loading

loading

featuresFirst.As Yale seeks out more students whose parents didn’t graduate from college, students and alumni talk about the challenges that come with that pioneering role. Some hold major roles in higher education, like Yale’s senior vice president for operations, or the Harvard professor who became president of Morehouse College. Some are judges, including one who sits on the US Supreme Court. Some entered business—PepsiCo, Disney, McKinsey. An extraordinary array of Yale graduates were first in their families to earn college degrees, blazing a trail into academic and professional achievement from a background in which higher education was more a pipe dream than a given. In recent years, Yale and other selective schools have been recruiting and admitting ever greater numbers of these high-achieving “first-generation” college students. This fall, nearly one in five first-years at Yale are first-generation. But being the first in your family to attend college can bring a wide range of challenges. Terms like “syllabus,” “office hours,” and “fellowship” may be unfamiliar to anyone whose parents had no experience of college. Many first-gens say they feel like impostors amid classmates who have more money and more academic preparation. Many feel caught between two worlds. “Some of these students are thinking, ‘My brothers and sisters are at home, struggling to put food on the table, and here I am in a residential college with a gym and a pottery studio,’” says Burgwell Howard, Yale’s associate vice president for student life. Writer Elisabeth Anton ’89 recalls that when she was at Yale as a first-generation college student, she “didn’t want anyone to know that my grandparents were illiterate or that my father came from Cuba with only a high school education.” Yale, and a dedicated group of first-generation Yale alumni, hope to change campus culture so that first-gens no longer feel they have to conceal their identity.

Bob HandelmanA panel at the 1stGenYale conference, chaired by Jack Callahan ’80 (right), discussed nonprofits and public service. Panelists included (left to right) Paul Whyte ’93, Esther Addo ’07, Regina Bain ’98, ’01MFA, and Aaron Shipp ’96. View full imageSome first-gen Yale alumni say that, despite everything, they felt welcomed and at home on campus. “It was like going from Bumblesnap to Hogwarts, and it was nothing short of a miracle,” said Aaron Shipp ’96, who was the first person from his rural county in North Carolina ever accepted to Yale. “I fell in love with this place. I felt I belonged.” As a senior, Shipp held the post of freshman counselor; that year he lived in the opulent Vanderbilt Suite, built for Vanderbilt family members attending Yale. After graduating, Shipp worked as an actor, a banker, and a career coach. Then he founded a college-admissions consulting firm, The Ivy Edge, and a nonprofit—Y-Apply Inc.—that helps talented public school students apply to top-tier colleges. “It’s part of my wish to pay it forward,” he said. “I rarely felt out of place at Yale,” said Jack Callahan Jr. ’80, whose grandparents immigrated from Ireland to New Haven, and whose parents’ education didn’t go beyond Hillhouse High School. “Once in a while a topic would come up that I was clueless about. I remember a conversation on types of wine, and all I understood was white versus red.” Leaving Yale was more of a challenge: “While I wanted to go into the business world, I had no concept of what industry or job to pursue, as I grew up in a blue-collar family.” Ultimately, he earned an MBA from Dartmouth and served in key roles at McKinsey, GE, PepsiCo, and other major companies before becoming Yale’s first senior vice president for operations in 2016. Shipp and Callahan were among dozens of Yale alumni who spoke at a conference last spring organized by 1stGenYale, an alumni group that works to link first-generation Yale students with first-generation Yale graduates. Many who attended the conference remembered harder paths. “I was afraid everybody would be like Thurston Howell III without the ascot,” said Karin Kricorian ’94. “I felt like Yale was doing me a favor. I was afraid to do anything. The notion of trying out for a singing group was like going to Saturn.” Nevertheless, Yale changed her life, she said: she went on to Stanford business school and is now the director of management science and integration at Disney. For students from other countries, there were often additional burdens. Marta Moret ’84MPH, president of a New Haven public health consulting firm (and wife of Yale president Peter Salovey ’86PhD), described the pain of living in two cultures. She was born in Puerto Rico, where her father had left school in third grade, but she grew up in the South Bronx. “My parents wanted me to excel in this new world, but they thought, ‘She’s assimilating too fast,’” Moret said, in her moving keynote speech. She was accepted to Bennington College, where she hoped to become a writer—but her parents insisted she live at home until she got married. Moret agreed and attended Western Connecticut State University. However, she also insisted on dating. “My father didn’t speak to me for five years,” she said. Moret was plagued by self-doubt: “As I sat in [Yale’s] public health school, I thought, ‘Do I deserve to be at Yale?’” When she became Connecticut’s deputy commissioner for social services, she recalled, “I thought, ‘I’m a phony and somebody’s going to find out.’ Now I’m an adjunct [Yale] professor. I run my own consulting group. And I still feel like a phony. It’s a recurring theme for first-generation students.”  Bob HandelmanUS Magistrate Judge Peggy Kuo ’85 View full image“I was not only carrying the hopes of my parents on my shoulders, I was carrying the hopes of 23 million people on Taiwan and 2 billion Asians,” said Peggy Kuo ’85. Kuo was born in Taiwan, but her family moved to upper Manhattan; nine of them shared a two-bedroom apartment. She learned English at Head Start. “My mother told me and my sisters, ‘We are not rich and you are not beautiful, so you’ll have to get by on brains and hard work.’” Kuo said she “doubled down” on hard work at Yale, graduated summa cum laude, and got into Harvard Law School. “I thought, ‘We’re good, right? I’ve finally caught up.’ But I had to assimilate all over again” at Harvard. Ultimately, Kuo turned down a lucrative law firm offer and joined the US Attorney’s office in New York. “My mother said, ‘You’re turning down a job, to earn less and work harder as a prosecutor?’” But Kuo went on to prosecute civil rights cases around the country, investigate rape and sexual assault in Bosnia as part of a war crimes tribunal, and, in 2015, become a US magistrate judge in New York. Today, she said, “The world is changing. I can embrace being both Asian and American.”

