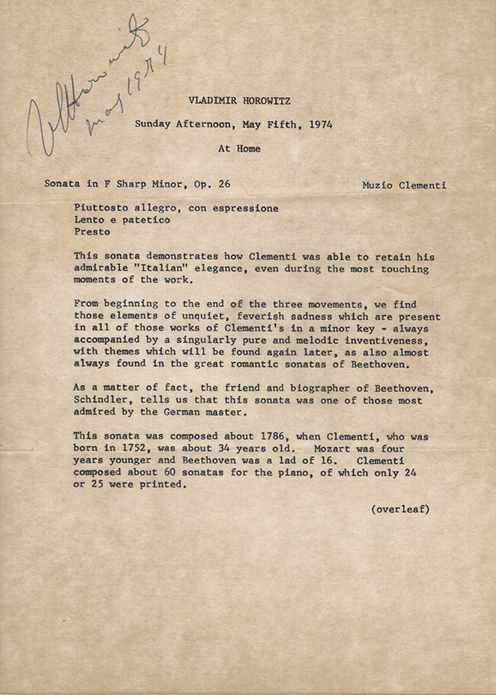

The program for Horowitz’s private concert, signed by the pianist.

View full image

Courtesy Daniel DiMaio ’74

The program for Horowitz’s private concert, signed by the pianist.

View full image

Courtesy Daniel DiMaio ’74

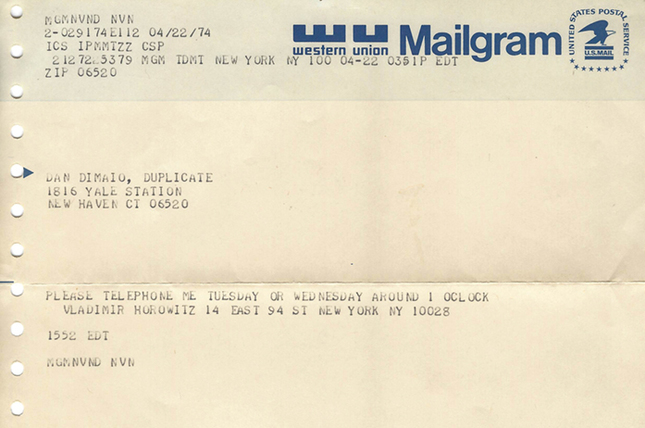

The telegram he sent to the author while arranging the event.

View full image

Courtesy Daniel DiMaio ’74

The telegram he sent to the author while arranging the event.

View full image

On April 22, 1974, I received a telegram from Vladimir Horowitz, instructing me to telephone him in the next day or two. Why did the world’s greatest living pianist want to talk to me, a Yale College senior with no musical credentials or aspirations? In fact, this telegram was only the latest in a series of communications Mr. Horowitz and I had over several months. I was executing my plan to lure him back onto the concert stage.

Mr. Horowitz was music royalty. He was married to Wanda Toscanini—daughter of Arturo Toscanini, the legendary conductor—and he played at the White House for three presidents. He won 25 Grammy Awards. His concerts were dazzling virtuoso performances that whipped audiences into a frenzy not seen since Franz Liszt had performed a century earlier.

Despite such acclaim, on several occasions Mr. Horowitz stopped performing in public, sometimes even at the height of his career. He did not disclose the reasons for these absences, and the longest one lasted 12 years. In the spring of 1974, he had not performed in public for five years, and because he was 70 years old, the classical music world despaired of ever hearing him perform live again.

My story begins in the fall of 1970, when Mr. Horowitz became an associate fellow of Silliman College, my residential college. (He accepted this appointment with the proviso that—in his words—“I do understand that there are no duties and responsibilities attached to such Associate Fellowship.”) Two years later, Silliman hosted a small private reception for Mr. Horowitz, organized by John Palmer, dean of the college, and two students, Michael Palm ’73 and Thaddeus Carhart ’72.

The next year, I decided to follow up on this first meeting, with the unstated goal of nudging Mr. Horowitz toward performing in public again. I sent him a letter suggesting that a small group of students could visit him at his home. In a return letter, he expressed interest in a possible visit and said he was willing to correspond further. In April 1974, a letter from his secretary divulged his telephone number—a valuable and closely held secret. During the following few weeks, I talked to Mr. Horowitz three or four times on the phone. We discussed a variety of topics, while I engaged in the delicate task of encouraging him to play for us without scaring him off by seeming too insistent or eager. Once I gained his trust and convinced him that I could assemble an enthusiastic young audience, belying his concern that we “would rather go to a football game,” we planned a recital.

During our conversations, Mr. Horowitz wanted to learn about us: how many men and how many women would attend his recital, how old were we, and what would we like to hear him play. He told me that he wanted only students to attend, not faculty, and he insisted that there would be no public announcement, lest we be besieged with demands for invitations from other students, faculty, or even the general public.

So, relying on landline phone calls, quiet conversations in the Silliman College courtyard and dining hall, and pieces of paper taped to dorm room doors, I extracted promises of secrecy and assembled a group of students eager to hear Mr. Horowitz play, perhaps for the last time. There was a last-minute change in venue, from the Horowitzes’ Connecticut home to their Manhattan residence. He sent the telegram for reassurance, once again, that I could deliver an appreciative audience. On Sunday, May 5, I managed to corral more than thirty exam-harried Yale students onto a chartered bus to New York.

