loading

loading

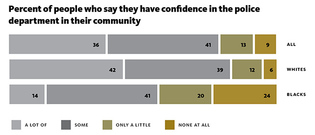

featuresEveryday justiceLaw School professor Tracey Meares is helping police to build trust with civilians. Cathy Shufro, a fellow of the International Reporting Project, teaches writing at Yale.  View full imageProfessor Tracey Meares has sandwiched this trip to Chicago between two teaching days at the Yale Law School, timing it for when her kids are out of the house. On this cool Thursday morning in May 2017, she’s back in her favorite city, where she lived for almost 20 years. She’s come to Chicago State University to help train investigators for the city’s new Civilian Office of Police Accountability. At Yale, she teaches students in their 20s, in a wood-paneled room hung with portraits in oil, but here in this windowless, fluorescent-lit room, her students are three dozen former prosecutors, defense attorneys, and ex-cops. They will soon begin investigating complaints against Chicago’s often reviled police. Meares, 50, paces as she speaks, pausing now and then to scrawl on a whiteboard. She begins by telling the group that she rejects the conventional idea that, above all, police should be crime fighters. Police should be guardians, she says, not warriors who alienate the people they have sworn to protect. Moreover, “Aggressive policing is not very powerful at all,” says Meares. “It is expensive, and it frequently backfires.” Meares’s visit today is part of a larger undertaking. For 20 years, she has been combining legal scholarship with social science research to study policing. She represents a growing cadre of police chiefs, mayors, and criminal justice scholars who advocate “procedural justice,” an approach to policing that fosters mutual respect between police and civilians. Meares didn’t originate procedural justice, but, along with Tom R. Tyler, Yale’s Macklin Fleming Professor of Law, she has verified, explained, and championed its principles nationwide. Meares argues that our democratic system will work better if people can view representatives of the state, including police, as allies. “When people trust the institutions they have a right to rely on, it’s more democratic, it’s more fair. It’s really a fundamental component of citizenship.” She has shared these ideas with the police themselves, both by visiting police departments and by teaching other trainers. “Tracey Meares has been on the leading edge of translating the principles of justice and legitimacy,” says former New Orleans and Nashville police chief Ronal Serpas. She’s also made her case in high places. When President Barack Obama created his Task Force on 21st Century Policing in 2014, he named Meares as one of 11 members. Meares often points out that even though crime in the United States has fallen dramatically during the past three decades, only 36 percent of Americans have “a lot of confidence” in their local police. Among African Americans, the rate is 14 percent. Twenty-first-century police are in trouble.

