loading

loading

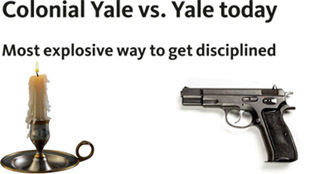

Arts & CultureBack in the dayCathy Shufro teaches writing to twenty-first-century undergraduates at Yale.  Photo illustration: Mark Zurolo ’01MFAView full imageFor the first day of History 115, The Colonial Period of American History, Professor John Demos likes to describe life at Yale in the early eighteenth century. This article is based on his lecture. It’s 1730, maybe 1735, and you’ve just arrived at Yale College. Apparently you aced the admissions interview, conducted wholly in Latin and Greek. You’ve sized up the campus, just a single sky-blue building, and you’ve stacked wood beside the fireplace in your chamber. You’re a man, of course; women won’t be admitted for another couple of centuries. And you’re not only a man but a gentleman, as annual tuition comes to £25 ($5,000-plus in twenty-first-century terms). There are no scholarships on offer, no FAFSA forms to fill out, no work-study jobs. To get here, circa 1730, you “prepped”—not at Andover or Harvard-Westlake—but with a minister. You’re most likely the son of a minister yourself, as such young men dominate the incoming class of 15 or 20 students. Your father might conceivably be a merchant, however, or a sea captain or prosperous farmer. You’ll learn quickly who’s who, because rank is everywhere apparent. You march in rank order, and you sit in rank order in class, at meals, and in chapel. Although good scholarship or character can boost your rank, being the governor’s son is the best guarantee of first place in line. Misbehave, and you may be “degraded,” or “put down.” If you have any gumption, you’ll risk that by pulling pranks. You might, for instance, surreptitiously herd a few sheep into the chapel, or replace candlewicks with fuses that cause small explosions during prayer, or tuck some ducks under the pews. A small transgression might lead to a public scolding, or “admonition.” Do something more serious, and your rank might be degraded. You could be suspended, or worse, expelled. (This will happen to a fellow who fornicates with a local “damsel,” even though he marries her.) Your library books offer opportunity for transgression as well. One student will write in the margin of his textbook: “Mr. Calvin Chapin is an old hypocrite and a whoremaster, too.” Your day begins when the college bell rings at 6 a.m., and breakfast is bread and beer. Everyone must be in his room at 9 p.m. Candles out at 11. No rekindling allowed before 4 a.m. Despite the parochial standards of students’ daily lives at Yale, there is still room for debauchery. As a Yalie undergraduate recounts, he and his cohorts concocted a beverage of six quarts of rum, two pails of cider, and eight pounds of sugar, and proceeded to enjoy “so prodigious a rout that we raised the tutor.” Next stop: a local tavern. As they say, the more things change . . .

The comment period has expired.

|

|