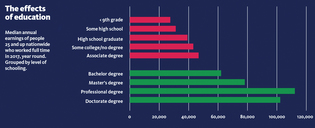

Bob HandelmanUrban Strategies president Marta Moret ’84MPH View full image Source: US Census Bureau, current population survey, 2018 annual social and economic supplement.View full image Source: Yale College Admissions Office.View full image Source: Yale College Admissions Office.View full imageEighteen percent of the entering Yale College Class of 2022 are first-generation students. That’s up from 12 percent in the class of ’17 and the highest percentage since Yale officially began keeping track in 2006. (While the percentage was likely much higher in Yale’s early days, monitoring first-gen status was not always clearly defined as an institutional priority for Yale, an admissions office spokesman said in an e-mail). It’s also notably larger than the percentage of legacy students: about 12 percent of the class have parents who went to Yale. The percentage of students from low-income families—at least, those who qualified for federal Pell Grants, based on their family’s resources—has also increased, from 12 percent to 20 percent in the last five years. The two groups overlap significantly. (The low-income figure doesn’t include international students, many of whom come from families with modest means but can’t apply for Pell grants.) The push for highly selective colleges and universities to enroll more first-generation and low-income students has been growing for more than a decade. One major influence was the 2005 book Equity and Excellence in American Higher Education, by the late William G. Bowen and others. The authors examined a wealth of data and concluded that “there is much more progress to be made” in opening higher education to students—often poor, first-generation, or minority—whose families haven’t already made their way to college. Vassar and Amherst were two of the quickest to act, rapidly increasing their numbers of first-gen and low-income students. Other highly selective schools are also recruiting and accepting more students from nontraditional backgrounds. This year, first-gen students made up 14 percent of U. Penn’s admitted freshmen, 15 percent of Dartmouth’s, 16 percent of Princeton’s, 17 percent of Harvard’s and 18 percent of Stanford’s. Nationwide, about 33 percent of students enrolled in postsecondary education have parents who did not attend college, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. That’s down from 37 percent in 2000, largely because more Americans in general have attended college in recent decades. Prominent first-gen college alumni, including former First Lady Michelle Obama, Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, and US Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor ’79JD are also speaking about their own backgrounds, serving as role models and encouraging more students to apply. At Yale, Salovey has made expanding economic and educational diversity a priority since he became president in 2013. “Our country and our world stand to benefit greatly from cultivating and supporting talented young people from every zip code, nation, and income level,” he wrote in a letter introducing the 1stGenYale conference. The push to enroll first-gen and low-income students—many of whom assume Yale is too expensive or wouldn’t be interested in them—required Yale to invest more time and effort in recruiting. (See “Wanted: Smart Students from Poor Families,” January/February 2014.) But it is evidently working. And once the applications are in, says Jeremiah Quinlan ’03, dean of undergraduate admissions and financial aid, the criteria for admission remain the same across the socioeconomic spectrum: “The first question we ask is, can they do the work? Then we ask, how have they contributed to their communities, their schools, their families, and how are they likely to contribute to Yale?”

