loading

loading

Arts & CultureObject lesson"Pavlov's beef-steak" John Harley Warner is the Avalon Professor of the History of Medicine at the Yale School of Medicine. His most recent book is Dissection: Photographs of a Rite of Passage in American Medicine, 1880–1930.

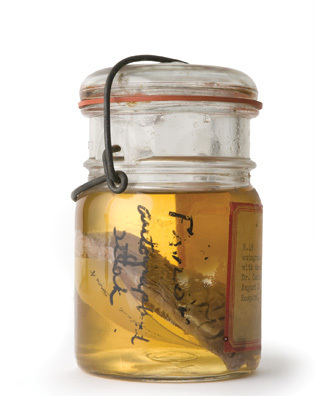

Mark MorossePhysiologist Ivan Pavlov inscribed his name on this piece of beef while trying out an electrosurgical knife in 1929. Dr. Harvey Cushing, Class of 1891, gave it to Yale. View full image

It is the only wet specimen in the room, on a high shelf just above eye level. The rest of the room—the Cushing Study, a small office off the Medical Historical Library in Yale's Sterling Hall of Medicine—is filled with books, diaries, and memorabilia. The printed label on the jar reads "Cushing Tumor Registry," but this is a souvenir rather than a pathoanatomical specimen. Typing on the label tells us that "this is a piece of steak autographed by Ivan Petrovitch Pavlov."

This modern reliquary, like its medieval predecessors, has little meaning apart from the story attached to it. In mid-August 1929, the Harvard Medical School hosted the Thirteenth International Physiological Congress, one of the largest gatherings of scientists ever convened in the United States. Pavlov, the doyen of experimental physiology at almost 80 and honored by a Nobel Prize a quarter-century earlier, was the lion of the gathering. His pioneering work on conditioned reflexes had been crucial to understanding brain function, and he was keen to see the Harvard neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing '91 operate. The preeminent brain surgeon and father of modern neurosurgery as a field, Cushing, two decades younger than Pavlov, was at the top of his game. Performing for Pavlov in a theater at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Cushing removed a large tumor of the left hemisphere from a cancer patient's brain. The patient later recalled that Cushing introduced him to Pavlov, saying, "You are now shaking hands with the world's greatest living physiologist." Pavlov was captivated by the new electrosurgical knife Cushing used in the operation, and at the end of the procedure, Cushing got a piece of beef so that the elder scientist could try his hand. After making a few incisions, Pavlov inscribed his name into the meat. "I asked him whether he wanted me to eat the meat in the hope of improving my conditional reflexes," Cushing wrote in his journal, "or whether we could keep it in the museum, the latter we will proceed to do—'Pavlov's beef-steak.'" A collector of old medical books and of brain tumors, when he died in 1939 Cushing bequeathed both to Yale, where his rare books would become the cornerstone for creating the Medical Historical Library. The passage of time has largely eroded Pavlov's autograph from this lump of meat. Nothing is to be learned—or, really, ever was—from the specimen itself. But for Cushing, as for many elite physicians of his generation, portraits, mementos, and above all books provided connections to the past, a source of identity in the present, and a means of culture. Cushing relished the dramaturgy of professional life and reveled in commemorating scientific culture. "The only grievance I have against my friends, the physiologists," Cushing reflected privately in his journal after the Congress, "is that they have no histrionic sense." He bemoaned the missed opportunity to have had a "moving picture camera" capture Pavlov at the lectern, creating "a record worth preservation." What remains in the specimen jar is a site of memory, a vehicle for imaginatively recalling the encounter between Pavlov and Cushing and the creation of a relic.

The comment period has expired.

|

|