loading

loading

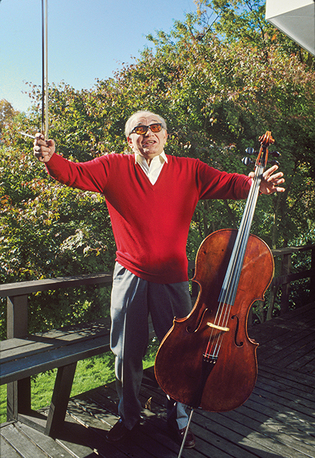

features"Irascible and difficult." "Very intense." And beloved.Aldo Parisot was one of Yale's most famous musicians. He was also, possibly, its most idiosyncratic personality. Composer and pianist Matthew Guerrieri writes for the Boston Globe. He is the author of The First Four Notes, a New Yorker Best Book of the Year.  Courtesy Aldo Parisot EstateAldo Parisot, who died on December 29, 2018, was a world-class cellist and for 60 years a faculty member at the Yale School of Music. He is shown here in earlier days with his Stradivarius. View full imageThe curiosity never flagged. When I visited Aldo Parisot ’48Mus in his house in Guilford, a couple of weeks after his 100th birthday, a good portion of that century seemed to surround him, the accumulated evidence of a cornucopian life: honorary degrees, musical souvenirs, collected curios. He sat on the couch, under one of his own paintings, a bright, bold abstract dedicated to his wife Elizabeth; other Parisot paintings dotted the walls, the doors, the chairs. The house was a storehouse of possible stories. But Parisot’s curiosity instead settled on a bit of arithmetic: how many days has he been alive? Thirty-six thousand, five hundred and forty-four, more or less. Even the math could only get so close. The day of Parisot’s birth—September 30—was recorded, but not the year. As a young and already-celebrated cellist in his native Brazil, Parisot, like so many prodigies, had a year or two shaved off to make his achievement seem more impressive, a year or two tacked on to allow him entry to adult employment. Published sources put his birth year anywhere from 1918 to 1921. (Government documents, beginning with his 1946 arrival in the United States, consistently favor 1918.) A hundred years was as plausible a duration as any, perhaps even a bit short, given Parisot’s filled-to-capacity life, as a world-class performer, as a teacher, as a visual artist, as a seemingly endlessly renewable source of gusto. Still, the elusiveness of an exact number somehow seemed appropriate. On that day in October, retired after 60 years on the Yale faculty, Parisot bounced from topic to topic, still looking for something to pique his curiosity. Appropriately, the most fruitful subjects were all, in a way, moving targets—conversation about aspects of music and life that resisted easy summation. He enjoyed the pursuit. “You are always looking for the answer,” he said. “It’s what keeps you going in this goddamn business.” We talked for a couple of hours. Parisot did as much interviewing as answering; the opportunity to have a sounding board, even a sparring partner, was too good to pass up. (“I classify people,” he warned, “by how they talk.”) Elizabeth Parisot—herself a proficient musician, a pianist, a Yale alumna and professor—cheerfully popped in and out, displaying all the qualities of a skilled accompanist: cueing entrances, filling in the conversational line with additional prompts and details, offering reminiscences of her own. I wasn’t the only visitor that day. Ole Akahoshi, a fellow cellist and Yale faculty colleague, was coming by later that afternoon. A couple of months later, on December 29, Aldo Parisot passed away. Can the death of a 100-year-old come as a surprise? Parisot’s did, to me. He had slowed down, certainly. A fall had limited his mobility. He had good days and bad days, I was told. But, on the day of the interview, Parisot again and again showed a restive spark, a sense of forward motion only temporarily interrupted. As we talked, even a triple-digit birthday simply felt like another extraordinary event in a life that had an endless capacity for them. Over the previous weeks, I had flooded my ears with his playing, surveying a catalog of recordings showcasing his fierce elegance, his assertive, pervasive sound. In person, one could still see where the performance and the performer converged. He was reflective; he was feisty. He was still, after a century, looking for the answer.

