Manuscripts and Archives

More than 70,000 people packed into the Yale Bowl for the inaugural game in the new stadium, against Harvard on November 21, 1914. The Bulldogs lost the game 36–0, prompting one Harvard wag to report that “Yale furnished the Bowl, and Harvard provided the punch.”

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

More than 70,000 people packed into the Yale Bowl for the inaugural game in the new stadium, against Harvard on November 21, 1914. The Bulldogs lost the game 36–0, prompting one Harvard wag to report that “Yale furnished the Bowl, and Harvard provided the punch.”

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives, Collection of Charles A. Ferry

The Bowl's construction took 16 months and is said to have cost about $750,000.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives, Collection of Charles A. Ferry

The Bowl's construction took 16 months and is said to have cost about $750,000.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives, Collection of Charles A. Ferry

The Bowl's construction took 16 months and is said to have cost about $750,000.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives, Collection of Charles A. Ferry

The Bowl's construction took 16 months and is said to have cost about $750,000.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives, Collection of Charles A. Ferry

The Bowl's dramatic shape was celebrated in a 1914 postcard.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives, Collection of Charles A. Ferry

The Bowl's dramatic shape was celebrated in a 1914 postcard.

View full image

Clifford Scofield/Getty Images

Open trolleys carried fans to and from the Bowl until 1947, when trolley service ended in New Haven.

View full image

Clifford Scofield/Getty Images

Open trolleys carried fans to and from the Bowl until 1947, when trolley service ended in New Haven.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives, Collection of Charles A. Ferry

The Yale team took its first practice in the Bowl on November 9, 12 days before opening day.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives, Collection of Charles A. Ferry

The Yale team took its first practice in the Bowl on November 9, 12 days before opening day.

View full image

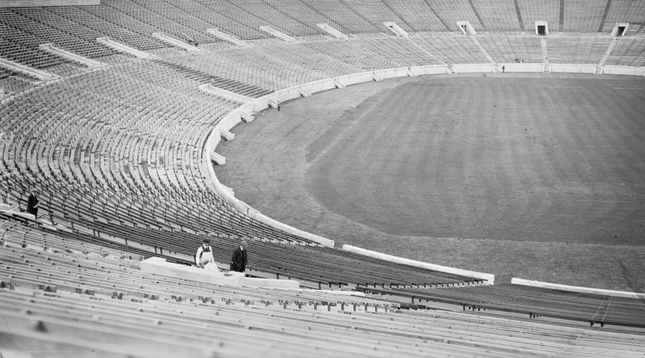

Library of Congress

Opening day at the Bowl (pictured before the fans arrived).

View full image

Library of Congress

Opening day at the Bowl (pictured before the fans arrived).

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

Cornell Daily Sun sports editor Anne Morrissy was the first woman allowed in the Bowl's press box—in 1954.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

Cornell Daily Sun sports editor Anne Morrissy was the first woman allowed in the Bowl's press box—in 1954.

View full image

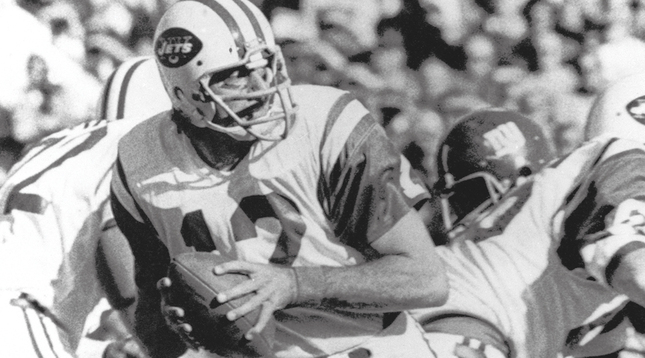

Associated Press

New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath fades back to pass in a 1974 game at the Bowl. The New York Giants used the stadium as their home field for part of the 1973 season and all of 1974.

View full image

Associated Press

New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath fades back to pass in a 1974 game at the Bowl. The New York Giants used the stadium as their home field for part of the 1973 season and all of 1974.

View full image

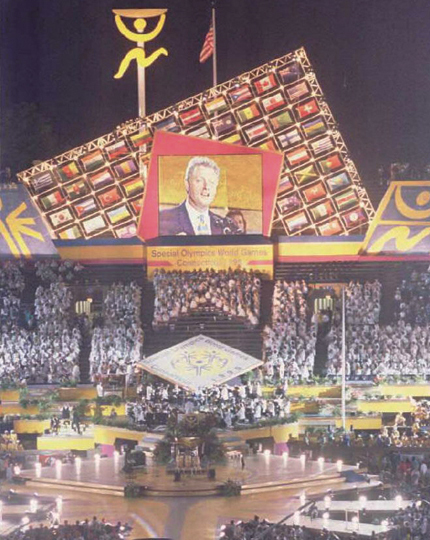

Henry Ray Abrams/AFP/Getty Images

The Bowl was host to the opening ceremonies of the Special Olympics World Games in 1995; President Bill Clinton ’73JD addressed the games on video.

View full image

Henry Ray Abrams/AFP/Getty Images

The Bowl was host to the opening ceremonies of the Special Olympics World Games in 1995; President Bill Clinton ’73JD addressed the games on video.

View full image

Jim Rogash/Getty Images for Sony Ericsson WTA Tour

In 2009, to promote the Connecticut Open tennis tournament, the Bowl's field was turned into the world's largest tennis court by professional players Flavia Pennetta (left) and Caroline Wozniacki.

View full image

Jim Rogash/Getty Images for Sony Ericsson WTA Tour

In 2009, to promote the Connecticut Open tennis tournament, the Bowl's field was turned into the world's largest tennis court by professional players Flavia Pennetta (left) and Caroline Wozniacki.

