loading

loading

Arts & CultureYou can quote themYale law librarian Fred R. Shapiro is editor of the <i>Yale Book of Quotations</i>.

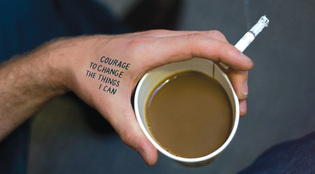

Photo illustration: John Paul ChirdonView full image

Readers of this column know that I have been studying the “Serenity Prayer”—the most famous and beloved of all modern prayers—for some time. In this magazine, I’ve written primarily on its authorship (most recently in January/February, concerning new evidence that the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr ’14BDiv, ’15MA, was indeed the likely originator). But questions have also been raised about its wording. Specifically: did Alcoholics Anonymous “dumb down” the Serenity Prayer? Much of the prayer’s worldwide popularity is due to AA. In the mid-twentieth century, AA adopted the prayer as a part of its culture of recovery, and it remains a mainstay today. AA’s version runs as follows: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; the courage to change the things that I can; and the wisdom to know the difference.” Reinhold Niebuhr’s family, however, prefers a different text: “God, give us grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, courage to change the things that should be changed, and the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other.” His daughter Elisabeth Sifton, in her book The Serenity Prayer(2003), presents this “grace” text as her father’s preferred version. In the book, she roundly criticizes AA for modifying the prayer. “Their version frames the prayer in the first-person singular,” she notes. It also “omits the spiritually correct but difficult idea” of praying for grace. And furthermore, “courage to change what should be changed becomes, in the AA rendering, simply courage to change what can be changed.” She adds: Goodness me, just because something can be changed doesn’t mean that it must be! More important, … there are circumstances that should be changed yet may seem beyond our powers to alter, and these are the circumstances under which the prayer is most needed. The shift in the text reduces a difficult, strong idea to a banal, weak one, and I suspect that this dumbing down of the prayer has contributed to its enormous popularity. Niebuhr did use the family’s preferred “grace” version in a 1984 article, published posthumously with a note that it dated from 1967. And “grace” may have had a long pre-1967 history in his unpublished use. Yet there is strong evidence that Niebuhr also used a version much like AA’s. Family accounts agree that he delivered the prayer in a church service in Heath, Massachusetts, in 1943, and afterward gave a copy to a neighbor. Sifton assumes in her book that the 1943 prayer was the family’s preferred version. However, the neighbor, Howard Chandler Robbins ’99BD, had asked permission to include Niebuhr’s prayer in his Book of Prayers and Services for the Armed Forces. The text he printed reads: “Give me the serenity to accept what cannot be changed, / Give me the courage to change what can be changed— / The wisdom to know one from the other.” This prayer uses first-person singular; it omits “grace”; and it asks for courage to change “what can be changed.” Clearly, these elements cannot be credited to or blamed on AA. But there is a still earlier formulation, printed in 1937 in a religious periodical and attributed to Niebuhr. It reads, “Father, give us courage to change what must be altered, serenity to accept what cannot be helped, and the insight to know the one from the other.” This version lacks the idea of “grace,” but otherwise has the elements Sifton and her family prefer. And it asks for courage before serenity, which seems fitting for a theologian whose life embodied great courage on many levels.

The comment period has expired.

|

|