loading

loading

Old YaleAbraham Lincoln spoke hereJudith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.

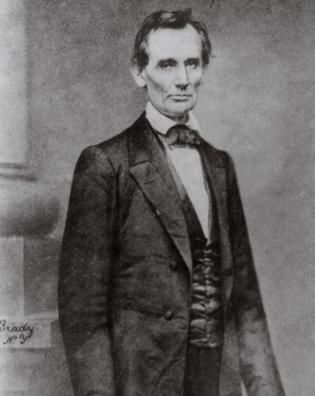

Matthew Brady/ Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionAbraham Lincoln posed for this portrait on February 27, 1860, a week before he gave the speech in New Haven that introduced his image as a rail splitter: "I am not ashamed to confess," he said, "that 25 years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat boat—just what might happen to any poor man's son." View full imageIn 2009, the nation will mark the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth. As the Bicentennial Commission established by Congress stated, "During the gravest crisis in American history, Lincoln preserved the Union, led the effort to eradicate slavery, and articulated the best aspirations of American democracy." Lincoln's ability to persuade the American people that slavery is wrong was forcefully demonstrated on March 6, 1860, in an impassioned speech before a large New Haven audience that included Yale students and alumni. The two-hour oration at Union Hall, wrote historian Waldo Braden in Abraham Lincoln, Public Speaker (1988), "launched his Rail Splitter image," which would figure heavily in his campaign for the Republican nomination and the presidency that year. Lincoln also, for the first time, condemned the Democrats for stoking fears about the "struggle between the white man and negro." These themes and their delivery played well with the crowd, according to the local paper, the Palladium. "There was witnessed the wildest scene of enthusiasm and excitement that has been seen in New Haven for years." In 1860, Yale student opinion on slavery and secession was divided, mainly according to home-state loyalties. Town and gown were bustling: New Haven was the largest city in the state, with a population of 40,000, and Yale one of the largest colleges in the country, with a student body of nearly 650. Lincoln was actively seeking the Republican Party's nomination for president, and two New Haven men arranged his visit to New Haven: James F. Babcock, editor of the Palladium, and John D. Candee, Class of 1847, Yale Law 1849. Candee wrote to Lincoln on February 28: "On Monday we expect to hear you in New Haven. You will please stop at the New Haven House [a hotel]. It is unnecessary to give names of friends here as so many of us have met you & we shall find you at the Cars or Hotel." For Leonard Bacon, Class of 1820, pastor of Center Church, Lincoln's speech would have special meaning. Bacon was an active antislavery worker and writer, and his Slavery Discussed in Occasional Essays (1846) was said to have influenced Lincoln. Bacon wrote: "If that form of government, that system of social order is not wrong—if those laws of the Southern States, by virtue of which slavery exists there, and is what it is, are not wrong—nothing is wrong." Lincoln, in his New Haven speech, said: "If Slavery is right, all words, acts, laws, and Constitutions against it, are themselves wrong, and should be silenced, and swept away. If it is right, we cannot justly object to its nationality—its universality; if it is wrong they cannot justly insist upon its extension—its enlargement." Lincoln closed with: "Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government, nor of dungeons to ourselves. Let us have faith that right makes might; and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty, as we understand it." That May Lincoln was nominated as the Republican candidate for president, and while he never returned to Yale, he continued to have direct and indirect contact. On July 3, 1860, from his home in Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln wrote to Yale president Theodore Dwight Woolsey on behalf of a fellow Springfield lawyer, Volney Hickox, Class of 1857. In the original letter, preserved in Woolsey's papers at Yale, Lincoln wrote that Hickox was "fully worthy of the additional academical honors he seeks at your hands." The honor Hickox sought and received was a Master of Arts degree, customarily awarded after an alumnus successfully completed a course of professional apprenticeship or graduate study. Lincoln's letter for Hickox was additionally endorsed by one A. Hale, whom I found to be Rev. Albert Hale, Class of 1827, Yale Divinity School 1831. In 1839, Hale had become a pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church in Springfield, which Lincoln attended. Hale once said of his famous congregant's life in Springfield: "Abraham Lincoln has been here all the time, consulting and consulted by all classes, all parties, and on all subjects of political interest, with men of every degree of corruption, and yet I have never heard even an enemy accuse him of intentional dishonesty or corruption." After Lincoln's assassination, Rev. Hale officiated at his burial service in Springfield on May 4, 1865. Other clergy delivered the address and benediction, but Hale opened the ceremony with a prayer. The news of Lincoln's assassination on April 14, 1865, had reached New Haven the following morning by telegraph. All businesses closed, the church bells tolled, and a public meeting was held at noon at the steps of the State House on the Green in front of the Old Brick Row of the Yale campus. Rev. Leonard Bacon led the meeting in prayer. The Yale Literary Magazine, the only student journal at the time, published a tribute that concluded with these words: "But amid all our grief we have some consolations. His death was not in vain. . . . It awakened all men to a proper estimation of the virtues of Abraham Lincoln, and inspired all with a spirit of investigation into the life and character of a truly great man."

The comment period has expired.

|

|