loading

loading

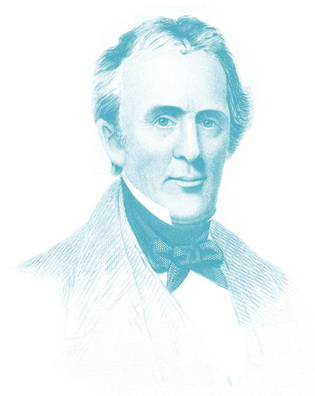

featuresHow science came to YaleBenjamin Silliman, a young lawyer, traveled to Philadelphia in 1802 with a few mineral specimens in a candle box. It was Yale’s first step on the path to becoming a university. Richard Conniff ’73 is the author, most recently, of The Species Seekers. This article was made possible by the Seth E. Frank ’58LLB Literary Fund.  Courtesy Barbara Narendra/Yale Peabody MuseumA typical candle box of the early nineteenth century. In just such a candle box, Silliman carried with him to Philadelphia a few mineral specimens belonging to Yale—the kernel of what would become extensive scientific collections. View full imageOn October 26, 1802, a 23-year-old Yale-educated lawyer boarded a stagecoach in New Haven for the long, dusty, motion sickness–inducing trip to Philadelphia. Under his arm, he carried a wooden candle box full of mineral specimens to be properly identified. They were remnants of a higgledy-piggledy museum of curiosities Yale had maintained for a time but then largely misplaced, not altogether regrettably. The original collection had included a 50-pound set of moose antlers, a nine-foot-long wooden chain carved from a stick by a blind man, and a two-headed calf. It also included miscellaneous unlabeled mineral specimens. The candle box in which Benjamin Silliman, Class of 1796, carried these specimens to Philadelphia would enter Yale legend as the beginning of proper scientific collecting at Yale. More than that, it was the beginning of the collections that would later become the Peabody Museum of Natural History, and the beginning of Yale’s rise from a college to a university. The polymath Thomas Jefferson was in the White House, yet for most Americans then, science was still a foreign enterprise, somewhat nervously regarded. There were signs of growing interest in this strange idea of knowing the world not just by faith but by experiments, expeditions, and observation. But many considered it a threat to their religion and to the idea of a classical education. Timothy Dwight IV ’69, then president of Yale, had seen that it was time for the college to branch out from its primary function as a training ground for Congregational ministers. He wanted to add a faculty position in chemistry and natural history. But Dwight was a pastor and an adamant defender of the Congregational Church in Connecticut, and he was cautious. He said he could find no American who was qualified for the job, and he feared that “a foreigner, with his peculiar habits and prejudices, would not feel and act in unison with us… however able he might be in point of science.” Instead, Dwight had turned in 1801 to Silliman, a recent Yale graduate and family friend, who was known to be devout. So devout, in truth, that he could describe Yale contentedly as “a little temple,” where “prayer and praise seem to be the delight of the greater part of the students.” Silliman admitted to being “startled and almost oppressed” by Dwight’s job offer. He knew nothing about science. It was a spectacularly inauspicious start. Dwight argued his way around Silliman’s concerns. He pointed out that there were already plenty of lawyers, but as a scientist “the field will be all your own.” He also advised Silliman not to pursue a job possibility he had been considering in Georgia, because of the morally repugnant association with slavery. Silliman had become adamantly opposed at Yale to “the sin and shame of slavery,” but his Fairfield County family was neck deep in the Connecticut practice of slaveholding. Dwight cleverly made the Georgia job sound like a kind of falling back. Thus Silliman soon found himself en route to Philadelphia to take a crash course in chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, which had the nation’s first school of medicine. Dwight, it turned out, had chosen wisely. Silliman was certainly devout. But after another year studying and attending lectures in London and Edinburgh, he was also a knowledgeable and enthusiastic teacher of chemistry, and later of mineralogy and geology. He came back to lecture brilliantly at Yale, and these lectures were the beginning of science education in America, that is, of science for its own sake, not merely as an adjunct to medicine. Silliman would become a great name. He was “the Patriarch” of American science, according to Louis Agassiz, the Swiss biologist who would take up the mantle of science education at Harvard in 1847. But Silliman would do so without making any great discoveries, without introducing any bold new concepts or systems, and without ever fitting the stereotype of the scientist as solitary brooding genius. On the contrary. What American science needed then was “an organizer, a promoter, a teacher, a preacher, a public relations man, a communicator and coordinator, and an exemplar of professionalism,” science historian Robert Bruce has written. “Silliman was all of these.” He was a charismatic figure, with a clear and forceful way of speaking and an impressive, even aristocratic physical presence—tall and lean, “erect as a general on parade and with a general’s expression of great power,” as a former student recalled, with a high brow, deep-set eyes, a thin straight nose, and slightly pursed lips—altogether inspiring confidence and even belief in his listeners.  