loading

loading

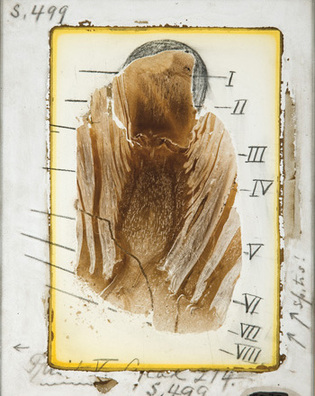

Arts & CultureObject lessonFlowers in stone Leo J. Hickey, professor of geology and curator of paleobotany at the Peabody Museum, specializes in the evolutionary history of flowering plants.  Mark MorosseA top-to-bottom cross-section of a fossilized Cycadeoidea dakotensis flower, about six inches long, attached to a piece of plate glass and then ground down by hand until wafer-thin. The numbered lines mark the levels for cross-cut sections to be made on the adjacent slab. View full imageFlowers are among the most ephemeral objects in nature, meant to attract pollinators, then to be quickly lost or transformed as the plant sets fruit. Yet the longitudinal slice in this picture is from a flower that has endured for over 125 million years. It has lasted partly because it was made of tough stuff -- a stout stem inside thick bracts and heavy fibers -- and partly because its tissues were eventually embedded in silica, a mineral harder than steel. This flower belongs to a bizarre group called cycadeoids, extinct precursors of today's flowering plants. Cycadeoids had barrel-shaped trunks two to three feet high, with a crown of palm-like leaves and flowers. Farmers have frequently mistaken the fossilized trunks for petrified versions of old-fashioned straw beehives. A cycadeoid trunk was found standing in an Etruscan tomb more than 4,000 years old, making it the first known fossil collected. Yale's Peabody Museum has the world's largest collection of cycadeoids, with somewhat over a thousand trunks and pieces. The story of how they came here began in the gold rush towns of the Black Hills of South Dakota. In 1896, O. C. Marsh ’60, the Peabody's first director, heard that cycadeoids had been discovered there and instructed his agent, H. F. Wells, to begin acquiring them. One of the best sites lay on the south rim of the Hills, and a rush had developed several years earlier to collect and sell the trunks that littered the outcrop. By the time the U.S. government got around to protecting this area as the Fossil Cycad National Monument in 1922, not a single cycadeoid remained on the surface. The only Black Hills cycadeoids now available for study are those saved by Wells and other scientific collectors. The final episode in this story involves George Wieland ’00PhD, who arrived at Yale in 1898 to study vertebrate fossils but soon developed a passion for cycadeoids that would last through a 50-year career. The size and hardness of cycadeoid trunks had always discouraged their study, but Wieland found that he could use the technology of local gravestone cutters to slice the trunks into half-inch slabs. He pasted pieces of these onto plate-glass rectangles and then laboriously ground them down, by hand, until they were thin enough to reveal the incredibly detailed anatomy within. Today, even though they have been extinct for over 85 million years, the cycadeoids are one of the best-known groups of plants -- thanks largely to George Wieland's obsession.

The comment period has expired.

|

|