loading

loading

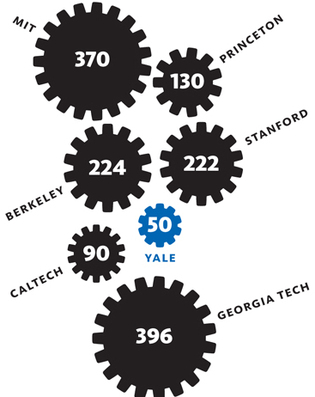

Light & VerityEngineering a comeback Mark Zurolo ’01MFAYale’s engineering school has significantly fewer full-time faculty than the leading programs. View full image

In a set of organizational changes approved over the summer, the School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS) seems to be going in two directions at once. Despite curbs on faculty growth throughout the university due to the economic downturn, SEAS has been given approval by the Yale administration to increase its number of faculty slots by more than one third over the next few years. But before it embarks on that ambitious project, the school will shrink significantly, losing the applied physics department and its 12 faculty. The school has also moved the environmental engineering program into its chemical engineering department. The policy was adopted after a rough-and-tumble review process that began last year. SEAS dean Kyle Vanderlick explains that the changes would help the school focus on its core engineering disciplines and “position us for the growth we need to become more competitive. When you compare us to the powerhouse engineering schools, our departments are totally undersized. We’re what you'd call ‘subcritical.’” With applied physics no longer in the mix, SEAS has about 50 full-time professors, evenly distributed in four departments. A typical school would have at least 100 faculty, says Vanderlick. "We're simply stretched too thin." In pushing for the reorganization, Vanderlick's goal is to make SEAS "the exemplar of Ivy engineering." One key component of the plan, she says, is to focus on four interdisciplinary research themes—biomolecular engineering and biodesign; energy and sustainability; sensing, imaging, and networked systems; and surface and interfacial engineering—that will help link the four engineering departments and enable SEAS to excel in specific areas of national importance. When Vanderlick and the Yale administration unveiled a draft reorganization proposal to SEAS faculty in February, many faculty were surprised and dismayed by the loss of applied physics—and by a proposal to dismantle the chemical engineering department, by parceling out its faculty members to the remaining departments. After considerable back-and-forth, an agreement was reached on the current configuration, with applied physics spun off as a stand-alone department and chemical engineering in a department with environmental engineering. As for applied physics, Paul Fleury, an applied physicist and Vanderlick's predecessor as engineering dean, says he and his colleagues almost immediately opted out of any fight to remain in SEAS. "Independence is fine," says applied physicist Daniel Prober. "We see July 1 as our Independence Day." Electrical engineering and applied physics professor Mark Reed says he's "excited by the possibility of increasing by about 20 positions over the next decade." But Reed, like Vanderlick and other SEAS faculty members, is quick to point out a huge impediment to implementing the plan: "We have no space for expansion." A new engineering building has been proposed (for the old Yale Health Plan site on Hillhouse Avenue) but it is currently on hold. "We've laid the groundwork for the future," says Vanderlick. "But the path is not yet obvious."

The comment period has expired.

|

|