loading

loading

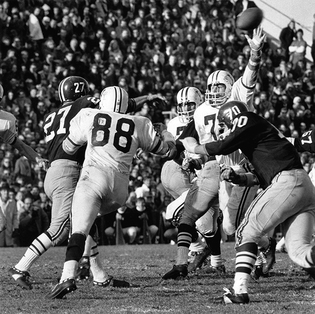

featuresThe tie that bindsFifty years after a stunning Yale-Harvard game ended in a tie, men who played in it still replay it in their minds. George Howe Colt is the bestselling author of The Big House, which was a National Book Award finalist and a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. This article is an adapted excerpt from his book The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968. Copyright © 2018. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.  Jerry Cooke/Sports Illustrated/Getty ImagesHarvard’s Pete Varney catches a two-point conversion pass, ending the 1968 Yale-Harvard game in a tie. View full imageNobody who lived through the 1968 Yale-Harvard football game has ever forgotten it. It is surely the most remarkable game in the long history of the rivalry—we’d say the greatest game, except that it’s hard for a Yale fan to characterize it that way. On November 23, the undefeated Yale team, led by Brian Dowling ’69 and Calvin Hill ’69, strode confidently into Harvard Stadium for the 85th edition of The Game. They faced a Harvard squad that was also undefeated. But to most observers, Yale looked unstoppable. And for most of the game, the Bulldogs performed as expected. At halftime, they led 22–6, and with less than four minutes left, they were still ahead 29–13. And then, in what the Yale Alumni Magazine described as “some incredible legerdemain,” the Crimson came back. With the help of two Yale fumbles, three Bulldog penalties, and a successful onside kick, Harvard scored two touchdowns in the final 42 seconds, tying the score 29–29. Since overtime was not yet a part of college football in those days, that was how it ended. The Harvard Crimson’s now-famous headline told the story all too well: “Harvard Beats Yale, 29–29.” George Howe Colt, son of a Harvard alum and eventually a Harvard graduate himself, was a 14-year-old in the stands that day, and—unlike many fans—he did not leave early. This fall, Colt’s book The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968 was published by Scribner. Based on research and extensive interviews with players, coaches, fans, and others who lived through the era, Colt’s book recounts in full the story of that famous game and the season leading up to it. But it also places the game and its principals in the tumultuous cultural and political context of its time. For the 50th anniversary of The Tie, we offer here an excerpt adapted from the epilogue of Colt’s book.—The Editors  Paul Connell/Boston Globe/Getty ImagesHalfback Nick Davidson ’69 carries the ball for Yale in the second quarter. The Bulldogs dominated The Game until late in the fourth quarter. View full imageFurred with dust, the football sits on the top shelf behind the counter at Leavitt & Peirce, the tobacconist on Massachusetts Avenue in Cambridge, that since its opening in 1883 has served not only as a purveyor of pipes, cigars, and backgammon sets but as a reliquary of Harvard sports memorabilia. It is one in a row of 23 footballs, each of which bears, in fading white paint, the date and score of a signal Crimson victory. The oldest, its leather cracked with age, dates from the 1898 Yale game, a 17–0 Harvard win. This ball, a time-softened Wilson “The Duke” model, bears the words:

Even as fans walked off the field that day, whether in agony or ecstasy, they knew they had witnessed something extraordinary. The following year, Sports Illustrated ranked the game among the ten most exciting in college football history. But as time went on, it would be remembered as more than just an exciting game. It would be remembered as a rare moment of grace in a tragic and turbulent year. At an intensely polarized time, in which the country seemed irrevocably divided—dove vs. hawk, black vs. white, young vs. old, student vs. administrator, hippie vs. hard hat—the tie between archrivals seemed a kind of truce. Indeed, the teams had unwittingly combined to create something like a work of art that would take its place in the iconography of the era. Not long ago, the former Yale linebacker Andy Coe ’70 happened to visit The 1968 Project: A Nation Coming of Age at the Oakland Museum, an exhibition examining that watershed year. There, not far from photos of a busboy attempting to comfort a dying Robert F. Kennedy and of Vietnamese civilians massacred at My Lai, was the image of Harvard tight end Pete Varney holding the ball aloft in the Yale end zone, with Coe himself in the background, looking stunned. Today, as they watch film of the game, some of the players still can’t believe it will end in a tie. Certainly, Yale’s school-record-tying six fumbles—three inside the Harvard twenty—were a primary factor in Harvard’s comeback. Certainly, too, the series of calls against Yale in the game’s chaotic final minutes played a role. (Yale coach Carm Cozza wrote in his autobiography, “There’s no doubt in my mind that the officials got caught up in the emotion of the game.”) And yet for the game to end the way it did required an almost otherworldly confluence of timely plays, questionable decisions, debatable calls, fortuitous bounces, and the kind of blind luck usually encountered only in fairy tales. And that was just the last three minutes. Actor Tommy Lee Jones, who played in the game, mischievously points out that if Harvard hadn’t botched the extra point after their first touchdown, they would have won 30–29. Indeed, it is tempting to wonder: what might have happened if Yale had fumbled five times instead of six? If Harvard’s Vic Gatto and Ray Hornblower had been at full strength? If Yale’s George Bass ’69 hadn’t been injured? If Yale quarterback Brian Dowling ’69 had passed one less time on Yale’s final drive? If Yale hadn’t called time out with a minute to play? If Cozza had put in Dowling and Calvin Hill ’69 on defense for those last 42 seconds? (Cozza, for one, maintained that if he had put them in, they would have found a way to stop Harvard.) Perhaps nothing would have made a difference. Many of the players have concluded that larger forces were at work during the game’s final minutes. Yale’s Brad Lee ’70 likens it to “a Greek tragedy unraveling.” Pat Madden ’69 talks of “the hand of God.” Harvard players use words like destiny, fate, and divine justice. Rick Berne has another theory. “It was karma,” he says. “That sounds silly, but I really think that the student movement and everything else that was going on at the time contributed to the camaraderie, to the vibe, to the success of our team. It gave us some perspective. Most of us weren’t focused single-mindedly on football. Which isn’t to say we weren’t just as dedicated to the team. But looking at what was going on in the world was part of the picture, and maybe part of the reason the game turned out the way it did.”

