loading

loading

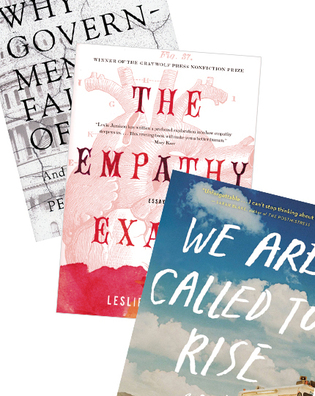

Arts & CultureReviewsBooks on empathy and on the problems with government.  View full imageWhy Government Fails So Often: And How It Can Do Better Thomas A. Smith ’84JD is a law professor at the University of San Diego. Peter Schuck has written a superb book on a dismal subject, Why Government Fails So Often. As the kids might say, the whole federal government seems one big fail. People have noticed. Over half of Democrats say government is broken. Sixty-four percent of everyone says big government is more of a threat than big business, and that’s after the most recent recession. Nearly 80 percent are frustrated or angry with government. That’s just the tip of the iceberg of the polling data Schuck cites. The problems with government are deep. It’s not partisan bickering or paralysis, which have been with us since Burr shot Hamilton, but something far more systemic, endemic, and pervasive. The bigger government gets, the more people dislike it. And it is big. On a per capita basis, Schuck says, the US public sector is bigger than in the UK, France, or Germany. Perhaps this wouldn’t matter if federal domestic programs worked, but they don’t. Digesting enormous literatures of evaluation, Schuck looks at programs on a cost-benefit basis. Why do they fail? Explanations are plentiful. Our political culture restrains policy effectiveness. Our constitutionalism sets rigid guidelines. Decentralization makes measurement difficult. Our tradition of individual rights makes policy implementation difficult. Interest-group pluralism renders government impotent. Our moralism, social diversity, populist suspicion of expertise, public opinion, and commitment to robust civil society all make the government elites’ job harder. Markets too—fast, diverse, inter-jurisdictional—are a fundamental impediment to public-policy success; if you don’t like a regulation, there’s probably a market waiting for you. And all that is only part of the bad news. Given the exhaustive detail and comprehensiveness of Schuck’s critique, one would expect him to give up. But he is a “militant moderate” and adds to his title And How It Can Do Better. He thinks that through incremental change good policy can be found, like Social Security, immigration reform in 1965, and airline deregulation in 1978 were—not perfect, but good. One key is good evaluation of policy, on which now only one dollar in one hundred is spent. Not political success but real success has to become the measure of good government.

The Empathy Exams: Essays Sylvia Brownrigg ’86 is the author of six books of fiction, most recently a novel for middle-grade readers called Kepler’s Dream. For the bright and provocative essayist Leslie Jamison, the capacious concept of “empathy” is a means of exploring pain, pride, and prejudice, and the ambiguous borders between oneself and other people. In this collection, which won the Graywolf Press nonfiction prize, Jamison seizes on occasions when a person’s pain has some inherent complexity: one long, disturbing piece chronicles the mysterious Morgellons disease, whose sufferers have (or imagine they have) parasites laying eggs under their skin but who tend to be viewed skeptically by doctors; “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain” looks at cutters, anorexics, and other self-afflicting females. It is discomfort, moral or physical, that triggers Jamison’s curiosity. She exposes herself even as she investigates others—looking unblinkingly at the “clattering machinery” of her own liberal guilt in touring a neighborhood blighted by gang violence, or comparing the relative lack of feeling she had in relation to her own abortion with what she went through having heart surgery. Although she exhorts herself, and by extension her readers, into sympathetic imagination of others’ predicaments, she is bracingly honest on the possibilities of self-congratulation in that project. She quotes a boyfriend who once called her a “wound dweller,” and questions her journalistic motives: “I wonder if my empathy has always been this, in every case: just a bout of hypothetical self-pity projected onto someone else.” Yet Jamison is a consistently intelligent and reflective guide, steeped in high culture (Edmund Burke, Alexander Pope) as well as low (MTV’s Real World, Cheez-Its). Occasionally her post-ironic convolutions veer into the obscure, or she turns slackly to Google searches to assist her cultural commentary, but at her best she is funny, compassionate, and sharply perceptive. Standouts in the volume include “The Empathy Exams,” her account of a job she once held enacting scripted illnesses to assist medical students in training, and “The Immortal Horizon,” a description of an extreme endurance run called the Barkley Marathons. In this vivid portrait of the loners, eccentrics, and former addicts who push their bodies to the excruciating limit, Jamison finds “evidence of a grace beyond the self that has, of course, come from the self.”

We Are Called to Rise: A Novel Melanie Asmar is a newspaper reporter and freelance writer based in Denver, Colorado. Stories about separate lives intertwining in unexpected, poignant ways, à la Crash or Love Actually, have come to be a literary standby. When it works, it really works. And when it doesn’t, the results can be strained. Laura McBride’s debut novel, We Are Called to Rise, is an example of when it works. The book is told from the perspectives of four different people: a woman whose marriage is falling apart and whose grown son hasn’t been the same since he returned from his last tour of duty in Iraq; a young soldier recovering from a suicide attempt; a woman who volunteers as an advocate for abused and neglected children; and an Albanian boy whose parents are struggling in America. That boy, eight-year-old Bashkim, who loves sharks and longs to play soccer, is the character who makes the story so captivating. As a reader, you care deeply about the perceptive child with the angry father, the loving but powerless mother, and the innocent little sister. Set against the backdrop of a Las Vegas most of us have never seen—a place where people raise their kids, ignore the nudie billboards, and have wine with friends after work—We Are Called to Rise is a story about how life can be simultaneously cruel and beautiful.

The comment period has expired.

|

|