loading

loading

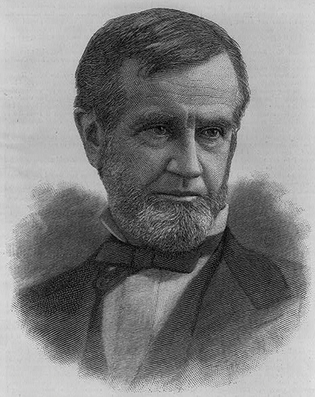

Old YaleThe man who made time workableA Yale-educated schoolteacher invented the US time zone system. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  Library of CongressCharles F. Dowd (1825–1904), Class of 1853, made the lives of travelers incomparably easier when he came up with a new model for keeping time. View full imageAccording to the Wall Street Daily News of November 16, 1904, “It is related that Chauncey M. Depew [’56], once being asked whom he considered the most famous member of the class of ’53, replied that, judged by the importance of his achievements, Dr. Charles Ferdinand Dowd was not only the most famous member of his class, but entitled to the distinction of being the most famous Yale graduate.” Depew, a US senator, had been the president of a railroad. Though most of them did not acknowledge it as graciously as Depew did, every railroad executive had reason to thank Dowd. He invented the system that literally kept their trains running on time. Dowd was born in Madison, Connecticut, in 1825. Financial hardship before and during his Yale years disrupted his education; he worked as a shoemaker for his father, and later he taught school. Officially in the Class of 1853, Dowd earned both BA and MA degrees in 1856, at the age of 31. He and his wife—Harriet Miriam North, a graduate of Mount Holyoke Seminary—ran the North Granville (New York) Ladies Seminary from 1860 to 1867. In 1868 they became coprincipals of the Temple Grove Seminary in Saratoga, New York, where they stayed for 35 years. Dowd’s great project was the collision of train travel and the time system. In those days, local time was calibrated to the sun’s noon mark. This produced a variety of time standards, which was a problem for train travel. Travelers from Portland, Maine, to Buffalo, New York, would traverse four different time zones. Moreover, each railroad system had its own time system, based on the local time of one of its cities. Dowd saw that, given the rapid development of rail lines and steamship routes—as well as telegraph and mail service—the confusion would soon be overwhelming. At first he considered a uniform national time, like England’s system. But when he studied solar times at US railroad stations—“a task that required looking up and converting the longitude of 8,000 places,” writes historian Ian R. Bartky—he found differences of up to four hours. That would make a uniform railroad time system unwieldy. Then, Dowd came up with the concept of four “hour sections,” each spanning 15 degrees of longitude. Inside each section, the time would be uniform; crossing from one section to another would lose or gain one hour. “The concept of hour-difference zones was his alone,” writes Bartky. After meeting with railroad officials, in 1870 Dowd issued the pamphlet “A System of National Time for Railroads.” His plan was endorsed by several West Point and Yale professors. But there were hurdles. Crossing the one-hour boundaries would be a complex problem for the railroads. Further, the nearly 500 railroad companies were focused on competitive rates and speed, not cooperative time agreements. And cities that took pride in their local times would not want to compromise. Albany, New York, and Montreal differed from each other by only a minute, yet all stuck to their individual times. Dowd worked for the adoption of his plan by continually meeting, talking, and writing on the subject. The railroads were not receptive. But eventually, a plan modeled on Dowd’s was adopted in 1883. Over the years Dowd had studied theology and was ordained, but he had no time for a pastorate. In 1888 he received a Doctor of Philosophy degree from New York University, and in the same year he was made a Fellow of the Society of Science, Letters, and Arts of London. At his 50th Yale reunion, he was called “Father Time” and recognized as Yale’s greatest graduate for the way his system of standard time had affected the entire world. Charles Dowd’s death was tragic, and ironic: in November 1904, at a street crossing in Saratoga Springs, he was killed instantly by a railway train. At the time, and for some years, he had been perfecting an international standard time system with a 24-hour day.

The comment period has expired.

|

|