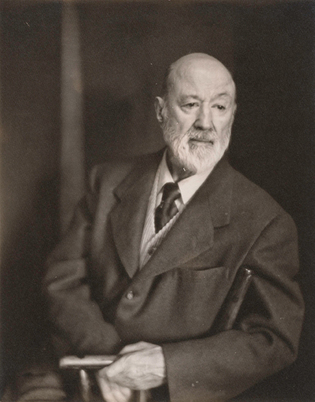

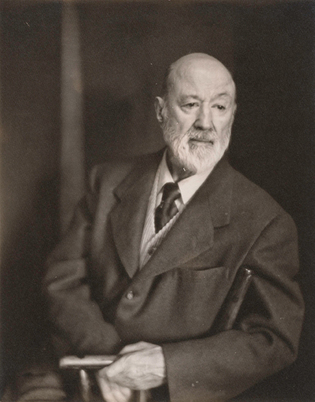

Clara Sipprell/National Portrait Gallery

Charles Ives ’98—that’s 1898—was brilliant in many fields, and far ahead of his time in musicianship.

View full image

There are times when the music of Charles Ives, Class of 1898, turns my mind inside out.

Consider his short “Fourth of July piece.” The vast majority of Americans have heard at least a few Fourth of July songs: “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “My Country ’tis of Thee” leap to mind, cheerful and patriotic, whether sung sweetly by children in a music room, sloppily by teenagers waving flags and beer bottles, or joyfully by elders. Yet Ives opens his “Fourth of July” composition (1912) as if Mr. Hyde were skulking toward his next victim. (For those who haven’t read Robert Louis Stevenson, go ahead. If you can handle it.) Everything is low, quiet, and eerie for a minute and a half, until the flutes pipe up for a few seconds and the violins follow. A trumpet is blown. Only then do we hear cheerful notes for the Fourth of July.

Next, the orchestra decides to turn itself into a band. The trumpet blares happily, the string instruments strike up a march, the piccolo runs all the way up to the extremity of its notes—and then, suddenly, Ives crashes every note to the ground. It’s a wild cacophony. But the musicians start up again, and semi-reasonable order is restored.

Then, abruptly, we hear nothing. What? Is it over? No. Ives was merely pausing before he called up the ending—which comes right at us in one enormous, ferocious, crazy blast.

And mind you, that was just one single section in a four-part piece.

Charles Ives (1874–1954) was born in Danbury, Connecticut. He was a genuine genius. In fact, he was a genius in more than one area. He was an actuary, working with statistics and mathematics to ensure that his clients used their money safely. He was also a sharp businessman, and he set up his own insurance agency with a friend. But music—new and different music—was his great passion.

He came to it because of his father. George Ives played the cornet, directed bands and choirs, and led theater orchestras. Young Charles was quickly hooked. According to the Charles Ives Society, Ives’s father

came home one day to find the five-year-old banging out the Ives Band’s drum parts on the piano, using his fists. George Ives’s response gave the first impetus to his son’s career as a musical innovator. Rather than saying, as most parents might, “That’s not how to play the piano,” George observed instead, “It’s all right to do that, Charles, if you know what you’re doing”—and sent the boy down the street for drum lessons. Charlie never did stop using his fists on the piano, and was eventually notorious for requiring a board to play the Concord Sonata.

When Charles was only 12 years old, he started playing church music on the organ. He learned not only harmony and counterpoint, but also composing. The town band played his very first composition (although it’s possible that one reason for such a kindness was that his family was quite well off).

I bring all this up because 2024 would have been Ives’s 150th year. Since he can’t be with us, it’s up to us to celebrate him, his life, and his music. In Ives’s day, his music was mostly ignored. Now, the list of those celebrating him is nearly endless: Indiana University, New England Conservatory, San Francisco Classical Voice, Western Connecticut Youth Orchestra, Charles Ives Music Festival, and certainly many more, including—of course!—Yale’s own Norfolk Summer Chamber Music Festival.

But perhaps most poignantly: in 1972, James Sinclair, a young musician, had found work as an assistant professor of music at Yale, and had started leafing through reams of paper in the archives—papers covered with musical notes. They are the Charles Ives Papers, and they reside in the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library of Yale University.

Sinclair seized the opportunity to resurrect more of Ives’s extraordinary music. He formed a troupe of musicians, and in 1974, Orchestra New England (ONE) was born. ONE has been performing in New England ever since, welcoming excellent instrumentalists who come in and out, as needed or as they like.

As Sinclair told an interviewer: “There is such a deep humanity in Charles Ives that that’s a charismatic thing. This is a friend you would never abandon.”

I only wish that Ives could have been there to receive that beautiful compliment.

loading

loading