Some first-gen alumni say they were unprepared for Yale’s academic rigors, despite being at the top of their high school classes. David A. Thomas ’78, ’86PhD, grew up in an African American community in a segregated area of Kansas City, Missouri. Neither his parents nor any of their combined 16 siblings had finished high school. “I showed up at Yale, and I had never written a paper longer than five handwritten pages,” he said, in a dinner speech at the 1stGen Conference. “I had never read Shakespeare. I took the highest math course my school offered. It was not calculus. But I came to believe that if I developed the habit of excellence, then things that were initially hard for me I could ultimately achieve.” Many Yale students, Burgwell Howard notes, “have been the first in their family to go to college—since 1701,” but until now, “we just didn’t think about the challenges and implications for those students, or actively encourage them to apply.” The university has recently started several initiatives to help more first-gen and low-income students afford Yale and to ease the transition for them academically and socially. The Yale College Dean’s Office has opened a new First-Generation/Low-Income Community Initiative Office, which will serve as a hub for resources for first-gen students. The office also plans to hold twice-weekly workshops on academic and social issues that first-gen students face. And Yale plans to expand its six-year-old First-Year Scholars at Yale program (FSY), which currently invites roughly 60 incoming first-gen and low-income students to a fully funded five-week immersion program on campus, so that they can acclimate early to Yale and make friends while taking English 114 and getting a head start on college calculus. Former FSY participants serve as counselors. “Just to hear former FSY students say ‘I was so scared when I came. Here’s how I navigated things,’ is extremely valuable to incoming students,” said Jeanne Follansbee, dean of Yale’s summer academic session. Students are also forming their own first-gen groups, with specific missions: A Leg Even, for example, helps students navigate their first year at Yale, and FLY (for First-generation Low-income at Yale) assists such students throughout their Yale careers. Most of Yale’s graduate and professional schools also have their own first-gen organizations, some of them focusing specifically on students who are the first in their family to get a professional degree. For Yale alumni, there’s 1stGenYale. Last spring’s conference was attended by more than 120 first-gen alumni, including CEOs, bankers, lawyers, entrepreneurs, scientists, artists, teachers, a federal magistrate, and an FBI special agent. The group is one of the Yale Alumni Association’s shared interest groups; it was founded in 2016 by Lise Chapman ’81MBA, who worked closely with Magda Vergara ’82, until recently her fellow cochair. “By telling our stories, as former students and now professionals in diverse careers,” says Chapman, “we can help current students to know that they are not alone. We all belong to the Yale family.” For some alumni, the conference marked the first time they had ever spoken publicly about being a first-gen college student. 1stGenYale also cohosts an annual “career mixer” with the Afro-American Cultural Center in November, where current students can talk with alumni in a variety of professions. The group is also developing webinars on topics such as the impostor syndrome and unconscious bias, and setting up a national network of Yale alumni who can serve as anchors for first-gen students arriving in new cities for summer internships or full-time jobs. It has a database of more than 975 Yale alumni, including some who were not first-gen or low-income themselves but are interested in a supporting role. While some alumni involved in the group still prefer not to identify themselves widely as first-generation graduates, “more alumni are feeling more comfortable sharing that they came from a first-gen or low-income background,” Chapman says.

