loading

loading

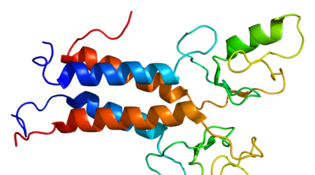

FindingsTackling a hard-to-treat breast cancerScience finds another piece of the cancer puzzle.  Wikimedia CommonsDiagram of the BRCA1 protein structure. View full imageSome of the hardest breast cancers to treat are the triple-negative tumors. They’re called “triple negative” because they lack three common cell receptors—and without those receptors, a tumor cell offers few places for targeted hormone or antibody treatments to latch on and attack. Even standard chemotherapy often fails. Tumors of this kind, known as TNBC tumors, occur most often in young women and women of African descent, whatever their age. There’s a bright spot: for about one in three TNBC patients, chemo works beautifully, leading to a cure. What sets that subgroup apart? A team of Yale researchers, working with colleagues at institutions in Texas and Hungary, has figured it out. The answer doesn’t lie in a single genetic difference. Instead, it involves two cell signaling pathways that can be affected by any number of mutations or switched-off genes. Mess up those pathways, and the resulting tumor is likelier to respond to chemo. One gene frequently involved is a DNA repair gene called BRCA1. It’s already known to cause cancer in people born with a mutated version. But it can also be altered later in life. In the study, TNBC patients who had “BRCA-deficient” tumors—in which the BRCA gene wasn’t working—did well with chemotherapy. The immune system seems to be part of the reason why. “We think the signal from BRCA deficiency helps recruit immune cells around the tumor, which makes chemo more effective,” says lead author Christos Hatzis, assistant professor of medicine.

The comment period has expired.

|

|