Frank O’Brien/Boston Globe/Getty ImagesYale’s Fran Gallagher ’69 tries to block a pass by Harvard quarterback Frank Champi. Champi came off the bench to lead the Crimson rally, throwing two touchdown passes and the tying conversion. View full imageEach November, as The Game approaches, highlights of the 1968 game appear on TV, the film looking as grainy and old-fashioned now as film of Albie Booth looked in 1968. Each November, the players get calls from sportswriters, asking the same questions. Each November, when alumni gather and talk of games gone by, the conversation inevitably turns to 1968. Harvard people refer to it as “the famous tie,” Yale people as “the infamous tie.” Neither side, of course, thinks of it as a tie. Former New York governor George Pataki ’67 writes, “I take some solace in the knowledge that Harvard considers a tie with Yale to be its greatest ‘victory,’ while Yale considers the tie with Harvard to be its worst ‘defeat.’” Fifty years later, Harvard players reflexively use the word win when they talk of the game; Yale players use the word loss. For Yale, the imperfect end to their perfect season took time to absorb. A few days after the game, the Harvard team invited their Yale counterparts to a joint Ivy League championship banquet. The Yale players voted, overwhelmingly, to decline the offer. There was nothing to celebrate. The wound was too fresh. Their own annual banquet, held that same week, was a somber gathering. It didn’t seem fair that a game they dominated for fifty-six-and-a-half minutes hadn’t resulted in a victory. Some of the players say that if the teams had played ten times, Yale would have won nine. Many Harvard players agree; Yale, they admit, was a far more talented team. “We were lucky to be on the field with them,” says Gus Crim.  James Drake/Sports Illustrated/Getty ImagesYale quarterback Brian Dowling ’69 led the Bulldogs for one of their greatest seasons, ending in a tie for the Ivy championship with Harvard. View full imageFor some Yale players, the sting lingered. “My friends joke that if I had an MRI right now, there would be a little lesion up there that reads ‘29–29,’” says Kyle Gee ’69. Over the years, however, most of them have made their peace with it. Indeed, Yale and Harvard players alike admit that if either team had won, they’d be the only ones who would remember the game. (Nevertheless, former Yale middle guard Milt Puryear ’71 admits with a rueful laugh, “I would have preferred to win—and have the game be forgotten.”) Almost everyone agrees that the chance of any future Harvard-Yale game eclipsing the tie of 1968 is impossible—and not just because in 1996 the NCAA changed its rules to permit overtime. Although no one realized it at the time, the 1968 game would be the last hurrah in the history of big-time Ivy League football. In 1982, the NCAA demoted the league from Division I-A, college football’s top stratum, to the less competitive Division I-AA. Harvard and Yale continued to recruit talented prospects—since 1970, 51 of their players have gone on to play in the NFL—but would never again compete in the rankings with Alabama and Nebraska. These days, they fight for standing in the polls with Lafayette and Central Connecticut State.  Frank O’Brien/Boston Globe/Getty ImagesWith no time remaining on the clock Harvard’s Vic Gatto (No. 40) catches a pass for a touchdown, making the score 29–27 and setting up the tying conversion. View full imageWith the demotion to I-AA and the meteoric rise in popularity of professional football, game attendance has fallen precipitously. In the 1990s, faced with a dwindling fan base and a deteriorating physical structure, Yale considered tearing down the Bowl. Although in the end the decision was made to renovate, the Bowl—and Harvard Stadium—can look almost deserted on Saturday afternoons in the fall. Newspaper coverage, too, has shrunk. Five decades after devoting half the front page of its sports section to the 1968 game, the New York Times (which, like Harvard and Yale themselves, has become more meritocratic) relegates the annual contest to a few short paragraphs on page two. The game, however, remains The Game—“the last great nineteenth-century pageant left in the country,” as former Yale president A. Bartlett Giamatti ’60, ’64PhD, called it. It still sells out Harvard Stadium and nearly fills the Bowl. It is the one game students still attend, the one game around which alumni schedules still revolve, the one game still guaranteed to stir the blood, whether it runs crimson or blue. J. P. Goldsmith ’69, a retired investment banker and Yale’s starting safety in 1968, still gets goosebumps just before the game when the Yale Precision Marching Band forms its traditional (and slightly less than precise) “Y” at midfield, and launches into “Here’s to Good Old Yale,” followed by “Bulldog,” “Boola Boola,” and “Good Night, Poor Harvard.” He sings along with gusto, in a voice that grows a little thicker with emotion with each passing year.

The comment period has expired.

|

|