loading

loading

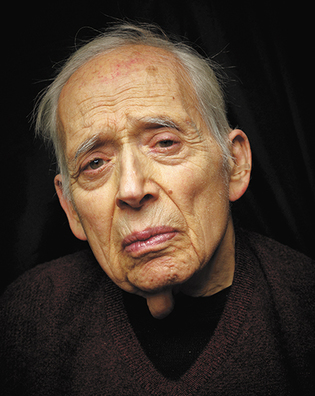

featuresInimitableHarold Bloom, 1930-2019  Rick Wenner/ReduxHarold Bloom, seen here in a photo taken at his home in 2017, taught at Yale for 64 years. View full imageHow to describe Harold Bloom? Towering literary scholar, curmudgeonly critic, astonishing mnemonist, endlessly welcoming host, oracular speaker, and, yes, a man who addressed nearly everyone as “dear.” But all that doesn’t begin to cover everything he was and did. It’s been said before: Bloom was sui generis. He was born on July 11, 1930, in New York City, to a devout Orthodox Jewish family. His first language was Yiddish; at six he began speaking English. After earning a Cornell BA, he came to Yale as a graduate student, took his PhD in 1955, and stayed. He married Jeanne Gould in 1958—she was his mainstay—and they had two children, Daniel and David. Bloom would receive both a MacArthur Fellowship and Yale’s highest academic honor, a Sterling Professorship. Unusually, his professorship wasn’t in English literature, but the Humanities. He hadn’t gotten along with the English department, so he asked for and received a place in a “department” of one. Given the force of some of his criticisms, one can understand why he might not have fit in everywhere. In a 2011 interview on the radio station KCRW, Bloom said Shakespeare was the greatest writer in English—and then added, “I’ve now reached a point where I’ve totally infuriated . . . the horrible Shakespeare establishment, all these dry-as-dust moldy thick scholars.” In his 1994 book The Western Canon, he roundly denounced “the recent politics of multiculturalism” and its “rhetoric suitable for an occupied country.” (Bloom did admire many writers of color and women writers.) And he was very publicly accused by Naomi Wolf ’84 of putting his hand on her thigh when she was his student and they were alone. He denied it. But toward his many students, his friends, and the guests who visited his and Jeanne’s home, Bloom dispensed welcome and warmth, in his inimitably chivalric manner. (Someone who holds virtually all great English literature in their head might reasonably lose the ability for chitchat.) To anyone who knew how much he loved teaching, it’s no surprise that he taught his last class just four days before his death on October 14, 2019. After Bloom died, Columbia professor Andrew Solomon ’85 wrote in the Washington Post: “He may well have been the greatest American literary critic of the past half-century. He was also the best teacher I ever knew: visionary, generous of spirit, and willing to place his students’ strivings on the same level as his own insights. He saw us with the encompassing vision that had rendered him heroic.”—Kathrin Day Lassila ’81, Editor _________________________________________ What follow are ten remembrances of Harold Bloom by colleagues, friends, and former students. Harold Bloom left a lasting impression on three generations of students. He could impart a strong feeling for literature, and especially for English poetry, with a range of mind and a dramatic sense like no one else’s; and he did it by quoting and interpreting. Once you heard him recite and comment on one of his favorite passages, you were bound to think hard (for some time afterward) about the qualities that made it special. From the start of his career, he had shown a prodigious energy for writing and editing; and he became a major contributor to the critical literature on Shelley, Blake, Yeats, Stevens, and Shakespeare. But I think what mattered to him most was teaching, and he kept on teaching right to the end. He was a generous colleague, without a trace of pomp or officious solemnity. He would always rather encourage than mark and measure.

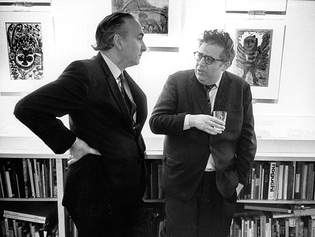

Bloom was wearing a stretched-out orange sweater, and he had begun reading from the moving Conclusion to Walter Pater’s The Renaissance. While continuing to recite (he knew this, like all texts, by heart), Bloom began to remove the sweater. But it got stuck as it passed over his head, so we could hear oracular utterances about life’s irredeemable evanescence continue to come from out of a gyrating mass of wool, until, the garment subdued at last, Bloom pronounced: “That is the most profound thing that was ever written.” Yeats and Stevens remain among my most treasured writers, and they remain, for me, wisdom writers as much as poets. This is a direct debt I bear to Bloom, but the point is a larger one. It’s hard to feel the power of literary works all by ourselves. We need teachers to show us how to love them, how to invest them with the energies of our experience until the text can speak words for us we could not find on our own.  John Sotomayor/The New York Times/ReduxBloom (right), seen here with Oxford University Press editor John Ward at a 1974 event in New York, won widespread academic acclaim for his 1973 book The Anxiety of Influence. View full imageIt is as a teacher that I have most felt the warmth of Harold’s presence in me, and I have felt it every single time I step into a classroom. The inexpressible power, both serious and joyous, that I’ve experienced when gathering with students, brooding with them over a wondrous stanza, a magnificent text, a momentous thought: this has been a blessing that I’ve traced directly to Harold’s example, ever since my earliest days as a TA for a Yale Shakespeare course in 1979. It is what moved me this year to step down as Haverford College president so that I could return to the classroom, which still resonates with Harold’s sense of sacred purpose, guided by his ear for exceptional feeling conveyed with exquisite precision, by his remarkable blend of fearlessness and receptivity, and by his distinctive commitment to literature as an irreplaceable modality of human consciousness and possibility.

