loading

loading

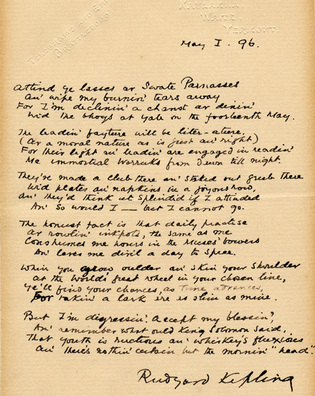

Arts & CultureObject lessonRudyard Kipling sends regrets David Alan Richards ’67, ’72JD, is an attorney, a noted Kipling scholar, and the author of Rudyard Kipling: a Bibliography (2010). He recently donated his collection of Kipling first editions and personal items to Yale.  Manuscripts & Archives"Mulvaney's Regrets" was Kipling's whimsical way of turning down an invitation to the Yale Kipling Club's annual banquet. The handwritten poem is now in Sterling Memorial Library. View full imageBy the mid-1890s, Rudyard Kipling was often called the most famous living writer in the world. So it is not surprising that a group of Yale sophomores founded a Kipling club in fall 1895. The next spring, they invited Kipling himself, then living in Vermont, to New Haven for the club’s first annual banquet. Instead of ignoring their letter, or sending a polite but nondescript refusal, Kipling responded with a poem. “Mulvaney’s Regrets,” as the verses came to be known, was couched in the Irish accent of Mulvaney, a character in many of Kipling’s stories. The club’s president, Gouverneur Morris Jr. ’98, read the verses aloud at the banquet. The “favorite phrase lay in the fourth line,” wrote club secretary Julian Mason ’98 some 50 years later: with that single phrase the bhoys at Yale, “we had been knighted and raised to the adult realm of literature.” The students quickly realized their literary hero’s verse could be published. They knew about Kipling’s deep resentment of unauthorized publication of his work (he once had 23 lawsuits going against pirate publishers at one time), but they showcased the poem in the Yale Literary Magazine regardless. Thus, the May 1896 Lit became a Kipling first edition. If Kipling knew, he showed no annoyance. In 1932, 36 years later, Mason was editor of the New York Evening Post. He found one day, to his horror, that the news editors had printed eight lines from another Kipling poem, without requesting Kipling’s permission. Within eight days, Mason received “an ominous-looking letter from a stately firm of New York attorneys.” He immediately sent a letter to Kipling, explaining that he was one of the “bhoys from Yale” and asking forgiveness. Sixteen days later, the attorneys dropped the claim for damages. In 1907, Kipling won the Nobel Prize for literature. But his reputation waned in the 1960s, as he was increasingly viewed as an unapologetic imperialist, says Professor Jed Esty of the University of Pennsylvania. Today, his work is being rediscovered, especially his masterly short stories. Still, besides The Jungle Book, Kim, and Just-So Stories, his work is little known in the United States. (The chorus of the “Whiffenpoof Song” was lifted from a Kipling poem, but few Yalies are aware of it.) Over the years, the Beinecke has acquired the largest collection of Kipling’s works of any library in the world. Last year, the Beinecke cemented its reputation as the premier venue for Kipling research when it acquired the archives of his literary agents. “Mulvaney’s Regrets” never made it into any official edition of Kipling’s work. He felt that as “a set of low Irish rhymes,” it was not to be considered part of the official canon. Nonetheless, the club’s faculty sponsor, Professor William Lyon Phelps ’87, remained appreciative. He wrote in 1939: “Perhaps no man of genius ever made a more gracious and generous response to an invitation from a college undergraduate.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|