Courtesy Barbara Narendra/Yale Peabody MuseumAn early scientific prize Silliman acquired for Yale: the 36.5-pound meteorite that fell to earth in Weston, Connecticut, in 1807. View full imageSilliman made it his mission to develop science and science education at Yale, and later nationwide. For this, he also possessed the ineffable trait that Bruce describes as “effectiveness in procuring facilities and supplies.” It wasn’t just that he had a keen eye for new material to embellish the Yale collection; he was also adroit at wheedling funds out of the Yale Corporation to pay for these acquisitions. Much of this effort went in support of mineralogy, a topic early Americans found far more tantalizing than we generally do today. For them, it afforded “a pleasant subject for scientific research,” according to an 1816 account, and also tended “to increase individual wealth” and “to improve and multiply arts and manufactures and thus promote the public good.” Mineralogy attracted some colorful personalities. Silliman handed over $1,000, a huge sum then, for one mineral collection, notwithstanding that it had been put together with profits from the most notorious quack medical invention of that era, Elisha Perkins’s “Metallic Tractors.” Silliman’s brother, a lawyer in Newport, arranged the purchase of a mineral collection brought from England by a doctor who then had the misfortune to die in a duel over his “too great familiarity” with the wife of a South Carolina plantation owner. One coveted acquisition eluded Silliman, at least at first. In the darkness before dawn on December 14, 1807, a “globe of fire,” seemingly half the size of the full moon, blazed across the skies of western Connecticut. Darkened rooms went bright as day. Farmers started up from their chores, or sat upright in bed in terror, as if the Judgment Day had come. As locals later described it to Silliman, three “loud and distinct reports,” like cannon shots, burst over the town of Weston, followed by “a continued rumbling, like that of a cannon-ball rolling over a floor.” It was a meteorite, estimated by Silliman to be at least 300 feet in diameter before it broke apart and rained down in pieces. Silliman and a faculty friend, ecclesiastical historian James L. Kingsley ’99, arrived on the scene a few days later to gather eyewitness accounts and obtain a few fragments by purchase (the weeping and teeth-gnashing among local farmers having given way to gleeful profiteering). A detailed report by the two professors, including Silliman’s chemical analysis, concluded that the meteorite had come from outer space. Their account was soon being read aloud before learned societies in Philadelphia, London, and Paris. President Thomas Jefferson was skeptical, supposedly remarking, “I would more easily believe that two Yankee professors would lie than that stones would fall from heaven.” He had reason to mistrust Yale and Connecticut, both then bastions of anti-Jeffersonian Federalism, but the quote was probably apocryphal. The skepticism, on the other hand, was genuine. In a later letter, Jefferson wondered pointedly how the meteorite “got into the clouds from whence it is supposed to have fallen.” Like much of the educated world then, Jefferson was still struggling with the dogma-shattering idea, introduced just a dozen years earlier by the French comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier, that species created by God could become extinct. As a passionate advocate of scientific discovery and president of the nation’s first great scientific organization, the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, Jefferson had authorized funds to excavate the bones of a mastodon—the very species that alerted Cuvier to the possibility of extinction. And yet he also ardently pursued the hope that these mammoth creatures still lived in the unknown American West. Jefferson must have been equally torn now by the idea that the Earth God had made for man could be randomly bombarded from the heavens. (Though if it must be so, why not Connecticut?) These doubts were characteristic of a nation and a time in which ancient cultural and religious beliefs were constantly crashing up against new facts. That is, it was a nation struggling to come to terms with science. In the course of their research, Silliman and Kingsley had spent several hours searching fruitlessly for one unusually large stone that had landed in the town of Trumbull (Silliman’s birthplace, as it happened). When it finally turned up, after they’d gone back to New Haven, it weighed 36.5 pounds—and the lucky farmer who found it thought it was worth $500. An amateur mineral enthusiast, Colonel George Gibbs (the rank was honorific), placed the high bid. He was the heir to a Newport shipping fortune, which he seems to have had no great interest in preserving. Among other acquisitions, he had recently purchased and brought home the extensive mineral collection of a Russian count, and another collection accumulated over 40 years by a great patron of science in France. Even before the meteorite episode, Silliman’s brother in Newport had tipped him off about Gibbs. Silliman and Gibbs soon met, became friends, and spent time geologizing together around New England. In 1810, when he was considering a suitable place to display his mineral “cabinet,” Gibbs made inquiries at institutions from Boston to Washington, without quite finding what he was hoping for. Finally, he stopped in to visit Silliman in New Haven and announced, “I will open it here in Yale College, if you will fit up rooms for its reception.” Yale promptly did so, on the second floor of what is now Connecticut Hall. And thus, among many other treasures, the 36.5-pound Weston meteorite came to Yale.  