loading

loading

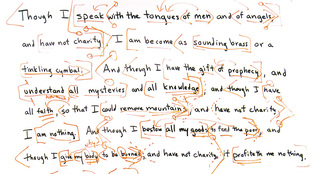

Arts & CultureObject lessonThe actor's work Evan Yionoulis ’82, ’85MFA, is an adjunct professor in the Department of Acting at the Yale School of Drama and a resident director at Yale Repertory Theatre.  Mark Zurolo ’01MFAOn a drama school whiteboard, director Evan Yionoulis ’82, ’85MFA, outlined how an actor should read a text—in this case, 1 Corinthians 13:1–4. View full imageAn actor finds clues to character, need, and intent not only through the circumstances laid out in the story of a play, but also in the play's language. In homework and rehearsals, through an experiential process both physical and imaginative, the actor works to get the language into his body, make it his own. First, however, she has to unlock its syntax and image structure to discover what there is to be embodied. This is true with every piece of dramatic writing, but with Shakespeare, for example, and other material with heightened text, sometimes that structure is not immediately apparent. Paul's First Letter to the Corinthians, Chapter 13, was a passage used by David Hammond, a professor of mine when I was a student at the School of Drama, to teach text work. Because of its familiarity and its beauty, and with thanks to him, I use it with my students there today. So, imagine that our character is speaking these words. Before we investigate who "Paul" might be, to whom he is speaking, what he wants from them, let's look at the text, uncover its argument, and examine its images. To begin, we use a process not unlike sentence diagramming. We identify the subject (the second "I") and the complete verb phrase and place the latter in brackets: [am become as sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal]. The dependent clause <Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels and have not charity,> has its own subject "I." We mark its two verb phrases and the prepositional phrases within, identifying what they modify. We notice the long vowel sounds of "sounding brass," the short ones of "tinkling cymbal." We mark the entire passage, examining the relationships between thoughts, noticing repetitions. The first three sentences are structured in this way: <Though I [do or have a thing], and have not charity,> there is this consequence. After it has been once introduced, "have not charity" need not be stressed. The newly appearing images -- what "I" might do or have, and the consequences -- are now operative, that is, they carry the action of the text. Through these images, the passage builds forcefully. If I have not charity, then, even though I understand all mysteries, and not just all mysteries, but also all knowledge, and even if I have all faith -- enough to move mountains! -- I am nothing. (Nothing: less even than a tinkling cymbal.) And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor and give my body to be burned -- say it aloud and note the repetition of the "b" and "g" and "d" sounds -- and have not charity, as I said before -- not only am I nothing, but it profiteth me nothing. The text asserts its own music, its own urgency, communicates its own necessity, and this is what the actor works to allow to come through. There's so much more. But as on the day the text was jotted on this whiteboard, we'll have to save the rest for another session.

The comment period has expired.

|

|