Courtesy Aldo Parisot EstateThe young Parisot in his homeland, Brazil, in a quiet moment for the camera. View full imageFall weather had arrived in Guilford; Parisot was not exactly a fan. More than seven decades of North American winters had served only to amplify the appeal of his remembered homeland. “In north Brazil, the temperature goes from 78 to 80 degrees—all year round!” he marveled. “There’s no swimming pools, there’s the ocean. And it’s the most beautiful place.” He was born in Natal, capital of the state of Rio Grande do Norte. When Parisot was four, his father died; soon after, his mother married Tomazzo Babini, an Italian cellist who had found Natal to his liking, settling in the city to teach at the local conservatory. Parisot heard Babini’s playing and was entranced, and began to pester his parents for lessons. They eventually relented—perhaps the earliest recorded example of Parisot’s characteristic tenacity. Babini’s teaching was decidedly old-fashioned. The foundation was strict: two years of solfège, sight-singing, and rhythmic training. The materials conformed to late-nineteenth-century ideals. Newer music was not part of the curriculum, nor was much of the music of the Baroque. (It would be years before Parisot crossed paths with the cello suites of Johann Sebastian Bach, now the bedrock of most cellists’ repertoire.) But Babini enabled his stepson’s fearlessness. Most beginning cellists start learning in the easiest position, the fingering hand closest to the top of the instrument. Parisot began with advanced technique: thumb position, high up on the fingerboard. From the start, he was equipped to approach difficulties with aplomb. By the time he was 12, Parisot was performing a Haydn concerto with an orchestra in Natal. At 16, he had a job performing on the radio. Parisot was soon something of a star all over the north, his concerts and appearances announced and promoted in newspapers with an air of local pride: “Our young and applauded artist,” one 1936 notice read. (The coverage helped establish the fog around his age: for a number of years, Parisot was routinely reported to be 14.) He began to teach—earning the title “Professore” in his newspaper mentions. He toured. He joined the newly formed Orquestra Sinfônica Brasileira. His ambition, though, kept him eyeing the horizon. A 1942 offer to come to the United States to study with legendary cellist Emanuel Feuermann was scuttled by Feuermann’s untimely death. Four years later Parisot was offered an opportunity to study at Yale, and he jumped at the chance. “You can’t stay. You can’t quit,” he reflected. “You have to go where you can be the most successful.” Several papers in north Brazil found his departure newsworthy enough to mention. By the late 1950s, Parisot had checked off one goal after another. He had established himself professionally, becoming the principal cello of the Pittsburgh Symphony, then leaving that group to pursue an international career as a soloist, tallying up appearances with leading orchestras in the Americas and abroad, tirelessly touring. He had put down roots, marrying Ellen Lewis ’50ArtP, an artist and teacher, and having three sons. (That marriage ended in the 1960s, but Parisot still, unprompted, boasted about his sons: film director Dean, architect Robert, and sculptor Ricardo.) And, in 1958, he joined the Yale faculty.

