loading

loading

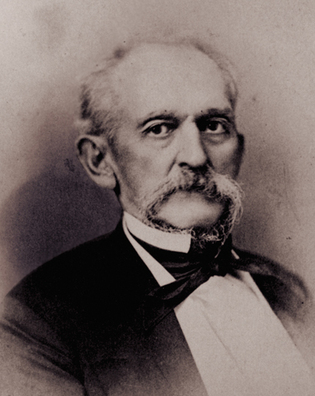

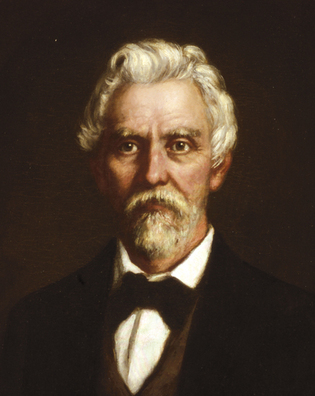

Old YaleThe Lone Star YaliesThe original Maverick, and other Yalies in the Texas Republic. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library. When US citizens flowed into Mexican Texas in the 1820s and early ’30s, at least three Yale graduates were part of the influx. Two of them would become founding fathers of the Lone Star Republic. Probably the first alumnus to go to Texas was John Punderson Austin of New Haven, Class of 1794. Two of his sons had followed the call of their kinsmen, Moses Austin and his son Stephen, to settle in Texas. (The city of Austin is named after Stephen, the “father of Texas.”) After one of John Austin’s sons died in the 1833 cholera epidemic, he went to Texas to manage the estate, but he too died of cholera, in 1834. His remains made the long journey home to New Haven for burial in the Grove Street Cemetery. The other two early Texas Elis were more fortunate: Ashbel Smith, Class of 1824, ’28MD; and Samuel Maverick, Class of 1825, whose name would enter the English lexicon.  Manuscripts & ArchivesAshbel Smith, Class of 1824, was briefly secretary of state of the Republic of Texas. View full imageAshbel Smith (1805–86), a Connecticut Yankee from Hartford, played key roles in the Texas revolution against Mexico and in the building of Texas culture and infrastructure. He arrived in Texas in the spring of 1837 and by chance became Sam Houston’s roommate. They became close friends, and Houston appointed him surgeon general of the Army of the Republic. Smith also served as a diplomat for the republic: in 1838 he negotiated a treaty with the Comanche Indians; in 1842–44 he served as chargé d’affaires to England and France (where he argued strenuously against Britain’s efforts to persuade Texans to abolish slavery); and in 1845 he became secretary of state—briefly, since Texas joined the United States late that same year. Smith was also the leading medical authority in Texas and a proponent of public and medical education. In 1881, as president of the University of Texas Board of Regents, he developed the faculty and curriculum needed for a first-class institution. Smith loved his life in Texas. In a letter (now in the Yale library) sent from his plantation, Evergreen in Galveston Bay, he wrote: “My health seemed to render it necessary for me to lead the outdoor, laborious, hearty existence of a plantation. It has agreed admirably with me; I am well tanned and in the New England phrase, ‘rugged as a bear.’”  Witte MuseumThe name of Samuel Maverick, Class of 1825, entered the English lexicon because of his unbranded cattle. View full imageSamuel Maverick (1803–70) came to Yale from South Carolina and returned to his home state after graduation to practice law. It is said that he left his law practice not long after a duel with a supporter of John C. Calhoun, Class of 1804, over Calhoun’s “nullification” argument—that individual states could withdraw their adherence to a federal law, as from a “compact,” if they thought it was unconstitutional. (Maverick’s Yale biography holds that the duel was with Calhoun himself.) Maverick managed an Alabama plantation before leaving for Texas in 1835. There he joined the Texas army under Stephen Austin; he narrowly escaped the Battle of the Alamo in 1836 because he was sent away to sign the Texas Declaration of Independence. After a long visit back in Alabama, he returned to Texas in late 1837 with his new wife and son, and several slaves, to settle there permanently. He served as mayor of San Antonio and later in the republic and state legislatures. Maverick’s greatest success was in land speculation. With nearly 400,000 acres in 30 counties, he became one of the wealthiest Texans of his time. The word maverick came into use because of Maverick’s unbranded cattle, which often wandered far from their herd. In 1889, his son George tried to correct the impression that Maverick was primarily a cattleman, and an irresponsible one at that. He wrote to the St. Louis Republic that his father had owned only a single herd, received in payment for a debt, and he blamed the negligent branding on an enslaved “colored family” left in charge of the herd when Samuel moved away. But the cattle connection has been forgotten by most people today who use the word maverick to refer to an independent thinker who refuses to conform—perhaps not that far off the mark for the man who had a duel over nullification and who left his state to become a Texas pioneer.

The comment period has expired.

|

|