Bob HandelmanEsther Zirbel ’93PhD moderated the 1stGenYale panel on “Challenges and Opportunities in STEM careers,” one of four panels organized for the conference. The day also featured speakers, “power networking,” and a “flipped classroom” discussion, in which the students did most of the talking. View full imageOne of the most difficult problems first-gen and low-income students face is money. Many alumni say that as students, they juggled numerous campus jobs—and lived in fear of “bursar’s hold,” a purgatory that students could fall into if their tuition bills weren’t paid in full by the start of each term. “You weren’t allowed to register for class or eat in the dining hall, so you really felt like you didn’t belong here,” said Kricorian. (Yale ended the practice in the late 1990s.) Other first-gen alumni remembered feeling isolated and struggling to make ends meet—often in secret, because they didn’t want to draw attention to their less-privileged backgrounds. At Yale, “I landed in with the beautiful people, because I could speak several languages, but I couldn’t afford to go clubbing in New York City or skiing in Aspen. I didn’t have a proper coat freshman year,” said Elisabeth Anton ’89. (Anton, who grew up in Latin America, began her career as a banker and is now a technical writer and translator in four languages. She is writing a book about the history of women at Yale.) Tim Ryan ’20, copresident of A Leg Even, says there is a persistent divide between students who have to work campus jobs and those who can spend more time socializing; and between those who can afford to travel on weekends and those who can’t. “This is what leaves students walking away with starkly different experiences and perceptions of Yale after four years,” says Ryan, a first-gen student from upstate New York who has worked since he was 14 years old. Other barriers are more subtle. Laura Plata ’19, a first-gen student in high school as well as at Yale, recalls discussing post-college plans with her suite-mates freshman year and telling them, “I’d have to get a job that could support my family financially.” One replied that her parents should be able to support themselves. “I was so shocked,” Plata says. “My parents sacrificed so much so I could be here. I didn’t know how to explain my world to someone who had gotten everything she’d ever wanted in life.” Yale has been working to address some of the financial problems. It requires zero financial contribution from families earning less than $65,000 a year. It now gives students from such families a $2,000 start-up grant in their first year, and $600 in subsequent years, to help cover expenses such as a laptop, books, and winter clothing. Starting this year, these students receive free hospitalization insurance as well. So that students on financial aid can take the same kinds of low or unpaid summer internships their wealthier peers enjoy, they can also apply for stipends to help cover their living expenses during those internships. Both the Dean’s Student Assistance Fund and the residential colleges have long had discretionary funds to help students who find themselves in sudden financial straits—or simply in need of a winter coat—on an ad-hoc basis. Yale is now developing an online portal called SafetyNet, where any undergraduate can apply for help with specific needs. “These funds already exist at Yale, but this will make the process of asking for help more equitable, more transparent, more consistent, and smoother for everybody,” says Rebekah Westphal, director of the office of fellowship programs, who is managing the project. The new First-Generation/Low-Income Community Initiative Office is also having conversations with first-year counselors about how to help students navigate awkward situations—such as when their suitemates are all kicking in $20 to go to Pepe’s for pizza, and they don’t have $20 to spare. Providing food for students who can’t afford to go home over school breaks has also been a persistent issue. Last year, Yale kept at least one dining hall open during fall and spring breaks. But it has yet to find a systematic way to feed and house low-income students when the residential colleges are closed as well. Financial-aid packages for some low-income and international students now include a vacation allowance, however, and, in some cases, Yale gets students lower rates at the Omni hotel. The aim of all these programs, says Howard, is to see “if we can systematically lower some of the barriers to success.” It’s not just practical issues, like money and food. Yale is also making an effort to help first-gen and low-income students recognize, and take pride in, the strength and resourcefulness they have already shown in getting to Yale—especially as they lack the family resources many classmates can fall back on. In short, rather than being born on third base, first-gen students really did hit a triple. As Camille Lizarribar, dean of student affairs, told the conference attendees: “In the Zombie Apocalypse, who would I want to be stuck in some place with? I’d pick you guys.” She added, “It’s not that you’re being invited to this place. You are this place.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|