loading

loading

Arts & CultureYou can quote them"Quotation magnets" Winston Churchill and Benjamin Disraeli Yale law librarian Fred R. Shapiro is editor of the <i>Yale Book of Quotations</i>.

Photo illustration: John Paul ChirdonView full image

In two previous columns, I’ve written about “quotation magnets”—people to whom memorable sayings are attributed inexorably, without regard for accuracy. Quotation magnet-ism is particularly prevalent in the political realm. Two preeminent examples are the British prime ministers Winston Churchill (1874–1965) and Benjamin Disraeli (1804–81). Below are some genuine quotes from each man (marked with a check) and some misattributed ones (marked with an x). Churchill: Real and Apocryphal Quotes

“Churchillian drift” is the term coined by Nigel Rees, editor of many quotations books, for the misattribution of grandiose or belligerent quotes to Sir Winston. The supposed exchange with Astor represents a different flavor of apocryphal Churchillism. George Thayer, research assistant for Randolph Churchill’s biography of his father, wrote in 1971 that the anecdote was false. And in fact, it’s an old joke. Barry Popik has posted on his engrossing site (BarryPopik.com) an extended 1899 version from the Colorado Springs Gazette, in which “a sour-visaged, middle-aged, fussy lady,” annoyed by a man smoking a cigar, delivers a variant of the poison line and receives a variant of Churchill’s supposed retort.

This supreme putdown of all overzealous grammarians was attributed to Churchill by Ernest Gowers in the 1948 book Plain Words, and today it is now always credited to Churchill. But in a thorough search, Garson O’Toole (pseudonym of a Yale ’86 PhD; his authoritative site is QuoteInvestigator) could find no such attribution before 1945. Then, following a lead from linguist Ben Zimmer ’92, O’Toole unearthed a 1942 version with no mention of Sir Winston, in The Strand Magazine: “When a memorandum passed round a certain Government department, one young pedant scribbled a postscript drawing attention to the fact that the sentence ended with a preposition, which caused the original writer to circulate another memorandum complaining that the anonymous postscript was ‘offensive impertinence, up with which I will not put.’”

Disraeli: Real and Apocryphal Quotes

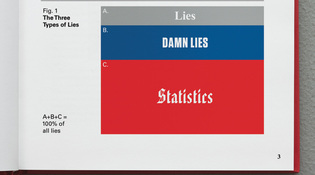

Until Churchill, Disraeli was unequaled as the quotable British politician. Mark Twain himself, in his 1906 autobiography, attributed the famous statistics line to Disraeli. In the Yale Book of Quotations, I documented the Disraeli attribution to 1895. Quotations researcher Stephen Goranson, however, has found several earlier variants, none attributed to Disraeli. The earliest, from 1885, referred to “experts” rather than “statistics.” The four earliest uses of “statistics” were all from 1891. Two were attributed to Charles Wentworth Dilke (1843–1911), and a third, unattributed, appeared in a publication Dilke owned and to which he contributed. For this reason, Goranson believes Dilke is a good candidate for originator of the “statistics” witticism. As it happens, Dilke himself was a politician, and it was once predicted he would become prime minister. But the first known use of the famous words “lies, damned lies, and statistics” was quoted in the Leeds Mercury, June 29, 1892. The source was a speech by Arthur Balfour—yet another prime minister.

The comment period has expired.

|

|