loading

loading

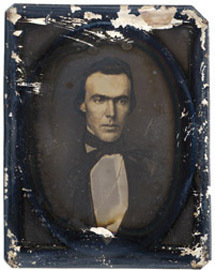

Old YaleYale alumni in the Gold RushJudith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  Manuscripts & ArchivesAustin Arnold, Class of 1848, spent less than a year in California and died of consumption shortly after returning home. View full imageIn 1891, Century Magazine published a series of letters written by Roger Sherman Baldwin Jr. ’47 about his journey to California as a forty-niner. “In the last days of 1848,” the article explained, “a number of young Yale graduates, bound together by almost brotherly friendship and the intimate association of long years of school and college life, were suddenly seized with a longing to join the throng that from all parts of our country was working its way by every known and unknown route to the newly discovered gold-fields of California.” The Yale alumni who became forty-niners recorded their experiences in essays and letters home, many of which are preserved in the Beinecke and Sterling Memorial libraries. In a December 1849 account of California life, which was published the next May in the Hartford Courant, George G. Webster ’47 wrote of “pitching our tent at night—carpeting with rubber blankets—making our own flapjacks, boiling our own hasty pudding, and ‘frying our own fish,’ a noble salmon of 20 lbs, just drawn from the cold and rapid American Fork, as we passed along its banks.” He added, “Don’t you wish you were in this magnificent country!” For Yalies born and bred in the East, the West was awe-inspiring. Baldwin was one of many who came from old New England families. (One of Baldwin’s great-grandfathers, Roger Sherman, was a framer of the Constitution and served as a treasurer of Yale.) In February 1850 he wrote to his sister, “Any one of the thousand canons that cross the country has sides as high & as steep as East Rock. . . . California is of all sorts—In the South an Italy, in the North a Norway.” Baldwin was as astounded by Wild West culture as by its landscape. On October 7, 1849, three days after arriving in San Francisco, he wrote to his family, “Such another city never was and never will be. Sharpers, swindlers, speculators, gamblers, and rogues of every nation, clime, color, language, and costume under the sun are here gathered together, and no words can convey a true idea of the result.” Most of the Yale forty-niners no doubt expected to enter professional life eventually; Baldwin, for one, had gone west to seek his fortune in practicing law as well as in mining gold. The forty-niners of the Class of 1847 sent a “California Letter” to their 1850 class reunion that read, in part:

As for success in life, we are all well satisfied. The crowd has made a “right smart sprinkling of dust,” though money has not been the chief object of our pursuit. We all are determined to take the pleasurable novelty of this roving life, and thus far have succeeded. The cup is not yet out nor do we begin to taste of the dregs. How long it will be before we settle down into quiet, respectable burghers, none of us can foresee, but sometime in the next 50 years we hope to assume that character. But the mining life was perilous, and not all survived it. Baldwin lost his valuable law library in a fire. In the fall of 1856, he was thrown from his horse and struck his head on a stone, and he died at Baker’s Ranch of “brain fever” at the age of 30.

Another who found an early grave was Josiah Savage ’46, who died of fever induced by exposure and fatigue at the mines in November 1849; he was buried under a pine tree on the banks of the Trinity River. Some may have been brought down by the trip itself, a grueling three to five months by ship. Austin Arnold ’48 arrived in San Francisco in September 1849, left the next May, and died of consumption in Connecticut that August. His classmate Cyprian G. Webster stayed only a month in San Francisco. By his own account, he “returned a wreck,” in the spring of 1850; he died of consumption in Mobile, Alabama, in October. But many prospered. George G. Webster became a gold-dust buyer and banker, an agent of Wells, Fargo & Co., and a money- and stockbroker in San Francisco. Henry H. Haight ’44, a lawyer from St. Louis, was elected governor of California in 1867. Today, he is memorialized in San Francisco in Haight Street and the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Among the older generation of Yale forty-niners was Sherman Day ’26, the son of Yale president Jeremiah Day and grandson of Roger Sherman. Failing finances led him to start over as a civil and mining engineer in California. The Massachusetts clergyman and academic Henry Durant ’27 founded the College of California in Oakland and served as its first professor. In 1868, the College of California merged with the state’s land grant college to become the University of California. Haight signed the act that created the university, Day was a founding trustee and professor, and Durant became its first president. Its second president was another Yale alumnus, the geographer Daniel Coit Gilman ’52. It is no coincidence that the colors of the University of California are gold and Yale blue.

The comment period has expired.

|

|