If Tracey Meares hadn’t been “a lazy student” during college, she probably wouldn’t be a lawyer today. She grew up in Illinois, first in the college town of Champaign (“in the heart of corn country”) and then in Springfield. After high school, she returned to Champaign to study structural engineering at the University of Illinois. “I was a kid who was able to get really good grades by doing very little,” says Meares. As a college junior, she thought medical school might be fun. The admissions test looked easy. But her adviser warned that he wouldn’t sign her application unless she took biology senior year. “That seemed like more work than I wanted to do at the time,” she recalls. “I said, ‘OK, I guess I’ll be going to law school.’” She’d been in second grade when she first faced racism. She and other girls in her class, all of the others white, had walked from school to a classmate’s house for their first-ever Brownie meeting. The classmate’s mother told Tracey the troop was full; Tracey should phone home and wait for her mother on the front steps. “I didn’t understand what was going on at all,” Meares says. “Why couldn’t I go to the Brownie meeting with all of my friends?” Her mother, a high school history teacher, “was furious.” When another mother started a Brownie troop, all the girls transferred except the one whose mother had left Meares on the steps. Meares’s grandmother had been active in the civil rights struggle. Velma Carey helped organize a lawsuit to desegregate the Springfield public schools, and she was a plaintiff in a suit to reform a discriminatory voting system in the city. She was the first African American sales clerk at Myers Brothers department store. This was a big deal, says Meares, because her grandmother worked in cosmetics: “She was touching the skin of white women.” Meares doesn’t see family history as the only reason she entered law school. “I’m a faithful person,” she says. “God had a plan for me.” She graduated cum laude from law school in 1991. She clerked for federal appeals court judge Harlington Wood Jr. for a year, then worked for the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department. She returned to the University of Chicago Law School to teach in 1993, and in 1999 she became the first African American woman in its 97-year history to earn tenure. When she joined Yale Law School as the Walton Hale Hamilton Professor of Law in 2007, she was the first African American woman with tenure in its 173 years. Once at Yale, Meares joined with Tyler to establish The Justice Collaboratory to “rethink and reform” the criminal justice system. The Collaboratory comprises 21 researchers in multiple disciplines who study people’s day-to-day experiences of the system. They have examined, for example, how prosecutors manage plea bargains; how corrections officers interact with inmates; and how police behave when assigned to schools. Their aim is to develop a fairer criminal justice system by connecting theory with on-the-street research. Meares’s interest in social science research was sparked by a conversation with Harvard professor Randall Kennedy in the mid-1990s. Meares and Kennedy were discussing a new law requiring sentences for crack cocaine possession to be 100 times longer than sentences for powdered cocaine. The longer prison terms mostly affected black people, but Kennedy noted that African American politicians supported them. He also claimed that the larger African American community did, too. Meares remembers what she said next: “‘How do you know? Did you ask anybody other than your grandmother?’ And he looks at me and he’s, ‘No, I don’t know; why don’t you figure it out?’” She took his advice and studied statistics and regression analysis at the University of Michigan. (She couldn’t prove or disprove Kennedy’s contention. “It’s complicated,” she says.) Many legal scholars invoke social science research to support their arguments, but Meares says she’s different: “I don’t just cite social science; I do it.”  Chart: Mark Zurolo ’01MFAThe statistics are from a survey of US adults conducted in 2016 by the Pew Research Center. (Whites and blacks include only non-Hispanics; the “no answer” category is not shown.) View full imageIn a roundabout way, it was the 2014 police shooting of Laquan McDonald that brought Meares to Chicago to train the new Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA). On the night McDonald died, a caller had alerted Chicago police that someone was breaking into vehicles in a South Side trucking yard. Police cars began following McDonald. A police dashboard camera recorded what happened next: an African American teenager walks away, his back to the camera, seemingly ignoring the police. He holds a small knife in his right hand. As he passes patrol cars to his left, he suddenly spins and falls. His body jerks again and again as bullets hit him, 16 in all. City officials called the shooting of the 17-year-old a “tipping point.” McDonald’s death caused widespread protests, and outrage flared again 13 months later when a court forced police to release the video. On that day, Officer Jason Van Dyke was charged with murder. And so the COPA trainees will serve a city where many citizens fear and distrust the police. The city’s own 2016 study acknowledged the “deaths of numerous men and women of color whose lives came to an end solely because of an encounter with CPD”—the Chicago Police Department. It concluded, “The community’s lack of trust in CPD is justified.” Meares is all about trust. Collaborating with expert police trainers, she and Tyler have written an eight-hour procedural justice curriculum that was adopted by the Obama Department of Justice and has been taught to cops in cities from Minneapolis to Pittsburgh to Mexico City. She’s teaching a shorter version in Chicago. The 37 trainees listen intently as Meares explains that civilians are far more likely to cooperate with police and others with power if they see them as legitimate—that is, entitled to exercise authority. To maintain legitimacy, police themselves must act lawfully. But that’s not all. Research shows that people care less about police lawfulness than about how the officer treats them. They care more about how they’re treated than about the outcome of a police encounter, such as whether they get a ticket. Meares and Tyler have studied years’ worth of social science research, and they’ve concluded that civilians who interact with police and other authorities want four things. These four elements constitute procedural justice. First, people want “voice”—the chance to tell their side of the story. Second, they want fair decision-making, in which decisions are based on facts and are consistent and neutral, and they want police to explain how they reached those decisions. Third, people want police to treat them politely, with dignity, and with respect for their legal rights. Finally, they want benevolence, to be treated as if they count. They want to feel confident that police are motivated by good intentions. “There is a long research tradition with literally hundreds of studies showing that these matter to people” and lead them to view police as legitimate, Meares says. She’s made her own contributions to this research. For instance, along with Tyler and Jacob Gardener ’11JD, she showed real-life videos of police encounters with civilians to 1,361 study participants from 15 cities. The results confirmed that people cared more about whether the police seemed fair than whether they appeared to follow the law. Meares has also analyzed police practices that alienate civilians. In her 2014 article “The Law and Social Science of Stop and Frisk,” she examined numerous studies of the massive escalation of police stops that many departments initiated roughly 20 years ago. A Supreme Court decision had given police license to stop and frisk anyone if they had “a reasonable suspicion” that the person was armed and was breaking the law. In New York City, with its population of more than 8 million, police stopped 4.4 million people between January 2004 and June 2012. Most were people of color. In 2006 alone, police stopped 77 out of every 100 black male New Yorkers ages 15 to 19. Yet for every 1,000 people frisked, police discovered only 1.5 serious crimes (those resulting in prison terms of at least a year). When a federal judge halted New York’s stop-and-frisk campaign in 2013, she likened it to “burning down a house to rid it of mice.” In another article, Meares and coauthor Benjamin Justice write that stop-and-frisk, and other police practices, send “certain citizens clear signals that they are members of a special, dangerous, and undesirable class, even when police claim only to be doing their jobs—fighting crime on behalf of impoverished and disproportionately minority communities.” Meares has had her own experience with the difference procedural justice makes. She tells the COPA group about an encounter with a cop a decade ago, when she was still teaching in Chicago. She was driving her three children in the family’s Honda Odyssey when a police officer pulled her over. At that moment, Meares said, “I totally knew I had rolled through the stop sign.” Moments before, her one-year-old had begun to scream, and Meares had managed to pass him a bag of Goldfish crackers. The baby had “very inconveniently” calmed down by the time the officer arrived at the driver’s-side window. Meares says she felt compelled to explain why she’d been distracted. “I really needed to tell my side of the story,” she says. Whether she got a ticket or not, she didn’t want the cop to view her as a heedless driver. (She didn’t get a ticket.) When citizens feel confident that police will treat them justly, Meares says, the benefits pervade community life: “They are more likely to spend money in their communities, to vote, to be civically engaged. This is very, very powerful.”

