loading

loading

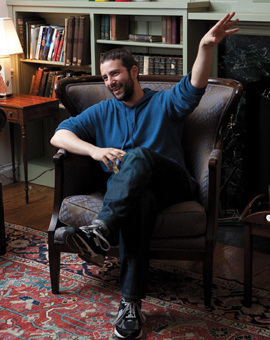

featuresThe WunderkindOut of works built from his inner fears, a 32-year-old playwright stages an extraordinary rise. Julia M. Klein is a Philadelphia-based cultural reporter and critic and a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review.  Julie BrownItamar Moses ’99 at a Davenport College master's tea in December 2009. View full image“Yes, astonishing, isn’t it? And at his age.”—Georg Balthasar Schott, an organist in Bach at Leipzig, on the talent of the titular character In lieu of fixing a meeting place for lunch, Itamar Moses ’99 told me to telephone when I arrived in his Brooklyn neighborhood. I emerged from the subway station in Park Slope to a disorienting jumble of cafés and shops. When I called, he said he would leave his brownstone and we’d walk toward each other along Seventh Avenue. We would meet somewhere along the way. I wasn’t at all sure his plan would work. The thoroughfare was crowded, and the only image I had ever seen of him was several years old. Moses had no idea at all what I looked like. But as it happened, I had no trouble picking him out from across the street. Dressed in blue jeans and a gray shirt, he cut a youthful and somewhat quizzical figure as he cocked his head to the side looking for me. Both the unusual gamble and his inquiring look would come to seem characteristic. At 32, Itamar (EET-a-mar) Moses is a theatrical wunderkind, though he professes not to regard himself that way. “I sort of think it’s the case that nobody knows who I am,” he told me over a bowl of corn chowder. That is likely to change. “One might reasonably conclude that this is . . . the time for this ambitious young playwright-as-thinker, already beloved of theater insiders, to break through to a wider audience,” Rob Weinert-Kendt wrote in the Los Angeles Times in September 2008. “It’s clear this is Moses’s moment,” Mark Blankenship ’05MFA declared a month later in American Theatre magazine, citing productions at such prestigious venues as the Manhattan Theatre Club and Berkeley Repertory Theatre. When a set of linked one-acts, titled Love/Stories (or But You Will Get Used to It), opened in early 2009 at the Flea Theater in Tribeca, the Wall Street Journal’s theater critic, Terry Teachout, was moved to exclaim: “Is there anything he can’t do?” Moses’s development as a playwright has been rapid, telescoped. “He has a mind that’s very acutely tuned to structure, and he has an amazing ear for dialogue. It’s unusual to have a playwright who is so strong in both of those,” says Daniel Aukin, who directed the 2008 MTC production of Back Back Back, Moses’s take on steroids in baseball. One of his early plays, Outrage, was a dramatization of his Yale senior thesis. Another, Bach at Leipzig, earned comparisons (not always favorable) to Tom Stoppard. After these ambitious and prolix historical riffs, Moses unexpectedly unveiled more refined and modestly scaled work: chamber pieces, such as The Four of Us and Back Back Back, both of which examine ambition through the prism of friendship. Ambition has been a “central preoccupation,” Moses says. But these days he is moving toward a new focus, on romantic love and emotional commitment; and new formal challenges, including musical theater and screenplays. Over time, he has learned to expend less effort on verbal pyrotechnics—to strip down his work and risk simplicity instead. Moses’s personal struggles have always filtered into his writing, but now they lie closer to the surface. “You write about feelings that, while locked up inside of you, are really terrifying or overwhelming,” he says. “When you write about this stuff, you take the power it has over you in your life, and you put that power into your work.”

|

|