loading

loading

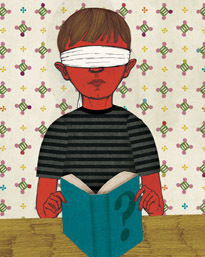

ForumThe truth about learning to read wellE. D. Hirsch Jr. ’57PhD is the author of Cultural Literacy (1987) and The Knowledge Deficit (2006) and founder of the nonprofit Core Knowledge schools. This essay is adapted from his forthcoming book, The Making of Americans: Democracy and Our Schools, which critiques the civic and social goals of U.S. schooling.  Barry FallsView full imageAmple research shows that scores on fill-in-the-bubble reading tests are the most reliable predictors of Americans' future economic status and ability to become effective citizens. Reading ability embraces multiple skills one needs in order to become effective in the public sphere. From the ability to understand strangers and make oneself understood in turn, other competencies flow. One can learn new things readily, prosper in school, and possess the general knowledge needed to train for a new job. No Child Left Behind reasonably places a big emphasis on reading tests, but that has unfortunately accounted for the unintended consequence that much time is being misspent on how-to skills and test preparation. Yet the fault lies not with the tests but with the school administrators who have been persuaded that it is possible to drill for a reading test. Summarize, classify, and find the main idea: the bulk of time in early language-arts programs today is spent practicing these and other abstract strategies on an incoherent array of uninformative fictions. Ever since this cramming has been put into effect, reading scores in later grades have trended downward, because the cramming has driven out the very thing -- coherent content -- that could enable children to ace their reading tests. Reading comprehension is not a universal, repeatable skill like sounding out words or throwing a ball through a hoop. “Reading skill” is rather an overgeneralized abstraction that obscures what reading really is: an array of separate, content-constituted skills such as the ability to read about the Appalachian Mountains or the ability to read about the Civil War. The specific knowledge dependence of reading tests becomes obvious in those given in the later grades. Here is a passage from a tenth-grade Florida test:

The origin of cotton is something of a mystery. There is evidence that people in India and Central and South America domesticated separate species of the plant thousands of years ago. Archaeologists have discovered fragments of cotton cloth more than 4,000 years old in coastal Peru and at Mohenjo Daro in the Indus Valley. . . . Today cotton is the world's major nonfood crop, providing half of all textiles. In 1992, 80 countries produced a total of 83 million bales, or almost 40 billion pounds. Much tacit knowledge is needed to understand this passage. It would help to have an idea of how cotton grows and how it is harvested and then put into bales. (What's a bale?) It would help to know that the Indus Valley is many thousands of miles from Peru. (How many tenth graders know that?) Then consider the throwaway statement that different people “domesticated separate species of the plant.” Ask a group of tenth graders what it means, and chances are that most will not know. They will not understand that part of the test passage, no matter how well they can perform the tasks currently taught in language-arts classes.

This passage illustrates the way reading comprehension works. The writer assumes that readers know some things but not others. In this case, readers were not expected to know how long human beings have used cotton -- the new information supplied in the passage. That is exactly how a school textbook or the Internet offers new information: it is embedded in a mountain of taken-for-granted knowledge. That is the way language always works. I once wrote a short piece for Education Week in which I offered a mock reading test chosen from one of the most influential books ever written, Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. It included sentences such as: “A manifold, contained in an intuition which I call mine, is represented, by means of the synthesis of understanding, as belonging to the necessary unity of self-consciousness, and this is effected by means of the category.” I invited the readers of Education Week to apply the strategies they compel children to practice: summarize, classify, and find the main idea. Most, I suspect, were still clueless. A reading test is inherently a knowledge test. Hence the tests are unfair to students who, through no fault of their own, have little general knowledge. Their homes have not provided it, and neither have the schools. I therefore propose a policy change that would at one stroke raise reading scores, narrow the fairness gap, and induce elementary schools to impart the general knowledge children need. Let us institute curriculum-based reading tests in first, second, third, and fourth grades -- that is to say, reading tests containing passages based on knowledge that children will have received directly from their schooling. To carry out this idea, the education department of a state will need to announce something like the following: “Here is the specific core curriculum that students should learn in the first five grades. For the next five years our reading tests for each grade will contain passages from domains taken from that coherent curriculum: such as Greek and Roman myths, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 'Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves,' 'The People Could Fly,' the geography of the Mediterranean Sea, Julius Caesar, the Hopi and Zuni Indians, Ponce de Leon and Florida, Canada, the Thirteen Colonies before the Revolution, the speed of light, sound and the human ear, and the solar system.” At the same time that the state made this announcement it would also make available the materials and professional guidance teachers would need to teach those topics effectively. All topics the state mentioned would likely be taught. Tests would continue to drive schooling -- as always -- but they would do so in an educationally productive way. Offering children a good education is the right way to cram for a reading test.

The comment period has expired.

|

|