loading

loading

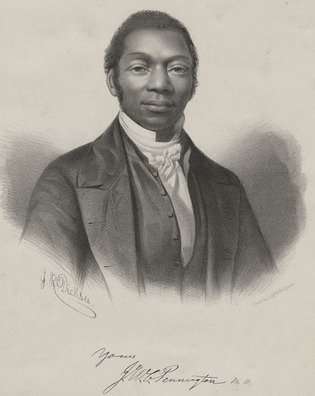

From the EditorYale’s first black studentHe wasn’t allowed to speak in the classroom. Now there’s a classroom named for him.  National Portrait GalleryView full imageIn this mid-1800s portrait, James W. C. Pennington smiles with a relaxed dignity that makes one want to strike up a conversation with him. It would be a profound one. Pennington, the first African American to attend Yale classes, was a prominent pastor, writer, and abolitionist. He was also a former slave. In his memoir, Fugitive Blacksmith (1849), Pennington wrote that as a youth he had seen his father viciously whipped and his mother threatened; had been flogged with a hickory whip because he had found it on the ground “and boy-like, was using it for a horse”; had seen children sent to the deep South in chain gangs. His family lived in Maryland, one of the states said to practice “the mildest form of slavery”—a concept he debunked. The most humane master, he wrote, would turn brutal if his property were threatened: “Talk not then about kind and Christian masters. They are not masters of the system. The system is master of them.” The reality of the chattel system could be seen in a slaveholder’s family record, where a slave “finds his name on a catalogue with the horses, cows, hogs, and dogs.” Pennington (born James Pembroke) escaped in 1827, when he was 19, and made his way to Pennsylvania. There he hid with a Quaker couple for six months, and there he also discovered reading and writing. He moved on to Long Island, where he was able to support himself—he had been trained as a blacksmith—and continue his education. After a crisis of faith, brought on by the question “What can I do for that vast body of suffering brotherhood I have left behind?” he decided to devote himself to fighting slavery and becoming a minister. Pennington achieved a position as a teacher, and then determined to study at the Yale Divinity School. Connecticut prohibited educational institutions from teaching African Americans, lest “colored emigrants . . . rush in from every quarter.” But Pennington worked out a compromise: he could sit in lectures, but could not enroll, use the library, or speak in class. Despite the humiliating restrictions, he started in the fall of 1834 and continued for at least two years. In 1838, Pennington officiated at the marriage of Frederick Douglass and Anna Murray. He became a leading abolitionist and headed churches in several states. In 1841, he published the first African American history textbook. In 1849, Heidelberg University gave him an honorary doctorate. He died in 1870. In October, the Yale Divinity School named one of its largest classrooms after him. “I think it is fitting that a student who could not speak while in class will now have his name spoken every day,” YDS dean Gregory Sterling told YaleNews. “Honoring him now is an attempt to right a wrong.” Or in Pennington’s words: “I beg our Anglo-Saxon brethren to accustom themselves to think that we need something more than mere kindness. We ask for justice, truth, and honor as other men do.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|