Nathan Keay

Images courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

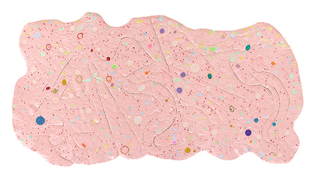

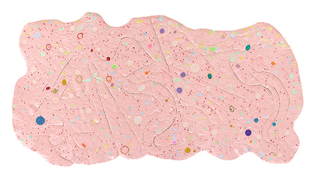

“Carnival: Rio Samba School, Brazil,” by Howardena Pindell, 2018–2019

View full image

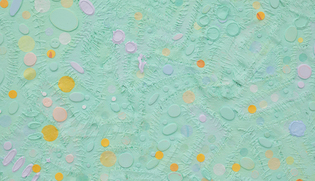

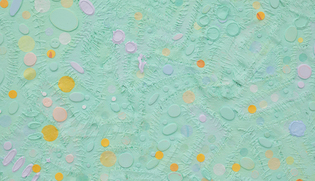

Images courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

“Songlines: Labyrinth (Versailles)” by Howardena Pindell, 2017.

View full image

Howardena Pindell

Artist

By Robin Cembalest ’82

This fall, The Shed in New York opened Rope/Fire/Water, a solo exhibition of work by Howardena Pindell ’67MFA. The show begins in 1974, with a glittering early abstraction, and continues into the 2020s, with several new commissions from the Hudson Yards nonprofit: Columbus and Four Little Girls—mixed-media works chronicling a brutal legacy—and the title piece, a devastating 19-minute video sharing anecdotes, data, and images from lynching and the Civil Rights movement.

Pindell originally proposed this video in the 1970s to A.I.R. Gallery, the woman’s cooperative she cofounded in New York. The rejection was the first of many. “She’s been trying to get this video made for a long time,” says Shed assistant curator Adeze Wilford, who organized the show. “She has been told no a lot.” Pindell’s concept has not changed, Wilford says. But times have: “People are ready for her.”

As a Black woman artist and activist whose goal has been to “deal with American history as it is not told,” Pindell long faced exclusion on many levels. In recent years, she has become recognized as a pioneer and thought leader whose influence goes far beyond the studio. As associate curator in the prints and illustrated books department at the Museum of Modern Art, she was the first African American woman on the curatorial staff. She recently celebrated her 40th year as professor at Stony Brook University, where she teaches painting and conceptual drawing. She is a lifetime activist who has been an outspoken advocate for women and artists of color, calling out systemic racism and double standards.

“She set up a model for what we call a contemporary artist,” says Naomi Beckwith, senior curator at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art. “From early on she was engaged as a curator, writing about other artists, being an active feminist, a political agitator, and very much an educator. This was not expected of artists at that time. The world’s catching up to her.”

Born and raised in Philadelphia, Pindell was a figurative painter when she arrived in New Haven in 1965, after receiving her BFA from Boston University. She was still a figurative painter in 1967, when she moved to New York. By day, she worked at MoMA. By night, she painted. But this was not painting the way Josef Albers and her other Yale professors taught it. Her trademark tool was the hole puncher. She punched holes in manila folders, employed them as stencils, glued the punched-out chads to the canvas, and spray-painted on top. Encrusted with the layered circles, imbued with cat hair, glitter, talcum powder, and perfume, the unstretched, cut, and resewn canvases were like nothing anyone had seen, or smelled.

Pindell’s labor-intensive process evokes women’s work and craft, a direct challenge to mainstream art trends in the 1970s. Her layered, stitched canvases channel Indian patterns, African textiles, Andean weavings, social and political issues, her multicultural ancestry, and her personal and physical traumas. All of this is current practice now, but at the time, Pindell’s dazzling canvases were considered politically irrelevant, even in the Black activist community, where artists were expected to share clear political messages in their work. The director of the Studio Museum in Harlem is said to have told Pindell to “go downtown and show with the white boys.”

In many feminist and alternative spaces, Pindell’s calls for reflection on diversity and inclusion were rebuffed. “I was told I was jealous because I noticed and talked about it,” she recalled in her essay on Free, White, and 21, her notorious 1980 video satirizing the hypocrisy of white feminists. In the 12-minute work, she plays herself, the Artist, recounting personal experiences of anti-Black racism. She also appears in whiteface and blond wig as White Woman, who denies the artist’s experience. “You ungrateful little . . . ,” the woman says. “After all we have done for you.” For many years Pindell had trouble showing the piece in museums. Now it is considered a seminal work of video art.

While she was completing Rope/Fire/Water this summer, events showed why the five-decade-old concept remains so painfully timely. As a coda to the video, she added names of people who had been killed by vigilantes or the police in the last five years. Says Wilford, “It feels like a warning and a rallying cry.”

loading

loading