loading

loading

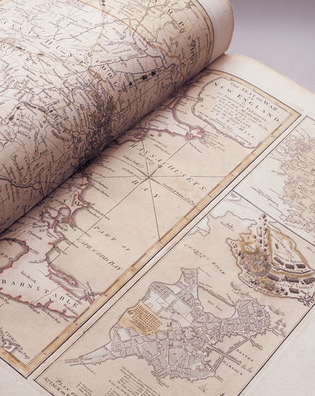

Arts & CultureObject lessonA president's maps Barnet Schecter ’85 is the author, most recently, of George Washington's America: A Biography through His Maps.  Mark MorosseThis map of the Massachusetts coastline includes a detail of the Battle of Bunker Hill (right, center). It was one of George Washington's personal maps, now housed at the Sterling Library Map Collection. View full image

When I first saw a reproduction of “The Seat of War in New England,” from George Washington’s map collection, I was immediately smitten. The stunning, vividly colored map combines cartography with detailed pictorial elements. In addition to charting the coastline, towns, and countryside of New England, the map dramatically depicts the early events of the Revolutionary War, including columns of citizen-soldiers converging on Boston to besiege the British after the clashes at Lexington and Concord; and Charlestown in flames during the Battle of Bunker Hill (right, center). I was eager to turn the pages and see what other marvels might be bound up in Washington’s personal atlas, now housed at Sterling Memorial Library. After a conversation with my longtime editor, I headed up to New Haven to see, in publishing parlance, “if there was a book in it.” My first book, The Battle for New York, had chronicled Washington’s seven-year struggle to defend and then recapture the city from the British, and my publisher had commissioned original maps to illustrate the major combat that tore through today’s five boroughs. But Washington’s personal maps presented a chance to view the Revolutionary War—and perhaps much more of his life—through his eyes directly. As I opened the atlas and proceeded to unfold some of these 43 large maps, I felt as if I were releasing the eighteenth-century atmosphere. On “A General Map of North America” (1762) by John Rocque, for example, the mapmaker noted in certain areas of northern Canada that “these parts are entirely unknown.” Here was an untapped primary source for George Washington’s life, a way to enter his world and experience it with all of the limits and the insights that shaped his outlook. Washington was deeply connected to the land, and maps were always central to his work; as a surveyor, landowner, military leader, farmer, and statesman, he drew and collected maps from his teens until his death. The ambitious young Virginia gentleman drew maps to secure the borders of his vast acreage on the Potomac River and in the West. After American independence, maps informed the broader vision of a mature leader, who viewed the sprawling new nation’s rivers as the key to unifying the states through commercial interdependence—even as the European powers predicted that the United States would soon be disunited, disintegrating into small, clashing, failed states. President Washington used his maps to conduct balance-of-power diplomacy and launch military campaigns in the borderlands against hostile Indian nations backed by Britain and Spain. Inspired by his trips to the frontiers and his study of the latest maps, Washington grasped the vast dimensions of the new nation and prophetically declared the United States “a rising empire in the New World.” An atlas, I found, can illuminate the story of a life.

The comment period has expired.

|

|