He was hungrier for poetry than anyone I have ever encountered. Once, when my wife and I were over at the house on Linden Street—just after he’d returned from a long stay at rehab following an illness—we were sitting in the living room and talking when Harold’s eyes shifted a little to the right of, and just above, my shoulder while I was midsentence. He’d spotted the mailman coming up the path to the front door, and interrupted me: “Peter, could you get the mail?” as we heard the storm door opening and the bundles hitting the floor. I brought them to him. He began ripping into envelope after envelope with his teeth, clutching his cane, and ignoring us entirely. “Harold, expecting something important?” I asked him. Without looking up, and in total seriousness, he answered: “Maybe someone has sent me a great poem.” Most writers I know run the other way when other people’s poems draw near; there was the great Bloom, at 81 or so, just back from a hospital stay, panting after them like a golden retriever.

The heart of Jeanne and Harold’s world and home lives at this table. Never have I walked into the dining room when there weren’t seated and talking at the table at least one or two other people, and often many more—in addition to Harold, in

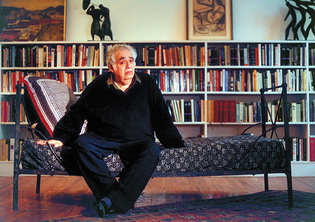

Ted Thai/The Life Picture Collection via Getty ImagesIn 1994, when this photo was taken, Bloom’s book The Western Canon—which the New York Times calls his magnum opus—was published. View full imageWhat sticks in my memory from graduate seminars with Harold are rather plain things. He would usually be at the head of the table when we arrived, sitting and thinking, as if already running thoughts for the session through his head, as if any one seminar were part of a much larger and older conversation. The most vivid memories are simply of his reading to us lines of poetry and asking questions, asking us to listen for curious or hidden things in the words. He would recite something from Hart Crane or Wallace Stevens, and then say about a line, “That is such a strange phrase, what do you make of it?”

Bloom taught me, and taught all his students, how the stakes of poetry are the stakes of living, that poetry matters because it is where we encounter other people at their least guarded, that poetry is the imagination’s way of helping us through the world. I should add a word about Harold Bloom personally. He was a larger-than-life figure, always dramatic, but always with a little wink of humor at his own expense. He was passionate, mercurial, and always magnetic and fascinating. He was also very intellectually and emotionally generous, especially to students at the beginning of their intellectual careers, as I was when I studied American Poetry with him. He had an extremely strong personality. But unlike many strong personalities he never used that strength to make other people feel small. He had a self like Whitman’s; like Whitman he was large and contained multitudes, but like Whitman he also was always opening the door to the “you,” always inviting one to a life of inner equality. You did not look at him, but at the things he looked at, at “Night, sleep, death, and the stars.”

Bloom wrote and edited more than 40 books in his career. View full imageFrom the beginning of the first class, it was clear that it would be unlike any other. Nervously, we filed into the brown-shingled house on Cottage Street, trying to squeeze onto the couches without knocking over Harold Bloom’s small menagerie of stuffed animals. He was already ensconced in his vast armchair, with several volumes of poetry, a sippy cup full of a milky liquid, and a protein bar within reach. There were tea and cookies on the coffee table—he insisted we partake. Always in character, Professor Bloom had assigned reading before the class even started, a selection of Yeats. I was sure I had misread the email at first—surely no course entitled Poetic Influence from Shakespeare to Keats would begin with Yeats? But no—as he would shortly explain to us, he planned to undertake the yearlong syllabus backwards, beginning at the end of the spring syllabus. The class opened with “The Wild Swans at Coole.” The final lines, Bloom revealed, with what we would soon recognize as characteristic dramatic flair, were not included in the first version of this poem, published in 1917. “Why did he add it?” he asked, scanned the room, and then pounced—on me. I stammered something about the specificity of the first person, but the truth is, I had no idea how to answer such a question. I felt like Bloom was asking me to step straight through the surface of the poem and read it from the inside out. This, I learned, was Bloom’s modus operandi. He gave deep rather than close readings, plunging into the sinews of a text rather than dwelling on its surface, but he could also home in on a choice of word or turn of phrase, tracing its origins through Shakespeare, Milton, Shelley, Keats, and so forth. His ability to intuit these connections relied upon his prodigious memory. His reflections on the texts at hand frequently veered into the personal—after a particularly thunderous recitation of Sailing to Byzantium, he told his spellbound class that when his many ailments kept him up at night he liked to recite that very poem to himself to stave off loneliness. Needless to say, it’s hard to imagine how a poem beginning “This is no country for old men” could have soothed him at such a time.

At the head of the oval table in the dining room which was the center of the house, with his wife Jeanne sitting across from him, while the phone rang and people came and went, Harold sat, piles of books balanced on one side, medicine bottles on the other, a yellow pad before him, greeting students and friends with Bloomian nicknames. Discussions about politics and literature would rage, parts of poems would be recited from memory, books would be critiqued, literary gossip would be aired, Yale news would be distributed, Cassandra-like cries about the loss of regard for the aesthetic experience would be shared, and there would be joyous arguing, proclaiming, and declaiming. A colossus of poetry, who bestrode its world with fiery intensity, exuberantly knowledgeable, champion of reading, grand explicator of a canon of which he was the zealous expositor, foe to isms, stubborn guardian of aesthetic and cognitive standards, he stood fast for the sublimity that literature and the act of reading it offer.

The comment period has expired.

|

|