Tracey Meares’s schedule is so complicated that her administrative assistant, Patty Milardo, needs the skills of an air traffic controller. This fall Meares taught criminal procedure; gave talks in Philadelphia, Washington, Edinburgh, and Oslo; wrote journal articles; organized a conference, “Moving Justice Forward”; worked on a new book with Tyler and on a new edition of a textbook; and teamed up with two colleagues and her younger daughter for the Law School’s “Iron Chef” competition. Their egg- yolk raviolo won best entrée. Meares is always immersed in research, too. A current project allows people in low-income neighborhoods of five US cities to talk to each other, live, via huge video screens. After 1,000 interviews, Meares and Johns Hopkins professor Vesla Weaver will analyze the discussions of the question “How do you feel about police in your community?” To cope with all this work, Meares has set policies. She shops for clothes once a year, right after the July board meeting of Chicago’s Joyce Foundation; the meeting coincides with a big sale at Nordstrom’s. The nanny buys groceries, and a housekeeper cleans. “I don’t do anything myself that will take time away from my kids if I can pay somebody else to do it,” Meares says. Her five children—three from her previous marriage and two from her partner’s—range from a sixth-grader to a college junior. Her partner is Benjamin Justice ’93, a historian at the Rutgers University Graduate School of Education and an affiliate of the Justice Collaboratory. The two aren’t married, but after three years together, they hosted “a nonsectarian, non–legally binding—but still kind of romantic—celebration of our preexisting quasi-marital relationship.” (Now it’s been seven years.) The children stay with their other parents from Wednesday through Friday and on alternate weekends. That’s when Meares concentrates her work and traveling. When Obama White House counsel Neil Eggleston asked her to join the president’s policing task force, Meares told him she’d serve only if meetings were scheduled for days when the children were away. Eggleston consented. Meares recalls: “He said, ‘It’s not going to take much time.’” He was wrong, she says. Does she have any hobbies? “Hobbies?” she asks. “That’s hilarious.” But she does keep a greenhouse, and she likes to cook.

