loading

loading

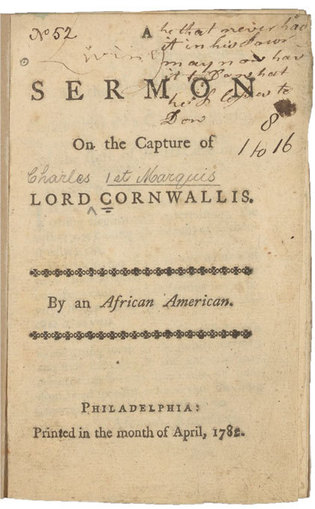

Arts & CultureThe origin of “African American”The term’s earliest known appearance in print is in an eighteenth-century sermon. Yale law librarian Fred R. Shapiro is working on the second edition of the Yale Book of Quotations.  Houghton Library, Harvard UniversitySend your quotation leads and questions to “You Can Quote Them,” Yale Alumni Magazine, PO Box 1905, New Haven, CT 06509-1905, or [email protected]. View full imageMost of us became familiar with the ethnonym African American in the 1980s, when Jesse Jackson began popularizing it as an alternative to black. (An ethnonym is a name by which an ethnic or racial group is known.) But the term is much older than that: recently, I found an example dating back to the earliest days of the American republic. The Oxford English Dictionary traced its documented occurrences of “African American” back as far as 1835. (The related term “Afro-American,” which enjoyed a brief popularity in the 1960s, has an 1831 citation in the OED.) But last April, I did a routine search for the phrase in America’s Historical Newspapers, the Readex company’s very powerful database of early US papers, and was surprised to be led to a 1782 sermon published in Philadelphia. The sermon, whose only known surviving copy is at Harvard’s Houghton Library, was titled “A Sermon on the Capture of Lord Cornwallis.” The title page of the pamphlet includes the byline “By an African American.” The sermon gives few clues about the identity of the preacher, but I concluded that it was written by someone who was black, had some ties to South Carolina, and by his own admission did not have “the benefit of a liberal education.” Beyond that I had no clue as to his background or what kind of a person he was. So I sought some expert advice. Richard Newman, a scholar of African American history and now director of the Library Company of Philadelphia, says he is not sure that the author was a person of color, despite the byline. “The tone and style of the pamphlet diverge from some key aspects of black writing at the time,” Newman says. “Where many African Americans emphasized the story of Exodus—which highlighted Biblical prophecy that unrepentant masters would be punished by a righteous God—this pamphlet focuses on the tale of Samuel. The theme of this Old Testament story would surely have resonated with both slaves and free blacks: The Mighty Will Fall. Nevertheless, the Biblical exegesis that follows focuses more on keeping the faith in the Lord rather than smiting slaveholders.” On the other hand, Edward Rugemer, associate professor of African American studies and history at Yale, believes the writer was black, and finds significance in the fact that the pamphlet was published in Philadelphia. “With the Revolution, when a significant number of Upper South slaveholders began to manumit their slaves, freed people from Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware were attracted to Philadelphia,” says Rugemer. In the sermon, the author addresses “my own complexion, Ye who are my brethren, my kinsmen according to the flesh; ye descendants of Africa.” Rugemer notes that “of those blacks who took an active part in the war, more served in the British Army than in the Patriot forces.” The author asks rhetorically of those black Tories, “Have ye not been disappointed? Have ye reaped what you labored for?” “I’ve been under the impression that most of this black loyalist group left with the British,” says Rugemer. “This sermon suggests that many in fact stayed and the writer is arguing that they move on and embrace the American experiment.” On this point Newman agrees. “If it was written by an African American,” he says, “the pamphlet may indeed have been strategically aimed at integrating blacks into the new social and political order. This notion fits nicely with the author’s byline: ‘an African American.’ The idea that blacks might be part of American society was in the air by the 1760s.”

|

|

2 comments

-

Paul Petry, '90, 4:55pm January 17 2016 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Mark Branch, 11:10am February 04 2016 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.The link to the sermon on Houghton Library’s website does not work.

Sorry about that. It's fixed now!