Manuscripts and ArchivesNorth Sheffield Hall on Prospect Street, finished in 1873, was part of Yale's Sheffield Scientific School. View full image Manuscripts and ArchivesThe first volume of what would become America's leading scientific periodical, edited by Silliman. View full imageGibbs also provided one other critical boost not just to Yale but to American science at large. Late in 1817, he bumped into Silliman by chance one day aboard the steamboat Fulton, on the ten-hour run between New York and New Haven. A mineralogist who had sporadically published a journal for that discipline was in failing health, and Gibbs urged Silliman to take up the challenge of producing a more broadly focused scientific journal. The following year, having sought and received his predecessor’s blessing, Silliman launched the American Journal of Science. It soon became the nation’s premier scientific periodical, often referred to simply as “Silliman’s Journal.” The rapidly growing Yale mineral collection—in truth, still largely the Gibbs collection—meanwhile began to attract important visitors to New Haven. The collection moved, in 1820, to a space upstairs from the new college dining hall, a prominent building in the heart of the campus later known simply as the “Cabinet Building.” For Silliman and Yale, things seemed to be progressing smoothly. But in 1825, Gibbs suddenly announced that he needed to sell. Given his friend’s spending habits, Silliman should have been ready. But he was startled, especially because the price Gibbs named for the mineral collection, $20,000, represented two-thirds of Yale’s annual income. Silliman was soon out raising funds by pamphlet, public meeting, and door-to-door in New Haven and New York. Yale’s new president, Jeremiah Day ’95, also knocked on doors, determined not to lose the collection that, as Silliman put it, had been for “so long our pride and ornament.” In the end, they raised half the asking price, and Gibbs graciously accepted a note for the balance. The collection became the basis around which a community of scholars—scientists, as they were just beginning to be known—began to gather at Yale. Silliman built on the prestige of the collection to help Yale found a science school (later the Sheffield Scientific School); the first college art gallery, largely by arrangement with his wife’s uncle, the artist John Trumbull; and the medical school. All this helped nudge Yale well along the path from a college into a university. Among those who turned their attention to Yale as a result was an amateur mineralogist still at prep school, O. C. Marsh ’60, who carefully noted in his journal a quotation from Silliman on the art of acquisition: “Never part with a good mineral until you have a better.” Marsh would later study under Silliman and in time help found the Peabody Museum to house the mineral collection properly. He would also use the museum to make Yale the great center of paleontological discovery in the nineteenth century, going into the American West to bring back the sort of monstrous creatures—Brontosaurus, Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops—that would have delighted Jefferson, except that they were thoroughly extinct. Another Silliman student, Daniel Coit Gilman ’52, would become the college librarian and an important figure in the rise of Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School. He would move on to become the first president of Johns Hopkins University and later of the Carnegie Institution, both with a focus on fostering scientific research. Still another student of Silliman’s, Amos Eaton, would help found what is now the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and pioneer the practice of applying the scientific method “to the common purposes of life.” Silliman accomplished so much in part by nepotism. By the time he retired in 1853, he had established a family dynasty in science. Daniel Coit Gilman was distant kin: his brother had married a Silliman daughter. George J. Brush ’52PhB, a mineralogist and later director of the Sheffield Scientific School, had married Harriet Silliman Trumbull, a Silliman cousin. The faculty also included Silliman’s son Benjamin Jr. ’37, a chemist who would play a key role in launching the Age of Petroleum, and Silliman’s former student and son-in-law James Dwight Dana ’33, who was both a zoologist and a celebrated geologist. Dana’s son Edward S. Dana ’70, ’76PhD, would also eventually join the faculty. What mattered, beyond the nepotism, was that Silliman had made it seem perfectly reasonable for Yale, the former Congregational seminary, to employ eight faculty members in science versus just five for theology.  