loading

loading

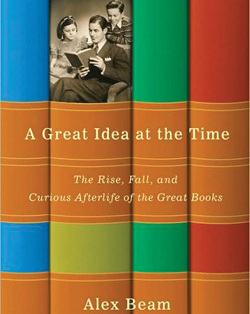

Arts & CultureFamily entertainmentBook review Carlo Rotella ’94PhD, director of American studies at Boston College, writes for the New York Times Magazine and the Washington Post Magazine.  View full imageThe story of the Great Books movement may not seem obviously ripe for Hollywood, but it begins to have possibilities if you look at it the right way. The main characters are vivid and promising. There's the University of Chicago's boy-wonder president Robert Maynard Hutchins ’21, ’25LLB, who deployed not just a fine intellect but also dreamboat looks and a sonorous upmarket pitchman's style to champion the life of the mind. (Picture George Clooney in the role, or Thomas Haden Church, of Sideways fame, cleaned up a bit.) There's Mortimer Adler, the self-promoting philosopher who clawed his way through stiff competition to win lasting distinction as one of the most annoying smart people of all time. (Get me Danny DeVito!) And there's the marketing visionary William Benton ’21, who owned the Muzak Corporation and Encyclopaedia Britannica, pioneered the Orwellian use of audience cue cards ("APPLAUSE"), and moved a million units of the 54-volume Great Books of the Western World by selling the promise that passing familiarity with Epictetus would help consumers get laid and impress the boss. (Stay with me on this one: Christopher Walken as Benton. Imagine his monologic riff on Great Book Number Seven, which contains Hippocrates' On Hemorrhoids.) These characters play out a story that draws lasting power from its unresolved inner tensions. At once elevated in its ambitions and tinged with seediness, animated by democratic and elitist principles, rife with generosity of spirit and grasping self-love, the Great Books movement awaits its apotheosis in the kind of low-rolling epic that Hollywood does best. (By the way, there's a tasty walk-on for Angelina Jolie as Julie Adams, star of Creature from the Black Lagoon, an outspoken celebrity reader of the Great Books.) Until the movie is made, we have Alex Beam's self-described "brief, engaging, and undidactic history." Beam, a columnist for the Boston Globe and the author of Gracefully Insane: Life and Death Inside America's Premier Mental Hospital and two novels, set out to write a book "as different from the ponderous and forbidding Great Books as it could possibly be." (Beam wrote an article about Yale University Press in the previous issue of this magazine.) He has succeeded in that ambition, perhaps too well. He has concisely traced the history of the idea of educating oneself by reading classics of lasting significance and relevance, afforded his characters ample opportunity to tread the boards and speak their lines, and captured the movement's middlebrow charm as well as its self-serious blowhardism, but he may be too modest and plainspoken a chronicler to tell the story on the mock-magisterial scale it begs for. The tale begins in the Victorian era, when there flourished an enthusiasm for the notion that reading lasting works of supreme quality chases out the inferior ideas and influences to be had from ordinary reading. That enthusiasm raised the stakes of the struggle on university campuses between proponents of the established classically oriented curriculum and insurgents supporting the elective-heavy college catalog. Beam's first protagonist, John Erskine, the professor at Columbia University who worked out the fundamentals of the Great Books curriculum as it would be promulgated in America, ranged afield to engage an expanded student body in settlement houses, YMCAs, and American Expeditionary Force bases in France during and after World War I. Erskine handed off the baton to Hutchins and Adler and their disciples, who threw themselves into the work of building an institutional basis for a curriculum centered on reading and discussion of an approved list of books of time-tested importance, an approach that marginalized secondary works of criticism and the specialized scholars who wrote them. The institution-builders proceeded on multiple tracks, establishing the Great Books at Chicago, Columbia, Yale, and other universities and also looking for ways to bring the good news to the people. Enter Benton, who teamed up with Hutchins and Adler to flog The Great Books of the Western World to postwar American consumers. When you consider what they were selling -- 54 volumes costing hundreds of dollars, printed in a hard-to-read double-columned, nine-point Fairfield type, and heavy on philosophical and scientific tracts rather than literary prose (Apollonius of Perga, author of the deathless On Conic Sections, made the cut, but Moliere, Dickens, Flaubert, and Twain did not) -- you can't help but admire their success in creating a pop culture phenomenon. Beam accounts for it with a thumbnail account of cultural conditions that nourished such middlebrow ventures in the 1950s: an expanding middle class with increased purchasing power and a hunger for cultural capital, the rise of general education, the flourishing of mutually reinforcing institutions (like the Book-of-the-Month Club) dedicated to the principle of culture that elevates as it entertains, and a postwar craving for community that encouraged ordinary citizen-consumers to band together into Great Books discussion groups. Sheer sales chops also played a part. Benton understood the subtleties of his product's mass-market snob appeal, and he knew how to speak to his ideal consumer's "basic desires" and anxieties. "How does he become more attractive to the opposite sex? How does he impress people at a party? How does he learn what he needs to know in order to get promoted?" The marketers' deliberations on selling intellectual potency in postwar America are fascinating, but I wish Beam had told us more about the foot-in-the-door experiences of the salesmen who took the Great Books to the people, just as I wish he had told us more about what actually went on in the discussion groups. He offers tantalizing glimpses of both. The moment didn't last. Beam identifies the so-called "culture wars" as a key factor in the decline of the Great Books as a business enterprise and an intellectual movement after the 1960s. Both the multiculturalist critique of the notion of a Western canon and the hijacking of that notion by conservative ideologues helped sweep the Great Books to the margins of American education and culture. And yet they live on. The Great Books still maintain footholds on campus in the core curriculum (as at Columbia or Chicago) or in special programs (like Directed Studies at Yale), and they form the entire curriculum at St. John's College, where Beam finds the students endearingly passionate and naive about the life of the mind. Beyond the academy, Beam finds echoes of the golden age of the Great Books in the movement's vestiges and by-blows: in the few remaining discussion groups, in the lives of adults who grew up in households where the 54-volume set held sway, and in later book-centered efforts to merge self-improvement and marketing -- like Oprah's Book Club -- that he treats as extensions of the original impulse. The Great Books movement does not lack for assailable blind spots, buffoonery, and hucksterism. Adler's Syntopicon, for instance, an index of ideas hawked as an add-on to the Great Books, is the sort of populuxe gadget for boosting brain power that should rightly have been sold in the back pages of comic books. But it's a mistake, as Beam astutely perceives, to dismiss Adler and company as mere popularizers or profiteers, or to doubt their original seriousness of purpose in attempting to transform the nation's intellectual life. They knew that any attempt to engage ideas for their own sake runs the risk of being perceived as silly by Americans, who like their ideas connected to material life: tangible stuff to buy and sell; power, money, and sex. Accordingly, when the purveyors of the Great Books set out to take America by storm, they did not fear to advance on the multiple fronts they knew they had to conquer -- not just into the academy, but also into the rough-and-tumble of consumer culture. Their rise and fall makes for a good story because, while their posturing and excesses are inevitably good for laughs, their successes and their motivations are not easily dismissed.

The comment period has expired.

|

|