Robert A. LisakParisot had an exuberant and feisty personality, which several Yale composers sought to capture in the music they wrote for and about him. View full imageSuch a kaleidoscopic career would, naturally, resist being summarized in a single interview. Instead, we talked about modern music. Warhorses, the standard pieces in the classical repertoire, might have been a mainstay of Parisot’s performing career (“I was playing Dvorak, Haydn, Boccherini,” he said, “because”—at which point he rubbed his fingers together), but that curiosity, again, led him to new music. Brazilian composers, of course: Claudio Santoro, Camargo Guarnieri, Heitor Villa-Lobos. (All three would write cello concerti for Parisot.) And, once he was settled in his new home, American composers as well. His appointment to the Yale faculty proved especially fertile in this regard. Most performers would be thrilled to have a single piece named for them. Parisot had five, all from composers who taught at Yale. The first made a substantial splash: Donald Martino’s 1964 Parisonatina al’Dodecafonìa. In the summer of 1966, Parisot was asked to perform the work at Tanglewood’s Festival of Contemporary Music. Elizabeth Parisot ’73DMA remembered the occasion, Parisot racing the two of them from Connecticut to the Berkshires in his red Karmann Ghia—“in the fog,” she emphasized—Parisot playing the piece, then immediately speeding back for a colleague’s birthday party. (“I’ve only ever seen Tanglewood from backstage,” Elizabeth noted.) The next morning, Martino called, asking if they had seen the reviews. The Parisonatina was the hit of the festival, with Parisot’s playing described with awe by critics in Boston and New York. The piece is both feverishly complex and feverishly expressive. Martino turned Parisot’s name into a musical motto, then proceeded to recombine and deconstruct that material into breakers of sound, couched in the 12-tone vocabulary referenced in the title. Multiple streams of musical consciousness seem to charge through the work, including the performer’s: the final section offers the possibility of improvisation. In anticipation of my visit, Elizabeth had pulled out her husband’s copy of the score, with various phrases and passages notated in different-colored inks, like different lines on a subway map. The Parisonatina is a tall order for any performer, demanding a player with enough technique and imagination to balance the work’s extroverted drama with its cerebral, even esoteric theoretical complications. Parisot described Martino, who died in 2005, in similar terms, both immediate and elusive. The two men could bond over off-color humor. “He had the most amazing collection of dirty jokes,” Parisot noted, in a tone both impressed and jealous. “I have a large collection of dirty jokes, I’m Brazilian”—ribaldry being the country’s unofficial social currency—“but his: I’d never heard such language before.” They shared a similar drive; Martino “was a locomotive. He would write and write,” Parisot said, demonstrating by furiously scribbling on imaginary paper. But, at the same time, “he was very reserved. He was outgoing, but you would talk with him for a long time, and still feel like you didn’t really know him.” In a similar way, Parisot acknowledges the Parisonatina’s challenge while, at the same time, celebrating the work’s vitality: “it’s very difficult,” he said, shaking his head, but also, “it’s a shame that this kind of music isn’t being written anymore.” Parisot was parsimonious about teaching the Parisonatina. One of the few students to take it on was Ashley Bathgate ’07MusAD, who completed both a Master’s degree and an Artist Diploma in Parisot’s studio. “It was his suggestion for me to learn it, and from what I understand that wasn’t a suggestion he made very often,” Bathgate recalled. But her enthusiasm for contemporary music caused Parisot to recognize something of a fellow intrepid soul. Bathgate’s energy was defined in characteristic Parisot terms: “He used to say that I was ‘full of beans.’” Even for Bathgate, accustomed to working with composers, the venture was unusual: working on a piece not just with its dedicatee, but with the person the music is meant to, in some way, portray. The Parisonatina “is very much about this vibrant personality, Aldo Parisot,” Bathgate says. “But he let me take the reins and make it my own and figure out my own path through it.” One of the few specifics Parisot insisted on was, appropriately, a theatrical touch. “I remember him talking about that piece and how he premiered it, and he said, ‘Actually, you must, you must, stand upright when you finish that piece,’” she says. “And, yes, I did jump out of my chair when I did it!” The coaching embodied the paradox of Parisot’s teaching, suffused with his own strong musical presence and exacting standards but focused on students developing their own style. When I asked him about the task bringing out a student’s personality, Parisot was sharp: “They give up too soon!” Technique is not enough; a performer needs zeal, a zest for experience, and a love of the journey. “How can you know all about life when you’re 20? Wait until you’re 75,” Parisot commanded. “Then, maybe.”  Courtesy Aldo Parisot EstateParisot took up painting in the 1940s and never stopped. View full imageThe other works bearing Parisot’s name were composed for the Yale Cellos, the student ensemble that Parisot founded in 1983, and conducted up until his 2018 retirement. Even before the Yale Cellos, Parisot had made opportunities to conduct groups of cellists, especially in music by Villa-Lobos, whose Bachianas brasileiras nos. 1 and 5 remain at the center of the cello-ensemble repertoire. When Ezra Laderman wrote his first piece for the Yale Cellos, he took inspiration from both Brazilians: Aldo, composed in 1994, spun a set of variations on a folk song that Parisot remembered his mother singing to him, in styles that often echo the sinuous mass of Villa-Lobos’s exercises in the genre. A second work, Parisot, from 1996, put its namesake in historical company, with movements inspired by the great cellists of the twentieth century—Gregor Piatigorsky, Pablo Casals, Emanuel Feuermann, János Starker. The finale, of course, was Parisot: a moto perpetuo marked “Vivace” and “very intense.” Again, Parisot likened the music to its creator, with Laderman’s more straightforward musical language, in his ear, echoing the composer’s easygoing personality. Laderman, a former Yale dean who continued to teach at the School of Music until just before his 2015 death, occasionally stood up for his conceptions in the face of Parisot’s (presumably insistent) technical advice, but always with an apologetic air. “He would say, ‘Should I change this? Make it easier?’ And then he would say, ‘I think I’m going to leave it the way it is.’” Parisot, having said his piece, could shift into magnanimity: “Go ahead! It’s your property.” In 1998, Laderman made it a trilogy of works with another work entitled Simões, Parisot’s middle name. If his previous portraits emphasized Parisot’s alternately urbane and fiery exuberance, Simões reaches for something more enigmatic, even mystical. The music, rich but elusive, is, perhaps, a hint that Parisot’s single-minded devotion to the cello might well go by another name: faith. Parisot was familiar with the ways of faith. He grew up steeped in Brazilian Catholicism; two of his aunts, he noted, were nuns. The tradition followed Parisot until the end. “I believe in Jesus Christ,” he said, matter-of-factly. “I believe he came here, told us what to do, and then went away. And now it’s up to us to do what he said.” How does music fit into that obligation? “It doesn’t! Music is off in a corner. It doesn’t fit anywhere. But it’s there.” To try to rationally justify faith—whether in the divine or in music—was to somehow miss the point.

