loading

loading

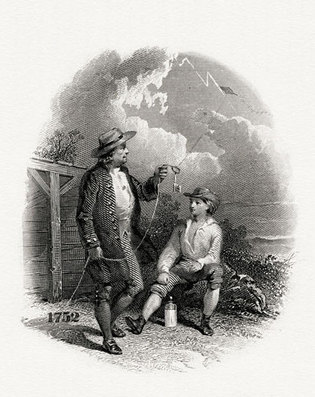

What’s in a name? Wikimedia CommonsBenjamin Franklin’s famous experiment with electricity is depicted in an engraving that was used on the US ten-dollar national bank note from the 1860s to the 1890s. View full imageBenjamin FranklinWhen Benjamin Franklin was a 16-year-old printer indentured to his brother James, editor of Boston’s New England Courant, he satirized a great Yale scandal: when President Timothy Cutler and one of the tutors converted to Anglicanism. Thirty-one years later, he received an honorary master’s degree from the college for his contributions to science; he soon became a frequent correspondent of Yale president Ezra Stiles, eventually donating books to Yale and a thermometer for Stiles’s scientific inquiries. Fast-forward another 37 years: in one of his last letters, in 1790, he carefully turned down Stiles’s request for a portrait to hang next to that of Elihu Yale. But he offered to sit for one, calling the college “the first learned society that took notice of me, and adorned me with its honors.” Franklin was a servant and apprentice, with hardly any formal education, who became an artisan, then a master printer and entrepreneur. He created the business model that printers and newspaper editors sought to follow: serve the public by suggesting and organizing civil improvements like libraries and fire companies and a hospital, encourage free inquiry and political discussion, and make your money on the advertisements. By the time he was 42 he could retire and devote himself to gentlemanly pursuits—science, inventing, more-ambitious writing projects, politics, and public service. His international fame came with his experiments demonstrating properties of electricity. In the coming years he became also the most widely known American in the world personally, as he represented several of the colonies in London between 1757 to 1775, and negotiated for the United States in Paris during and after the revolutionary war. Franklin’s gift for words, and for getting along, served him extremely well in Pennsylvania and in the British Empire. He organized the North American postal system, attempted to fashion a new plan of union for defense during the Seven Years’ War, and tried to explain the colonists’ protests against new taxes. Fired from his position as Postmaster General for his opposition to crown policies, he returned to Philadelphia a strong supporter of resistance in the Continental Congress and served on the committee that edited Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence. His relationship to slavery and antislavery was complex. Franklin held several slaves during his working years, and his newspapers ran ads for other slaves’ sale and recapture. Yet he printed some early abolitionist tracts (without putting his name on them as printer), even though he did not divest himself until the last bondsman, George, died in 1781. Franklin joined the first antislavery society in Philadelphia, but he did nothing publicly at first, declining to bring an antislavery petition to the Constitutional Convention of 1787. During his last two years of life, after his political career ended, he took public action—serving as honorary president of the society and in February 1790 signing an abolitionist petition that asked Congress to “secur[e] the blessings of liberty to the ‘People of the United States’ . . . without distinction of color.” It was Franklin who invented and publicized the most lasting notions of the American. His cultural diplomacy helped Americans define themselves as virtuous, hardworking, simple folk—much as Franklin projected himself in France, wearing his homemade bifocals, a beaver hat, his own hair, and a plain brown coat—who just might deserve backing as a kind of hybrid of European virtues in the rough new world. Franklin, celebrated as the most cosmopolitan and the most American of the revolutionaries, is probably the most universally appreciated of the American “founders.” David Waldstreicher ’94PhD is Distinguished Professor of History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

The comment period has expired.

|

|