loading

loading

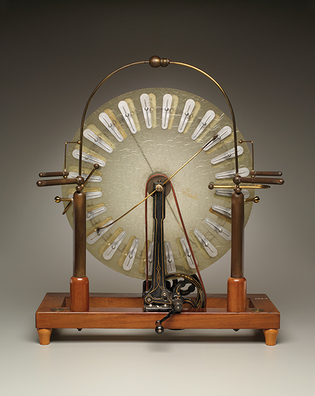

Arts & CultureGlass that shockedObject lesson: A nineteenth-century “influence machine” was a teaching tool about electricity. John Stuart Gordon is the Benjamin Attmore Hewitt Associate Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Yale University Art Gallery.  Yale Peabody Museum of Natural HistoryThe Wimshurst machine was a nineteenth-century electricity generator—of static electricity only, and only for study or enjoyment. This one was probably used in a classroom at Yale. View full imageThe late-nineteenth-century device pictured here is a Wimshurst influence machine, made of glass, metal, and wood. It was designed to produce static electricity, not for use as electrical power, but to demonstrate the properties of electrostatic energy. Other kinds of electrostatic generators had been used since the eighteenth century to demonstrate the properties of electricity—often in the parlors of the wealthy, where the shocks and sparks they produced thrilled partygoers. Between 1880 and 1883, the British engineer James Wimshurst invented this version. The broad glass discs, with mounted metal strips, spin in opposite directions; they produce an electrical charge, which is conducted through a pair of capacitors and then forms a dramatic spark as it leaps through the air from one metal sphere to another. This example, in the collection of historical scientific instruments at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, is featured in the new book American Glass: The Collections at Yale. The glass objects it presents, drawn from collections throughout Yale’s campus, tell the rich story of glass in American life from prehistory to the present. The diverse range of material includes luxurious table wares, decorative windows, plate-glass photographs, and scientific equipment. The inclusion of an electrical generator in a book on glass may seem unusual—but glass had a critical role in the instrument’s operation. Glass is nonconductive; therefore, the charge generated by the moving discs does not disperse. It is neutralized by pairs of metal brushes and then channeled by collectors into the circuit that produces the spark. By the end of the nineteenth century, Wimshurst’s invention had become one of the most prevalent electrostatic generators because of its straightforward design. Even amateur scientists could replicate it at home. Published guides, such as Alfred W. Marshall’s The Wimshurst Machine: How to Make and Use It, explained which materials were most appropriate:

Clearer glass worked best because green glass might have been colored with iron or copper metals, which could potentially conduct electricity. Once selected, the discs then needed to be shellacked, using button lac, until they were a pale amber in color. Finally the metal strips, called sectors, were affixed.

This wimshurst machine was professionally assembled in Germany and shipped to the United States, where it was sold by James W. Queen & Co., a prominent manufacturer and importer of scientific apparatus in Philadelphia. The firm supplied amateurs and educators alike with a wide range of tools for demonstrating all aspects of the physical sciences. The electricity section of their 1884 catalogue offered only Toepler-Holtz machines—the precursor to Wimshurst’s invention—but by the end of the decade Wimshurst influence machines were in wide circulation. In 1889 Washington University in Saint Louis boasted of their “small [Wimshurst] machine mounted on a polished mahogany stand about a foot or 18 inches in height, and . . . provided with 15-inch glass plates, brass conductors, and silver-plated contact studs. It is beautifully constructed and excited the admiration of the class.” The example shown here likely began its life in a similar classroom at Yale. It would have delighted and educated students before entering the Peabody’s collection as an elegant document of our continued fascination with electricity and the importance of glass in scientific experimentation.

The comment period has expired.

|

|