Courtesy Aldo Parisot EstateParisot pushed his cello students to deliver an enormous sound. Here, in a lesson with Steven Barrett Sills ’78, ’78MusM, he’s evidently urging a more dramatic bow stroke. View full imageMartin Bresnick’s Parisot, premiered in 2016, makes room for another side of the man: his confrontational single-mindedness. “He gave me very explicit instructions on what I was supposed to do,” Bresnick remembers. “He started telling me all the different things that he wanted to have happen in the piece.” Parisot asked his Yale colleague for something in the Baroque style; something like, he said, the famous Tomaso Albinoni Adagio—a work that, far from being authentically Baroque, was instead almost certainly the creation of a twentieth-century musicologist. “That’s a made-up piece,” Bresnick pointed out. “I know,” Parisot answered. “But you know what I mean!” Parisot continued to suggest, demand, cajole. When Bresnick finally suggested that Parisot write the piece himself, Bresnick recalls, Parisot shifted to blandishments: No, Martin, you are the composer. The insistence carried through to the performance: Bresnick conducted the work’s premiere, but the prime mover of the Yale Cellos still left his stamp on the performance. Parisot “told me that I was a terrible conductor, and I said, ‘What am I doing?’—you know, help me out here,” Bresnick says, laughing. “He said, ‘You’re terrible because you don’t tell them they play like shit!’” It was a prime example of a Parisot trademark: the unfiltered spleen that somehow only further endeared him to coworkers and collaborators. When Parisot retired, Robert Blocker, dean of the Yale School of Music, acknowledged that barbed style of encouragement. “His strongly held opinions about artistic excellence . . . led generations of faculty and students to carefully consider their points of view about music making,” Blocker noted, with diplomatic grace. “But with his rigorous intonements came a palpable love for the beauty of music and what it means to our lives.” Such brusqueness informs the work’s first movement, titled “Paradox”: a grand, intense procession embodying the conundrum of Parisot’s temperament, how someone who could be so “irascible and difficult,” as Bresnick notes (“I had terrible fights with him on committees”), was nevertheless so beloved. The second movement, “Parallels,” a slow-shifting tattoo of pizzicato, is, perhaps, testament to the persistence of that affection—the patient tick of years working alongside each other. Both movements, the one fiercely bowed, the other forcefully plucked, channel a Parisot trademark: volume. The cello has a reputation for sonic reticence, a trait that, over the centuries, has caused more than a few composers to sidestep its potential as a solo instrument. (“I’m not sure I would write for it!” Parisot joked.) But his playing made such concerns moot. Parisot’s enormous, booming sound never became harsh, always retaining clarity. It is one thing that he demanded from all his students, whatever their personalities. Gathered together in the Yale Cellos, the result was a steamroller of sound. (“They’re like trombones,” Bresnick says. “I mean, they could knock you right off the stage, any one of them.”) But Bresnick’s final movement, “Paragon,” turns inward. The title refers to an ideal, a touchstone, but also, maybe, the distance between that ideal and the real, vital, unpredictable person embodying that ideal, and how mortality makes that distance feel more acute. “You hear, I think, this sense of going away or being gone,” Bresnick says, “a kind of elegiac departing sorrow which is inevitable in human relations—and certainly if your friend is 100 years old.” Refracted through a scrim of sustained cello, punctuated by soft whirls of lyricism, the result, veiled and rustling, is at once portrait, commemoration, and prospective farewell, “evocative of the mystery of departure,” Bresnick says. Even the most vibrant life is, after all, finite.

