loading

loading

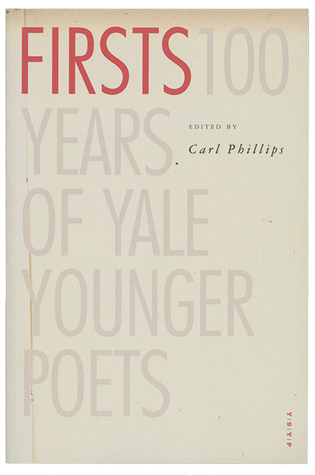

Arts & CultureA century of poetsA new anthology celebrates the Yale Younger Poets Jesse Zuba ’08PhD is an associate professor of English at Delaware State University and author of The First Book: Twentieth-Century Poetic Careers in America.  Winners of the Yale Younger Poets award, celebrating its centennial this year, have included Adrienne Rich, John Hollander, and Margaret Walker; author Carl Phillips, who has judged the prize since 2011, edited the book “Firsts” to commemorate the anniversary. View full image“Who do you want to hear from more than anybody in the world?” James Dickey asked Jody Gladding in 1992 when he called to tell her she’d won the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition. Dickey, a poet and the author of Deliverance, had served as judge of the series for long enough to know what her answer would be. In 2014, Ansel Elkins “did a crazy dance” when she found out that she had won. When Yanyi won in 2018, he declared, “This news will change my life.” Duy Doan, in 2017, simply began to weep; judge Carl Phillips told him, wryly, “You can cry a little, but don’t be sad.” The nation’s oldest annual literary award, now celebrating its centennial, didn’t always carry enough prestige to prompt reactions like these. Its stature took time to build. Conceived in 1919 by Clarence Day ’96, the series was intended to promote “such verse as seems to give fairest promise for the future of American poetry.” Poets who had never previously produced a book would submit their work, and the winner’s poems would be published by the Yale University Press. Judging by their influence on later generations, the first debuts in the series fell short (though some of their authors, such as John Farrar of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, would go on to prominent careers). It was not until 1933, when the Press recruited Stephen Vincent Benét ’19, ’20MA, to judge the series, that its reputation began to grow. Benét worked his connections to search for new talent, and his efforts bore fruit immediately. In 1935, he selected Muriel Rukeyser’s Theory of Flight—the first book in the series that still stands up today. Margaret Walker’s For My People, Benét’s choice in 1942, has never been out of print. Though all of the judges after Benét have made notable selections, it is on W. H. Auden’s tenure that the prestige of the series depends. He was already a major literary figure when he took over the role in 1946, and his name ensured that the series would command attention. The start of his tenure was not auspicious, however. He grumbled about writing introductions, and his first selections were so inaccessible that the Press looked into replacing him. But Auden stayed on as editor, and his choices of the 1950s—Adrienne Rich, W. S. Merwin, John Ashbery, James Wright, and John Hollander—attest to an astonishing ability to recognize talent. Ashbery’s Some Trees was so difficult that it produced angry reactions at the Press, and even Auden felt distaste for its Rimbaud-inspired surrealism; yet he gave the prize to the right poet. Over time, the Yale prize inspired other first-book awards, but it remained debut poets’ most coveted target. Sylvia Plath wrote in her journal of staying up at night thinking “about sending my book to the Yales again.” In the 1960s, Dudley Fitts continued Auden’s success; his first selection, Alan Dugan’s Poems, won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. He was the last of the judges who did not have an international reputation. Stanley Kunitz was followed by Richard Hugo, who was followed by James Merrill, fresh from publishing The Changing Light at Sandover. Then came Dickey, who was followed by Merwin, the first judge who had himself won the Yale prize. In 2003, Louise Glück became the first woman to judge the contest, and in 2011 Carl Phillips the first person of color. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the series. It seems fitting that its latest published volume, Yanyi’s The Year of Blue Water, takes Robert Hass—winner of the 1972 contest—as an explicit point of departure. Blue Water meditates on a sense of self defined both by a stable identity and by change, much like the tradition of which the volume is a part. Sustaining high standards while also evolving under a variety of distinguished judges, the series might be described as Yanyi describes himself: “I am worth the work of transformations.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|