loading

loading

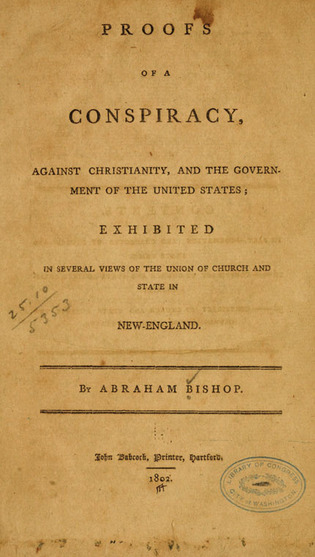

Old YaleA firebrand from the Class of 1778Abraham Bishop was a noisy Republican in a Federalist state—and an early advocate for women and African Americans. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  Library of CongressAbraham Bishop, Class of 1778, wrote fiery political pamphlets that went against the grain in Federalist New England. View full imageThe Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of the American Enlightenment calls Abraham Bishop, of the Yale College Class of 1778, a “key subject in early American history.” It explains: “In his challenge to clerical and political power, his championing of natural rights regardless of skin color, and his protest against traditional gender roles, Bishop embodied the prototypical ideals of the American Enlightenment.” Yet Bishop was excluded from Anson Phelps Stokes’s classic Memorials of Eminent Yale Men, and Franklin B. Dexter, Secretary of Yale from 1869 to 1899, expressed doubt that he might ever become “a really historic character.” Indeed, Bishop has now fallen into obscurity—perhaps because he was a Republican in an overwhelmingly Federalist state. Abraham Bishop (1763–1844) was the son of Samuel Bishop, a distinguished New Haven judge, public officer, and mayor. The family was Federalist, as were almost all of Abraham’s Yale classmates, and at first he seemed destined to join them. After graduating from Yale at the young age of 15, he was admitted to the bar in 1785. Then, early in 1787, he began a two-year trip through Europe. When he returned to New Haven in 1789, he had been enriched by visits to great libraries and English debating sessions, and he was, noted Yale president Ezra Stiles, Class of 1746, in his diary, “full of Improvement and Vanity.” Bishop took to public speaking, often criticizing the political power of the Christian religion and the new Constitution, and drew large audiences. Newspapers followed him, and he published his speeches widely. For a time he turned his attention to reforming the local school system—in which, he said, “the youth of both Sexes shall be instructed.” In 1789, he became the director of the American Academy, and in 1790 the head of the Hopkins School. Seeking a wider audience, he moved to Boston in 1791. There he contributed to The Argus, writing on a range of topics. Two significant series of essays drew national and lasting attention. In “Female Education,” he wrote: “Even now, in some parts of United America, as well as among several other nations, who call themselves civil[ized]—Women are considered as little better than slaves to unfeeling parents, and to idle lordly husbands.” He believed that with female education, “our daughters will shine as bright constellations, in the sphere where nature has placed them.” In the second series of essays, he supported the slave revolt in Haiti, considering it part of the international spirit of revolution. “Let us be consistent Americans,” he wrote. “The blacks are entitled to freedom, for we did not say all white men are free, but all men are free.” His critics dubbed him the “Connecticut Stranger” and “Jack Ranter.” Bishop left Boston, lived in New Hampshire for a time, and returned to New Haven in 1792 with a wife. His personal and professional life deteriorated in the 1790s; he divorced in 1797, and his court clerkships (obtained with his father’s political influence) were threatened by Federalist purges of Republicans from appointed offices. But he continued to write. Late in 1797 he published “Georgia Speculation Unveiled,” denouncing the Yazoo Land Company fraud in Georgia, in which he and many fellow New Englanders had lost money. “Men who never added an iota to the wealth or morals of the world,” he wrote, were “plotting the ruin of born and unborn millions. . . . These are the robbers of modern days.” In the 1800 presidential election year, Connecticut Republicans had hopes of victory, and Bishop found a new career as a party politician. In August, candidate Aaron Burr came to New Haven to confer with party leaders. This event may have been what inspired Bishop’s plan to wax political when invited to deliver a Phi Beta Kappa address at Yale. The day before the speech, Phi Beta Kappa officers learned that his (anti-Federalist, pro-Republican) address was titled “An Oration on the Extent and Power of Political Delusion.” They canceled his appearance. Bishop at once published a notice that his oration would be delivered in a nearby hall and would be on sale immediately. (His classmate Noah Webster wrote an anonymous retort, “A Rod for the Fool’s Back.”) Later, Bishop would claim that Phi Beta Kappa should have known he wouldn’t pick an academic subject: “The society knew that I could not write about broken glass, dried insects, petrifactions, or any such literary themes.” In the event, the Federalists kept control in Connecticut, but Thomas Jefferson won the presidency. He rewarded Bishop’s support by appointing his father to the lucrative post of Collector of the Port of New Haven; upon Samuel’s death in 1803, Abraham succeeded him. Bishop spent the second half of his life as a wealthy New Haven civic leader, real estate owner, gentleman farmer, and donor to the Yale library. He owned hundreds of acres in New Haven, and he developed Wooster Square and the current Orange Street and Lower State Street historic districts. Several streets—Bishop, Clark, Foster, and Nicoll—are named for him and his married daughters. Bishop died in 1844. More than a hundred years later, one organization sought to make amends for a slight. It seems that Bishop’s name had been crossed out in the rolls of Phi Beta Kappa at Yale by a disgruntled record-keeper, giving rise to the story that he had been expelled from the group. In 1956, the New York Herald Tribune reported that “the Yale Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa . . . acted today to restore the name of Abraham Bishop, a supporter of Thomas Jefferson, which was removed from its rolls in 1800 for political reasons.”

|

|

1 comment

-

Thom Peters, 1:23pm November 28 2016 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.In his book entitled, "The Radicalism of the American Revolution," Gordon Wood described Bishop as: "...one of the greatest popular demagogues in American history. Whatever private demons he had were unleashed on the bewildered and frightened Federalist gentry of Connecticut." (page 275). In trying to describe him to my students, I have difficulty naming a modern contemporary. He was an economic populist, but also a civil rights gadfly. Maybe Bernie Sanders, but somehow more obnoxious to his foes.