Bob HandelmanAt a rehearsal in Yale’s Sprague Hall, Parisot conducts the Yale Cellos—the extraordinary student cello orchestra that he founded and directed until mid-2018. View full imageParisot himself showed little interest in considering such matters. After reaching the century mark, he was still disinclined to sit still. His enforced convalescence, if anything, accented his natural restlessness. Life and work rarely move in straight lines, anyway. That, too, found artistic expression, in Parisot’s undulating, unpredictable paintings. He took up the brush in the late 1940s, soon after arriving in the United States, at a time when his career was promising but still largely prospective, and continued to pursue the craft across the decades, searching, evolving. Hovering between abstract and figurative, sometimes sharply angular and sometimes loose and shaggy, his style was viscerally exuberant: bright, bold whorls, vectors, and crosshatching, brought into harmony by force of personality. The paintings, perhaps, echoed the risk and reward of a musical life. “Being a musician,” Parisot said, “it’s like”—and, again speaking through his hands, he outlined a series of waves. “Sometimes there’s a big wave, sometimes a little wave. It’s always up and down.” Given the man, one might also have added: always rolling forward. He was not prone to living in the past; even retirement only seemed to make him keen to turn another page. Parisot impatiently anticipated his recuperation—“so I can face the world,” he pronounced. “But in the meantime, I sit here, I enjoy my house, and I think.” What was he thinking about? “The future.”

|

|

2 comments

-

McKim Symington, 5:44pm February 26 2019 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

David R Moran, 12:56am March 14 2019 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.As a small boy, I remember Parisot performing at the Sunday Candle Light performances at the Congregational Church in Wilton, Connecticut. Amazing!

How completely strange to read a fascinating and detailed profile of Parisot with no mention, by either him or the author, of his crucial role in the Yale Quartet from the later 1960s - early 1970s and their gold standard late Beethoven cycle.

His playing was not perfect --- the opening of the Op 132 Alla marcia is jarringly sour --- but elsewhere his energy and musicality and directness fully matched the others', and even today it remains a rendition that easily holds its own among the numerous 'very best'.