Manuscripts and ArchivesLithograph portrait of Daniel Coit Gilman ’52, taken for his graduation. Gilman, a student of Silliman's, would go on to become the first president of John Hopkins University. View full imageThe line dividing science and theology was, however, still practically nonexistent, and in this somewhat delicate context, James Dwight Dana was undoubtedly the most important of Silliman’s disciples. He was both a deeply religious man and the greatest American geologist of the nineteenth century, and much as Silliman had done for Timothy Dwight, he made it possible to expand the role of science without seeming overly threatening to religion or the humanities. Dana also explicitly took up Silliman’s mission of using the sciences to build Yale into a university. In 1856, Dana gave a speech to Yale alumni lamenting those “who still look with distrustful eyes on science.” They seem, he said, “to see a monster swelling up before them which they cannot define, and hope may yet fade away as a dissolving mist.” That specter was twofold: the shadow cast by geology on the Genesis account of the Earth’s history, and the idea of evolution, which was already in the air. (Among other developments, a former student of Silliman’s named Thomas Staughton Savage ’25, ’33MD, a missionary, had recently brought home from Africa the bones of an unknown primate with a disturbing resemblance to humans—the gorilla.) But Dana was deeply committed to a biblical view of creation, and he assured his listeners of the evidence provided by geology “that God’s hand, omnipotent and bearing a profusion of bounties, has again and again been outstretched over the earth; that no senseless development principle evolved the beasts of the field out of monads”—that is, unicellular organisms—“and men out of monkeys, but that all can alike claim parentage in the Infinite Author.” (Silliman shared this belief. In one of his last lectures he had declared, “Young men, those people may think as they please but for my part I shall never believe or teach that I am descended from a tadpole!”)  Manuscripts and ArchivesAn undated engraving of Silliman. His statue stands today in front of Sterling Chemistry Library. View full imageHaving dismissed the evolutionary bugaboo, Dana went on to argue for the expansion of scientific study on the Yale campus, with new laboratories, lecture halls, and above all a museum, “a spacious one.” This museum, Dana said, “should lecture to the eye, and thoroughly in all the sections represented, so that no one could walk through the halls without profit. It should be a place where the public passing in and out, should gather something of the spirit, and much of the knowledge, of the institution.” Then rising to his conclusion, he called on the alumni to help build “the first university in the leading nation of the globe.… Why not have here, in this land of genial influences, beneath these noble elms… why not have here, THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY,—where nature’s laws shall be taught in all their fullness, and intellectual culture reach its highest limit!” By coincidence—or perhaps Dana would say “miraculously”—the means of making the first part of this vision a reality arrived in New Haven just days after Dana’s speech. On August 3, 1856, the aspiring freshman O. C. Marsh took the exam for admission to Yale. By good fortune for all, he aced it. Ten years later, with money from his uncle George Peabody, a leading merchant banker, Marsh and Dana together would found the Peabody Museum. The second part of the vision, creation of a great American university, would take a little longer. Though some people in the humanities continued to regard it with suspicion, the Sheffield Scientific School was able to expand its faculty and become a greater presence on campus. The New Haven railroad magnate Joseph E. Sheffield had not attended Yale, but no doubt in part because his son-in-law John Addison Porter ’42 taught chemistry there, he provided continuing support for the school that was now named for him. Yale was also one of the first schools to take advantage of the Morrill Act of 1862, a national land-grant program promoting technical and scientific education. Yale would not officially call itself a university until 1887, after another Timothy Dwight, Class of 1849 and the grandson of the Timothy Dwight who had hired Silliman, became its president. Even as late as 1885, the Nation could still describe Yale as “an institution practically governed by a few clergymen of a single denomination in a single state.” But the change was well under way. By the early 1860s, with the Peabody and Sheffield gifts adding to the Morrill Act money, Yale scientists knew it. Mineralogist George J. Brush was exultant: “You can form no idea how every one seems [to] have waked up to the fact that Yale is to be a great university.” Dana agreed: “The time of her renaissance has come!!”

|

|