loading

loading

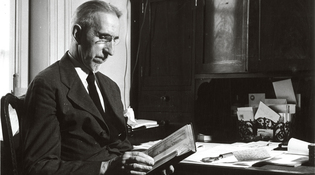

Old YaleMidlife career change Manuscripts & ArchivesAnson Phelps Stokes, Class of 1896, was Yale University Secretary for 22 years. In his post-Yale role in the Episcopal Church he championed civil rights causes and helped arrange Marian Anderson's 1939 concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. View full image

In many ways, Anson Phelps Stokes (1874–1958) exemplified his era’s ideal of the Yale man. Born of a wealthy New England Protestant family, he attended Yale College and spent much of his career as a Yale administrator. Yet his life also reflects changes both in Yale and in the nation. Stokes was an Episcopal priest, and by 1921 Yale had moved sufficiently far from its religious origins that his ministry was an obstacle to his otherwise brilliant career prospects. He then went on to a second career in the church and became a champion of civil rights causes, notably the effort against the segregationist policies of the Daughters of the American Revolution. A graduate of the Class of 1896, Stokes was named after his father, a leading banker and philanthropist. One of their homes—Shadowbrook, in Lenox, Massachusetts—had 100 rooms and was the largest house in America in the 1890s. When Stokes was an undergraduate, the story goes, he once telegraphed his mother that he would like to bring “some ’96 fellows” up for the weekend. She replied, “Many guests already here. Have only room for 50.” After graduation, Stokes attended the Protestant Episcopal Theological Seminary in Cambridge. He was appointed secretary of Yale when he was only 25. He would serve for more than two decades, from 1899 to 1921, transforming a relatively minor job into a major administrative post; today, the secretary is widely considered the third most important university officer after the president and provost. Stokes instituted modern record-keeping systems, developed the present system of relations between Yale and the alumni, and secured the university’s first large endowment gift. In Stokes’s view, his major accomplishment as secretary was securing Science Hill for the university. In 1905 he saw an opportunity to purchase Sachem’s Wood, a 60-acre tract owned by the James Hillhouse family. He was convinced that Yale needed more land for further growth, he wrote later, but Yale’s board of trustees “felt poor and was not sufficiently appreciative of [the land’s] value to take the initiative to provide the funds.” With President Arthur Twining Hadley’s approval, he proceeded to negotiate. In the end, a single donor gave the entire cost of $650,000. Stokes came close to assuming the presidency of Yale: he had Hadley’s backing and substantial support on campus. But others opposed a return to the old Yale tradition of a minister as president. The trustees deadlocked in the preliminary ballot, and James Rowland Angell, a dark-horse candidate, won the post. Stokes’s career in the Episcopal Church began in 1924, when he became canon of the Washington National Cathedral in DC; he served until his retirement in 1939. He became a leading advocate of social reform efforts in the city, often enlisting the support of Eleanor Roosevelt. His papers at Yale contain many letters from national African American leaders, including Booker T. Washington, activist and educator Mary McLeod Bethune, and W. E. B. Du Bois. In 1928, Stokes faced his first confrontation with the Daughters of the American Revolution over “interracial matters.” An Episcopal Church convention had been scheduled on DAR premises, but the DAR refused to accommodate one of the meetings because its program included African Americans. Stokes had to negotiate with the DAR’s president general for an exception to the rule. In 1939, Howard University tried to book a concert in the DAR’s Constitution Hall by renowned contralto Marian Anderson. The DAR refused. Eleanor Roosevelt resigned her membership, and the issue became a national cause célèbre. Stokes was part of the Marian Anderson Citizens’ Committee, formed to lobby for a reversal. The campaign failed, but its efforts helped to produce a historic rallying point of the civil rights movement: Anderson’s Easter Sunday concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, before a crowd of 50,000. After the concert, Stokes published a pamphlet of the appeals he had written to the DAR. It concluded: “You may put your professional requirements for artists to appear in Constitution Hall as high as you like and we shall gladly respect them. Only we ask that art should recognize no color line.” Stokes stepped down in 1939 and devoted his retirement years to writing. In 1952 he received the Yale Medal, Yale’s highest alumni honor. His signature appeared on many Yale diplomas, the citation noted—and “is also on present-day Yale, of which he more than any man living is the architect.” The New York Times commented, after his death in 1958, “To the life of the American spirit, he made one of the great contributions of his time.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|