loading

loading

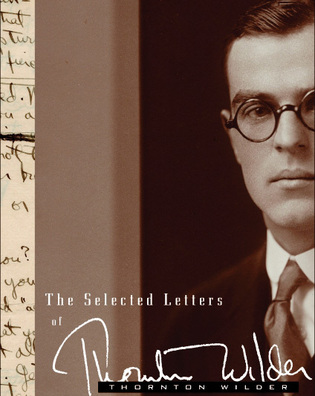

Arts & Culture"Ever thine, Thornt"Mark Blankenship '05MFA, a theater critic and reporter, writes for the New York Times and Variety.  View full imageOn November 18, 1975, Thornton Wilder ’20 wrote to thank the critic Malcolm Cowley, who had just written a scathing review of an unauthorized biography of the eminent playwright. Wilder was 78, recovering from prostate surgery, going blind from hypertension, and enduring the constant pain of a slipped disk. He had less than a month to live. He had to have known he was on his way out. But he wrote as if he had ages in front of him: "Dear Malcolm, I shall always be grateful to you." Even in a letter from December 3, written just four days before he died, Wilder pleasantly recounts his day, commenting on the weather and current films. The closest he gets to self-pity is a quick admission that "recent setbacks have taken a lot of energy out of [him]," followed up with the sunny assertion that he's plotting a new piece of writing. That's a tough, relentless kind of optimism. It girds nearly all of the 336 entries in The Selected Letters of Thornton Wilder, a collection of his correspondence that spans his entire life. Edited and annotated by scholars Robin G. Wilder and Jackson R. Bryer (the former is Wilder's niece by marriage), the book presents its subject as a man who brooks no complaining, passionately loves his friends and family, and approaches even terrible situations with a generous heart and clever pictures in the margins. The collection makes Wilder seem like an especially winning character in a Thornton Wilder work. A letter to the distraught composer Louise Talma insists, "None of us escape suffering, but let us be sure we suffer about essential things. You have made me suffer at the spectacle of you in great distress over an emotional imagined situation of your own making." That statement, with all its affection and impatience, may as well come from George Antrobus in The Skin of Our Teeth. Like the Wilder of these letters, Antrobus acknowledges the world's harshness, but he refuses to let it take precedence over essential things like poetry, family, and philosophy. Bryer and Robin Wilder deserve credit for crafting such a coherent portrait of a man who never wrote an autobiography and was loath to discuss his personal life. Along with the letters, they include copious footnotes and several thorough biographical essays to supply details that Wilder himself doesn't discuss in correspondence. With one notable exception, their additions create an excellent balance of things said and unsaid, allowing the writer to emerge as complex and knowable. Only Wilder's love life gets redacted on both fronts. His homosexuality and brief relationship with the writer Samuel Steward are now widely accepted, yet they are absent from these letters, and aside from an oblique reference in Scott Donaldson's foreword, they are scrubbed from the notes and essays. For Wilder's correspondence, the silence makes sense. He barely writes about his beloved mother's death or his sister Charlotte's mental collapse, so it's no surprise he skips over sex. The editors, however, have no reason to be so discreet. Since they counter his chipper final letters with the stark realities of his illness, why can't they contextualize his many letters to Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas with a note that references his own purported loves? This troubling omission narrows the scope of an otherwise broad and illuminating book. Of course, the collection doesn't have to be read as a personal portrait at all. Even people hungry for celebrity gossip will be rewarded on every page. There are intimate letters to Mia Farrow, Ernest Hemingway, Laurence Olivier, Gene Tunney, and Ruth Gordon. There are accounts of roller-skating with Walt Disney and collaborating with Alfred Hitchcock. There's even the delicious shock of Wilder's 1933 letter to the critic Alexander Woollcott, raving about a teenager he met in Europe named Orson Welles. There are also letters that are juicier in hindsight. For instance, anyone who's used to Edward Albee's status as the lion of American drama might chuckle when Wilder scolds the young writer for The Zoo Story, which the elder playwright deems another "chance encounter" play whose "form is tired old grandpa's." It's also fascinating to realize how many projects Wilder turned down. What if he had allowed Leonard Bernstein to make an opera out of The Skin of Our Teeth or had accepted Hollywood's offer to write a picture for Greta Garbo? It's possible the world lost a few masterpieces; at least it gained some cleverly worded letters explaining what might have been. Then there's what might be: Wilder and Bryer include several of Wilder's letters about how he sees his own plays, which should be required reading for anyone planning a revival. Take this prayer he wrote for a British director of Our Town: "God grant you can find an actress who can say Emily's farewell to the world not as 'wild regret' but as love and discovery." If future artists heed that kind of advice, they can capture the vigorous spirit of Wilder's life and work. Somewhere, Wilder will no doubt be grateful.

The comment period has expired.

|

|