When we arrived at the Horowitz townhouse on the Upper East Side, we were ushered through a mirrored vestibule into the dimly lit, incense-filled hallway. I led the way cautiously up the curving flight of stairs to the second floor, where we were greeted by Madame Wanda Toscanini Horowitz and her sister, Wally. They escorted us into what they called “our Silliman room,” dominated by a concert grand piano that had been hoisted in through a window. Some personal friends invited by the Horowitzes gathered in the room across the hall. During one of our conversations, Mr. Horowitz had explained, “They already know how I play,” so they yielded the choice seats by the piano to us.

A forty-five-minute wait made me fear that Mr. Horowitz had had second thoughts about performing. But eventually, he descended from the upper floors, formally dressed in a suit and his trademark bowtie. As a measure of the esteem in which the great pianist was held, his friends stood and applauded when he finally appeared. He entered our room and, using our college nickname, said, “So, these are our Sillimanders.” Before sitting down at the piano, he asked, “And, is Mr. DiMaio here?” I mustered enough self-composure to inform him that I was, indeed, present. Shaking my hand, he thanked me for bringing him his audience.

Mr. Horowitz appeared somewhat nervous at first, but he was witty and charming, telling anecdotes, joking with Wanda, and exhibiting an interest in us. He wanted to know, for example, if any of us hoped to be professional musicians. He was anxious for us to enjoy the afternoon. He warned us that the room was small and the piano was large, and therefore our eardrums might suffer. He apologized for any wrong notes he might strike, explaining that this was not a concert, and he assured us that no piece was very long, so he hoped that we would not be bored.

Mr. Horowitz had chosen pieces to illustrate musical points, and he handed out a typed program in which he briefly described each piece. He first crisply played a Clementi sonata, because he felt Clementi was a fountainhead from whom later composers borrowed many ideas. He next presented a wonderfully varied interpretation of the Schumann Kinderszenen, demonstrating the supreme elegance of those miniatures. After a short break, Mr. Horowitz devoured the Chopin Polonaise-Fantaisie. Before playing, he explained that it was one of Chopin’s most difficult compositions, both to play and to listen to. In a slow opening arpeggio, Mr. Horowitz missed some notes. While continuing to play with his right hand, he waved his left hand dismissively as if to brush aside a minor lapse almost beneath his notice. He rallied, and the performance was stupendous.

After a “simple” Chopin mazurka, he ended with Scriabin’s Vers la Flamme (Toward the Flame). In this 1914 composition, Mr. Horowitz saw Scriabin presenting an awesome preview of the ultimate destruction of the world by the atomic bomb. The piece was performed accordingly—causing one member of our group to gasp, later on, that she had stopped hearing individual notes and instead felt engulfed, even threatened, by the music.

After each piece, Mr. Horowitz would turn to us and ask, “Did you like it?” He seemed genuinely pleased when we vigorously affirmed that we had. As the program progressed and we continued to voice our approval, he visibly relaxed and appeared to enjoy himself greatly (although, when he played, his jaw remained tightly clenched). He was generally quiet, his body almost immobile on the piano bench, leaving the pianists in our group to marvel at the position of his hands and his flat-fingered technique. When his interpretation demanded it, he became more animated: half rising from the bench to add force to the base octaves in the Polonaise, or lowering his forehead practically to the keyboard while eliciting the perfect response from the piano in the Schumann.

When he finished playing, we presented Mr. Horowitz with a pewter tankard emblazoned with the Silliman College seal. He seemed delighted with this gift as he waved it over his head and proclaimed, “Now I can go to college!”

The most engaging aspect of Mr. and Mrs. Horowitz was their unassuming demeanor. During one of our telephone conversations, Mr. Horowitz mentioned that there would be people present with recording equipment and cameras. I expected a professional recording setup and photographer appropriate to the occasion. Instead, from under her chair, Mrs. Horowitz produced a small cassette recorder and a Kodak Instamatic camera topped by a flash cube.

For us, the affair was unique and unforgettable. We heard a great artist work his magic in the most intimate of settings. The sight of Mrs. Horowitz pouring refreshments for her guests at a reception after the performance emphasized that the event was important for them, too.

After we returned to Yale, we learned that a concert had been scheduled for May 12 in Cleveland, exactly one week after he played for us. In an interview published in the New York Times a few days before the concert, Mr. Horowitz stated, “Just last Sunday, I invited [some Yale students] here to my house. . . . I played . . . and it went very well. I thought, if I can play so well here, why not on a stage?” The Washington Post reported that after Mr. Horowitz had played for us he told one of his guests, “I think this is marvelous. I feel wonderful. I could play a concert right now.” That guest was the impresario Harold Shaw, who leapt at the suggestion and immediately asked him if he would like to perform in public one week later. “The decision was made on the spot,” and the Cleveland concert was hastily arranged.

When Mr. Horowitz discovered that he could overwhelm a small, hand-picked audience in his living room, he could not resist repeating this conquest on a larger scale. In Cleveland, he performed much the same program we had heard, and the results were predictable; the headline in the New York Times used the word “flabbergastingly.” Mr. Horowitz continued to perform in public until his death in 1989, at age 86.

Near the end of his life, Mr. and Mrs. Horowitz decided to donate their personal music collection and papers to Yale. The collection, housed in the Gilmore Music Library, consists of 164 boxes containing letters, documents, photographs, annotated musical scores, memorabilia, hundreds of unreleased recordings of his live recitals, and a pewter tankard from Silliman College.

loading

loading