On an afternoon in March, Meares met with four dozen teenagers and 35 police recruits at an indoor basketball court in New Haven. The students were participating in a leadership program called LEAP, and the police came from the New Haven Police Academy. The two groups would meet together for six months, closing the program by serving meals together at a soup kitchen. Meares outlined the basics of procedural justice, and then she asked the students how they viewed police. One teenager replied, “You’re taught as a kid not to interact with police.” Another said that when police show up, “Someone is going to get arrested, or beat down, or killed. That strikes fear into our hearts.” Meares says reconciliation could begin before a cop says a single word if police dispensed with “command presence”—the rigid shoulders, oblique stance, and tense jaw that neither invite conversation nor suggest mutuality. One recruit challenged Meares: “If I show a little of my personality or kindness, am I going to sacrifice my safety?” and she added, “I apologize, because this is the way we were trained.” “It’s the way you were trained,” Meares replied, “but it’s not the best way. That’s not opinion. It’s research.” Meares pointed out to the teenagers that sometimes police chiefs order officers to carry out policies they oppose. “I’ve talked to cop after cop, and they all said, ‘We didn’t want to do that. We thought it was bad for the community.’” To the police-in-training, Meares suggested not only practicing procedural justice, but also demanding it from their superiors. “As officers, you should be treated justly, too. Your family needs you to be whole when you go home. Your community needs you to be whole. We all need you to be whole.” Meares pointed out that both policing and living in poverty exact a cost. “You have two groups of people who are experiencing trauma in an interaction. That’s not good,” said Meares. “Hurt people hurt people.”  Chart: Mark Zurolo ’01MFAStatistics from a 2016 survey of US adults by the Pew Research Center. View full imagePolice in the United States kill 1,000 civilians every year. (Roughly 50 on-duty police officers die in violent encounters.) Meares believes that any death caused by police demands far more than expressing sorrow and promising to check whether police broke a law. She wants communities to respond to each death caused by police in a way similar to the way the FAA investigates a plane crash, scrutinizing every error, every policy, every factor that might have contributed. There’s more: Meares argues that “A commitment to preserving life . . . will necessarily rewrite the aims of policing.” That will require civilians and police to confront a question that Meares asks often: “What are police for?” The answer, she says, will vary from place to place; police serve in 16,000 independent departments, and each community will need to decide what it wants from local police. Citizens and police will “co-produce” public safety. Police would benefit from such collaborations, says former police chief Ronald L. Davis, who headed the community policing office in Obama’s Department of Justice. “We’ve asked them [police] to define their job for themselves,” he says. Meanwhile, that job becomes increasingly complex. “The new generation of officers now have to be analytical, they have to be community-engaged, they have to understand mental illness, they have to understand the teen brain, they have to understand the difference between addiction and crime. They have to carry Narcan [to treat opioid overdoses] and refer people to substance-abuse treatment.” It’s unrealistic to ask police to do all this and also cultivate relationships with civilians, says Jim Pasco. Pasco serves as senior adviser to the head of the Fraternal Order of Police, the nation’s largest police union. Pasco says he values community policing, but he adds, “Police [departments] are so short-staffed and so underequipped that they find themselves running from call to call, and virtually everyone they meet is a stranger.” We can’t expect a “happy outcome,” he adds, “if we just send police officers into this toxic stew that exists in many cities in the United States, where citizens are prisoners through no fault of their own, caught in this cycle of hopelessness caused by poverty, failure of the health system, lack of educational opportunities, and lack of a mental-health safety net—all the direct responsibility of the elected officials who have failed these people for generations.” Meares agrees that improving police-community relationships is part of a bigger project. “Reducing crime is not just about these individual-level interactions between police and people. It’s about making sure that the institutions of city government serve the public.” Will the changes that Meares advocates take hold? Some in police leadership believe they will. Although President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions are pushing for a renewed “tough on crime” approach, Davis doubts they’ll get traction. “I’m hearing police chiefs say, ‘No thank you.’ Once the field has seen the value” of reform, he says, no administration can stop it. “They may take a handful of people with them, but the rest of us are going forward into the twenty-first century.” Former New Orleans police chief Serpas says that “Very few, if any, experienced and forward-looking police chiefs see any value in returning to the practices and strategies of crime fighting from the mid-1990s to today. ‘Tough on crime’ policies do not work.” Meares has no doubts. “Research shows that cops become cops because they want to help people. They’re pretty idealistic people,” she says. “I’m totally optimistic about police reform.”

|

|

4 comments

-

Dionne Hardiman, 5:18pm January 07 2018 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Dionne Hardiman, 5:29pm January 07 2018 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Chris Keevil, 5:02pm March 19 2018 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Booker Vance, 10:51pm June 23 2019 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.I am degreed and wonder if ypu would use my profile as a case study. I have had an interesting life

I am a degreed woman of color who has been victimized and the police did not act. I have been molested raped domestically ase studybused and these individuals broke in repeatedly. I have been hurt by different ethic peoples including black. Please use my situation as a case study.

That's a really nice article. I like the clarity with which you lay out a new approach to policing, and the details of about Tracey Meares and her life. She sounds like a really interesting person. It's also a hopeful article -- nice to hear that people are working on how to make policing better.

Praying fr my sister. Wonderful gifted talent.