View full image

James R. Anderson Photography

Among the musical acts to play the Bowl was the Grateful Dead, whose July 31, 1971, concert there was released as a live album in 2008.

View full image

James R. Anderson Photography

Among the musical acts to play the Bowl was the Grateful Dead, whose July 31, 1971, concert there was released as a live album in 2008.

View full image

Bob Macdonnell/Hartford Courant

Eric Johnson ’00, who later played for the San Fransisco 49ers, caught a touchdown pass from Joe Walland ’00 in the final minutes to win the 1999 Harvard game.

View full image

Bob Macdonnell/Hartford Courant

Eric Johnson ’00, who later played for the San Fransisco 49ers, caught a touchdown pass from Joe Walland ’00 in the final minutes to win the 1999 Harvard game.

View full image

Stephen West/Manuscripts and Archives

Yale football coach Carm Cozza (here, at a game against UConn in 1969) led the Bulldogs for 183 games in the Bowl over 32 seasons, more than any other coach.

View full image

Stephen West/Manuscripts and Archives

Yale football coach Carm Cozza (here, at a game against UConn in 1969) led the Bulldogs for 183 games in the Bowl over 32 seasons, more than any other coach.

View full image

Bill O'Brien

Portugal and Italy faced off in front of 38,000 fans at the Bowl in the US Cup soccer tournament in 1976.

View full image

Bill O'Brien

Portugal and Italy faced off in front of 38,000 fans at the Bowl in the US Cup soccer tournament in 1976.

View full image

Next time you sit down to watch the Super Bowl—or any of dozens of other postseason football games—think of Noah Haynes Swayne 2d, Class of 1893. Although Swayne’s life work was in the coal, pig iron, and coke business, he ought to be better known for something he did as a member of the Committee of 21, the Yale alumni group that oversaw the construction of a new football stadium for the Bulldogs in the early 1910s.

According to accounts of the time, it was Swayne who suggested that because of the new edifice’s shape, it should not be called a “stadium” or a “coliseum” but simply the Yale Bowl. It was the first use of the word “bowl” to describe a stadium. Then, when the city of Pasadena borrowed the word for its new Rose Bowl stadium in 1923, their annual postseason football game also took the name, and a bowl became not just a place but also an event.

That is just one of the ways that Yale and the Bowl helped shape American football. Completed in 1914, the Bowl (now a National Historic Landmark) was the first great monument to the game of American football and a symbol of the Bulldogs’ early hegemony in that sport.

Born of the increasing demand for seats at Yale games—its predecessor held 33,000 people, compared with the Bowl’s 61,000—the Bowl was based on classical examples, most notably the Roman amphitheater at Pompeii. Designed by engineer Charles Ferry ’71S and architect Donn Barber ’93S, the concept was simple: dig a hole for the field, then use the dirt to shape the elliptical seating area around it (and build 30 concrete portals to get people in and out). The result is an unforgettable space, a kind of Platonic ideal of a football stadium. “Everyone remembers their first visit to the Yale Bowl,” wrote New York Times sports reporter William Wallace ’45W, “the walk through the pinched, dark tunnel and then: boom. Suddenly the big Bowl is there, spread all the way around in a world of its own.”

Although Yale’s football dominance faded soon after the Bowl was built, the stadium has been the stage for a hundred years of memories, on the field and in the stands. And not just for college football fans: the Bowl has also been home to the NFL’s New York Giants, welcomed the International Special Olympics, and hosted concerts by acts as varied as Bob Hope; Peter, Paul, and Mary; and the Grateful Dead.

This fall, the university is celebrating the Bowl’s centennial with a series of tributes to the stadium’s history at each of the six home football games, including a game with Army, a former rival that the Bulldogs have not played since 1996. (Find out more at yalebowl100.com.) Fans who haven’t been back in a few years will be in for a treat; thanks to renovations over the last decade, the Bowl is looking awfully good for a centenarian.

“The great Yale tradition and the Bowl lend themselves to mysticism. Some players would actually bury their sweatbands and locks of hair under the Bowl turf. The gathering on the field after the games is a magical time. With dusk approaching, the bands playing, and the kids running around the field, it is a very special happening for the Yale players.”—Dave Sheronas ’93, former Yale football captain

“I was an usher for 26 years (1974 to 1999) at Portals 1 and 2. I used to tell people that a big steam shovel used to excavate the ground was trapped inside after the Bowl was built. Being too big to get out, it was buried under the field. You would be amazed at how many people believed that story.”—Stu Cohen, Milford, Connecticut

“The night before the first game [played in the Yale Bowl], I dug a hole under a fence and put leaves in the hole.… The next day I crawled into the hole to get through the fence. I then entered the Bowl through a portal about 7:30 in the morning.… At 11 a.m. the crowd started to file in for the grand opening. An older couple found me curled up like a squirrel, chilled to the bone, and offered me a cup of coffee.”—Al Ostermann (1906–2001), who later operated the Yale Bowl scoreboard for more than 40 years.

“I was at the Bowl in 1983 for the 100th Yale-Harvard game. I took my 18-year-old daughter and it was so crowded, we had to sit on the concrete steps. My daughter asked if the Bowl was always this crowded. I said ‘No, only every 100 years.’”—Tom Hackett ’50, ’53JD

“The designers positioned the Bowl so that the minor axis points to the sun at 3 p.m. on November 15. Thus no football player would ever have to look into the sun when Yale plays its big games against Princeton and Harvard.”—Charles Ferry, Class of 1871S (1852–1924), one of the Bowl’s designers, in a 1916 report to the American Society of Civil Engineers

loading

loading